Andrew McGregor

February 23, 2005

Mauritania, the vast desert refuge of the Arab/Berber Moors in northwest Africa, may seem a distant front in the war on terrorism. Yet the pro-Israel/U.S. policies of its President, Maaouya Ould Taya, have sparked an Islamic revival in this traditionally moderate nation, a country that takes pride in being the world’s first Islamic Republic. Mauritania has experienced no domestic acts of terrorism or known al-Qaeda activity, but the President claims Islamists with foreign connections guided three recent coup attempts. The unexpected outcome of the just-completed trial of 181 alleged insurgents helps shed some light on the nature of the Islamist threat in Mauritania.

Led by 20-year-old Iraqi tanks, a rebel faction of the army smashed into the capital of Nouakchott on June 7, 2003, driving to the presidential palace. The insurgents were led by a secret group of officers who styled themselves as “The Knights of Change”. Heavy fighting continued for three days until a final breakout attempt by the surrounded rebels was defeated. At least 15 people were killed and 68 wounded.

“Knights of Change” Leader Major Salih Ould Hanana

“Knights of Change” Leader Major Salih Ould Hanana

From the beginning, the regime blamed Libya and its close ally Burkina Faso of instigating the rebellion and supplying arms and military equipment, presenting captured weaponry to support its claim. And though the blame was publicly applied elsewhere, the administration quietly closed three important Saudi institutions in Nouakchott. In any case, the President announced that foreign-linked Islamists intent on destroying the achievements of his government were responsible for the fighting. Ould Taya also maintained that two further coup plots were broken up in August and September 2004.

The Trial

Because of security concerns and the large number of suspects, the trial was moved in late 2004 to Wad Naga, a desert military garrison 50 kilometers from the capital. There were numerous charges of torture from the detainees which appeared to be verified by smuggled footage of beaten, starved and chained prisoners aired on satellite TV and the Internet. Medical attention was denied and protests by the prisoners’ families were met with mass arrests. Three prominent Islamists were arrested for distributing the photos.

Coup leaders Major Salih Ould Hanana and Captain Abdul Rahman Ould Mini entered guilty pleas. Hanana used his time in court to deny receiving foreign assistance and to describe the President as “[A] despot who doesn’t respect the laws of the country or international conventions… I wanted to change a rotten and illegal regime by way of a coup, similar to that launched on 12 December 1984 by President Ould Taya.” [1] Islamist rhetoric was noticeably absent from Hanana’s address. Ould Mini cited the tribalism prevailing in the government and the injustices in the army as reasons for his leading role in the “Knights of Change”. [2]

Both Hanana and Ould Mini were given life with hard labor. Even the defense lawyers were surprised by how little evidence was provided for the second and third coup attempts. When the verdict was brought in, the opposition leaders held responsible for these later plots were all acquitted. Prosecutors sought but failed to obtain the death penalty in 17 cases. Over 100 of the accused were released, with most of the rest receiving 18 month sentences.

Mauritania’s New Foreign Policy

Diplomatic relations with Israel were opened in 1999, prompting an angry response from Iran and many Arab nations. The President no longer attends Arab summits and the tightly controlled official press has a noticeable lack of information about Iraq or Palestine. Ould Taya’s shift in alignment from the Arab/Islamic world to the U.S. and Israel has created a wide gulf in Mauritanian society. The French and Arabic speaking Mauritanians feel a natural attachment to France (the former colonial power) and the Arab world. The Islamic opposition warns that allowing Israel to establish a presence in the country is to open the door to Israeli intelligence activities in North Africa. The U.S. and NATO are both interested in developing Mauritania as a cornerstone for anti-terrorism operations in North Africa.

Calls for change have also been fueled by the discovery of large offshore oil reserves. Production is scheduled to start next year at an initial rate of 75,000 barrels per day. While the amount is not large compared to some Arab states, it has life-changing potential for impoverished Mauritanians who survive on an average income of US$1 per day. The leading company in Mauritania’s new offshore oil industry is Australia’s Woodside Petroleum, with major contracts for development awarded to the Halliburton Corporation. The opposition fears that the oil revenues will be swallowed up by a well-entrenched system of government corruption.

