Andrew McGregor

July 15, 2010

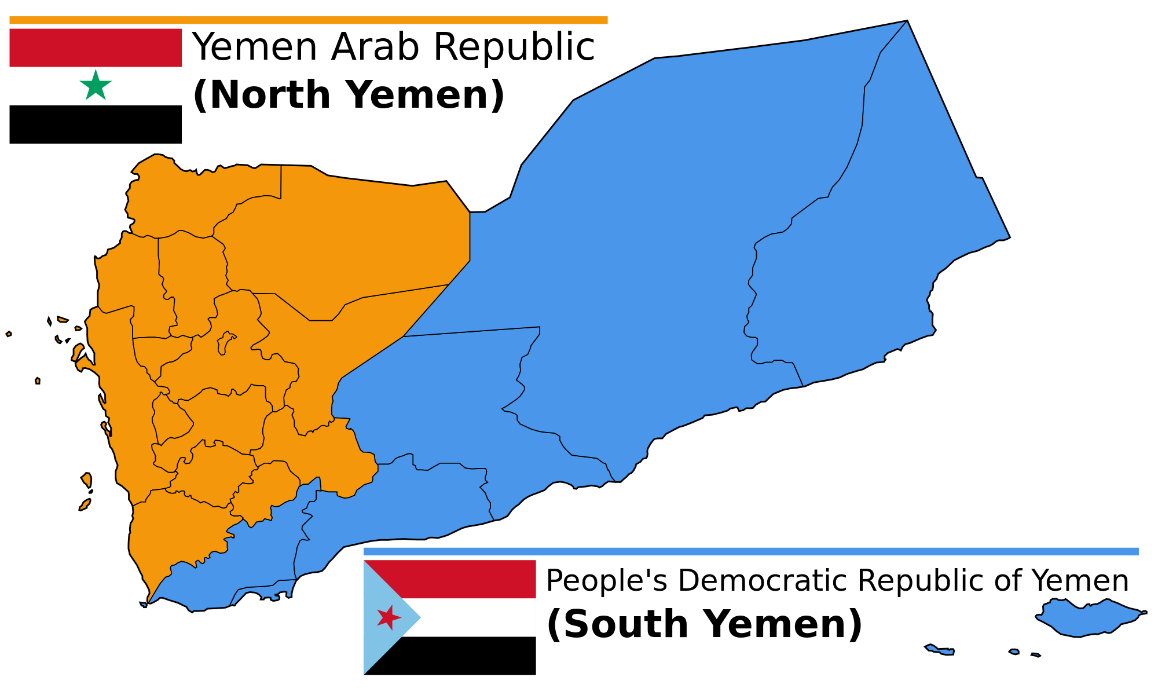

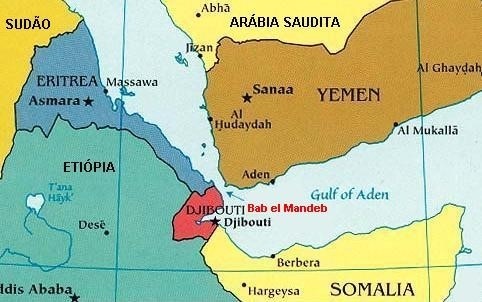

A small governorate of roughly 150,000 people, Ma’rib was once the heart of the great Sabaean civilization of pre-Islamic times, a land made prosperous by the construction of great irrigation works. Its wealth figured in the legends surrounding reputed rulers like Queen Sheba. When the Great Dam of Ma’rib collapsed in the 6th century, many of its people spread across North Africa and the region entered a long decline, enjoying a slight revival with the discovery of oil in the mid-1980s and the construction of a new dam funded by the late ruler of Abu Dhabi, Sheikh Zayed Bin Sultan al-Nahyan. Political violence entered the region, however, and the ruined Awam (Moon) temple of Ma’rib became the scene of an al-Qaeda suicide bombing in 2007 that killed eight Spanish tourists and two Yemenis (France 24, June 7).

Awam Temple in Ma’rib

Awam Temple in Ma’rib

Though Yemen’s reserves of oil (never substantial by Arabian Peninsula standards) are quickly diminishing, al-Marib remains home to vast oil and gas reserves, making it a hub for the regional energy industry that provides 90% of government revenues, with vulnerable pipelines connecting the region to export terminals on the southern coast. These pipelines were cut by attacks 60 times last year (Elaph, June 13).

Like most of Yemen, the population of Ma’rib is largely tribal-based with a certain degree of de-facto independence from the state. Government is as much tolerated as respected. Most notable among the Ma’rib tribes are the Abidah, the Murad, the Jahm, the Jad’an and the Ashraf Ma’rib.

The Killing of Jabir Ali al-Shabwani

On May 24, what appears to have been an American unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) fired a missile at a home in Ma’rib’s Wadi Abieda area (Yemen Post, June 19; Al-Quds al-Arabi, June 27). The home belonged to a wanted al-Qaeda operative, Muhammad Sa’id bin Jardane, who was wounded in the strike but managed to escape. However, the strike did not miss Ma’rib Deputy Governor Jabir al-Shabwani and his four bodyguards, who were all killed. Al-Shabwani had been negotiating Bin Jardane’s surrender for a week and had gone to his farm to finalize the terms (AFP, May 25).