The Opposition

The same ethnic, tribal and caste divisions that characterize Mauritanian society fracture the political opposition. Both government and opposition remain dominated by the Bidan, the “White Moors”. Despite the name, paternal descent from Arab/Berber roots is more important in determining status as a “White Moor” than actual skin color. The “Black Moors”, or Haratin, may be understood as black African freedmen who have completely assimilated to Moorish culture and religion. The Bidan are further divided by clans and castes, the warrior and marabout (religious) castes being the most important. The marabouts form the traditional Islamic leadership. Some 30% of the population is composed of non-Moor black African Muslims in the south of the country. Some Bidan are alleged to still keep black Africans as slaves.

Mauritanian democracy is more a matter of form than substance. A Parliament exists, though real power rests with the President. Small and ineffective political parties are allowed to contest elections (when not banned by Presidential decree). The regime has refused to register Islamic political parties and the Ba’ath party has been banned since 1999, though there is a lingering Ba’athist influence in the army’s officer corps as a result of many officers receiving military training in Iraq from 1984 to 1996. Many of the known Ba’athists in the army were dismissed in 2000 amidst the dissatisfaction with Mauritania’s new friendship with Israel. Following the invasion of Iraq in 2003 more Iraqi-trained officers were dismissed and a large number of “Islamists” rounded up.

Islamism is a relatively new phenomenon in the country, which remains heavily influenced by the traditional Sufism of the Tijaniya and Qadiriya orders. Islamic activities are tightly controlled by the Ministry for Islamic Development and Culture and the officially approved mosque leaders can usually be mobilized in support of the government.

Former al-Qaeda Spokesman Abu Hafs al-Mauritani

Former al-Qaeda Spokesman Abu Hafs al-Mauritani

The most notorious of Mauritania’s radical Islamists is a high-ranking al-Qaeda leader, Abu Hafs al-Mauritani (Mahfouz Ould al-Walid). Abu Hafs acts as a spiritual advisor to al-Qaeda, though he has no special following in this regard. He followed Bin Laden from Sudan to Afghanistan where the U.S. believes he played an important role in planning the East African embassy attacks and 9/11. Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz has suggested that Abu Hafs was the prime al-Qaeda advocate for cooperation with Saddam Hussein. In the months after 9/11 Abu Hafs acted as an al-Qaeda spokesman, denying responsibility for the attacks. [3] Abu Hafs was mistakenly reported killed by the U.S. in Afghanistan in January 2002. He is now believed to be in Iran, possibly under detention. [Update, February 22, 2016 – Abu Hafs spent ten years in Iranian prison before being extradited to Mauritania].

Less well known is a relative through marriage, Mohammadou Ould Slahi, a Mauritanian who acted as liaison between the Hamburg cell and Osama bin Laden in planning the 9/11 attacks. Ould Slahi is reported to have made two trips to Afghanistan for al-Qaeda training. In 1999 Ould Slahi was in Montreal, where he is alleged to have helped Ahmad Ressam with the “Millennium Plot” bombing attempt. Arrested by Mauritanian police in 2001, Ould Slahi is now believed held in a special CIA unit at Guantanamo Bay. [Update: February 16, 2016 – After fourteen years, Ould Slahi remains in Guantanamo Bay without charges, where he is reported to have experienced torture, sexual abuse and mock executions].

Conclusion: “The Hanana Effect”

With the trials drawing to a close, the Ould Taya government announced a 400% increase in the minimum wage, bonuses for civil servants and improved living conditions for the military, developments that quickly became known as “the Hanana effect”. The announcements came just as most of Mauritania’s people face severe food shortages as a result of last year’s devastating locust plague.

In the end, neither Ba’athism nor Islamism seem to have been decisive factors in the military rebellion. Within the army and the government Ould Taya is accused of favoring tribesmen from his homeland in the northeast. The inequitable distribution of promotions and poor living conditions for the military undoubtedly had as much to do with the coup as political factors. Some of what is called Islamist (i.e. Salafist) activity is actually the reassertion of the marabout caste in their role as Islamic leaders. The marabouts are alarmed with the radical change in foreign policy of their Islamic state. More locally they have lost control of the Qur’anic schools to the Government but retain close ties with the army and the civilian opposition. The Islamist-Salafist trend remains marginal in Mauritania and certainly does not have the type of influence needed to be mount coups or form a Shari’a based government. No connection between the Islamists and the putschists was established in the trials.

Ould Taya sees an opportunity to solidify his rule through participation in the war on terrorism, even if it means creating Islamist threats and external aggressions where none exist. Hanana and some other rebel officers come from warrior tribes that traditionally work closely with the marabouts. There may be further cooperation between these two castes to restore the customary balance of power within Mauritania. This local reaction to Ould Taya’s tribalism and authoritarianism remains open to exploitation by Salafist extremists but no evidence exists that this process has begun. Growing ties with the U.S. and Israel are isolating the Ould Taya regime, which will increasingly have to rely on the loyalty of the army. Furthermore, Ould Taya may see a U.S. military presence and Israeli security assistance as insurance for the survival of the regime.

This article was originally published in the February 23, 2007 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.

Notes:

1. ‘Proces de OuadNaga: Audience du 23 decembre, 2004′, Nouakchott-Info, www.mapeci.com/700/actualite.htm .

2. ‘Le Capitaine Ould Mini plaide coupable’, Nouakchott-Info, Dec. 25, 2004, www.mapeci.com/701/actualite.htm .

3. ‘Al-Jazeera interviews bin Laden deputee Abu Hafs al-Mauritani: The Relationship between Tanzim al-Qaedah and the Taliban movement’, November 20, 2001 (Broadcast December 11, 2001) www.aljazeera.net/programs/special_interview/articles/2001/12/12-4-1.htm.

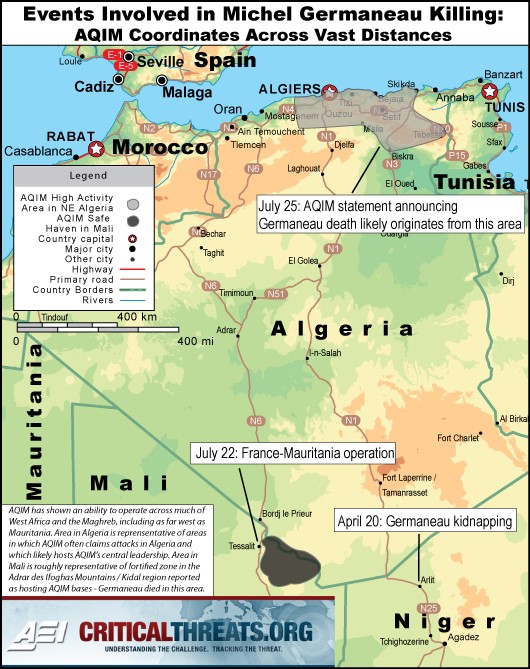

Abd al-Hamid (Hamidu) Abu Zaid, an AQIM commander responsible for a number of kidnappings and for the execution of British tourist Edwin Dyer, is reported to be suspicious that the Tuareg provided the precise information that enabled the joint commando force to locate and kill the six AQIM operatives. Abu Zaid took his revenge by abducting and murdering a Tuareg customs officer named Mirzag Ag al-Housseini, the brother of a senior Malian Army commander, Brahim Ag al-Housseini (El Khabar [Algiers], August 12). No ransom was sought for the captive, who was executed on August 12 (Radio France Internationale, August 13). A soldier abducted at the same time as Mirzag and another abducted civilian were released by AQIM on August 16 (AFP, August 16).

Abd al-Hamid (Hamidu) Abu Zaid, an AQIM commander responsible for a number of kidnappings and for the execution of British tourist Edwin Dyer, is reported to be suspicious that the Tuareg provided the precise information that enabled the joint commando force to locate and kill the six AQIM operatives. Abu Zaid took his revenge by abducting and murdering a Tuareg customs officer named Mirzag Ag al-Housseini, the brother of a senior Malian Army commander, Brahim Ag al-Housseini (El Khabar [Algiers], August 12). No ransom was sought for the captive, who was executed on August 12 (Radio France Internationale, August 13). A soldier abducted at the same time as Mirzag and another abducted civilian were released by AQIM on August 16 (AFP, August 16).