Outraged by what they believed was a plot to kill a notable tribal leader, tribesmen of the Shabwani clan and the larger Abidah tribe began attacks on government facilities and military outposts. Tribesmen destroyed parts of the Ma’rib city center, even attacking the city’s air defense camp (Yemen Observer, May 29). A targeted assassination of a senior military officer carried out in Ma’rib several days later by members of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) further inflamed the region as a military offensive sought revenge.

Al-Qaeda Activity in Ma’rib

According to security authorities, in the last three years al-Qaeda has killed 37 military and government officials in Ma’rib from a list of 40 targets. A new list has allegedly been compiled by the militants (Saba, June 13). AQAP leaders Nasser al-Wuhayshi, Sa’id al-Shihri and Qasim al-Raimi were reported to be in Ma’rib in June. Authorities speculated they were fleeing a government offensive in the Abidah region of Ma’rib (Yemen Observer, June 17). Later there were unconfirmed reports that AQAP leader Ali Sa’id bin Jameel was killed by a military bombardment (Okaz.com, July 4; Saudi Gazette, July 4).

AQAP is believed responsible for the June 5 ambush and killing in Ma’rib of General Muhammad Salih al-Sha’if (commander of the 315 Brigade), though an AQAP statement denied responsibility, saying the murder was a government ploy to legitimize attacks on the local tribes (Marebpress.net; June 5; Yemen Post, June 19). Vowing revenge, government forces concentrated their search for suspects in the Abidah region of Ma’rib, focusing on Hassan Aridan and 28-year-old Hasan Abdullah Saleh al-Aqili, described as an al-Qaeda commmander in Ma’rib.

AQAP is believed responsible for the June 5 ambush and killing in Ma’rib of General Muhammad Salih al-Sha’if (commander of the 315 Brigade), though an AQAP statement denied responsibility, saying the murder was a government ploy to legitimize attacks on the local tribes (Marebpress.net; June 5; Yemen Post, June 19). Vowing revenge, government forces concentrated their search for suspects in the Abidah region of Ma’rib, focusing on Hassan Aridan and 28-year-old Hasan Abdullah Saleh al-Aqili, described as an al-Qaeda commmander in Ma’rib.

Twelve security men and 11 tribesmen were injured during a June 9 shootout with Abidah tribesmen at al-Aqili’s home in Ma’rib’s al-Madina district, but the militant and his followers escaped (Yemen Observer, June 9). The fighting began after soldiers destroyed the homes of several al-Qaeda suspects and then began shelling the entire area, according to a local official (Xinhua, June 9).

Resorting to Traditional Mediation

At this point both sides resorted to the traditional Yemeni mediation methods that forever keep Yemen at the brink of disaster rather than falling off the precipice. Unable to allow Ma’rib’s energy industry to slip from its control, Yemeni authorities issued an apology for the airstrike and President Saleh formed a special president’s committee including leaders of the Abidah tribe to investigate (al-Hayat, June 9).

Eventually the Yemeni press published a statement from the late deputy governor’s father, Shaykh Naji al-Shabwani, apologizing for the Abidah tribe’s “moment of anger” following his son’s “assassination.” The elder Shabwani was invited to a personal meeting with the president and agreed to accept tribal mediation, thus helping defuse open rebellion in the region over the killing of his son. Addressing the belief in the Abidah tribe that Jabir Ali al-Shabwani was the victim of a plot at the highest levels, the shaykh added, “If the president was behind the killing of my son, then he should confess and I, on my part, will forgive him” (al-Masdar, June 6; al-Quds al-Arabi, May 31). Confessions, however, were not forthcoming, and there were reports that other Abidah shaykhs had rejected the arbitration. Even as progress was made on defusing this issue the government’s broad hunt for the killers of General Muhammad Salih was intensifying the violence in the region.

A Ma’rib arbitration committee decided to take sworn oaths from Yemen’s leaders testifying that they had no prior knowledge of the airstrike that killed al-Shabwani. The state additionally agreed to pay blood money in the amount of one billion riyals (approximately 4.5 million dollars) (Al-Quds al-Arabi, June 27). The procedure effectively removed all responsibility from the Yemen government and left the United States solely to blame for the attack. Locally this also had the effect of relieving Yemeni officials of any personal responsibility, with all the consequences of tribal vendetta that would follow (al-Quds al-Arabi, May 31).

The Counterterrorist Offensive Meets Tribal Resistance

A leading member of the local tribal structure, Alawi al-Basha bin Zaba, secretary-general of the Alliance Council of the Ma’rib and al-Jawf tribes (al-Jawf is a neighboring governorate) told a London-based Saudi daily that the military operations in Ma’rib and their resulting collateral damage threatened to turn Ma’rib into “another Sa’dah,” referring to the simmering rebellion in north Yemen that has posed one of the Yemeni state’s most serious challenges. The operations in Ma’rib “will pull the tribes into confrontation with the state. We have warned of such a situation and said that it must be handled in a completely different way. ” Of particular offense was the practice of demolishing the homes of al-Qaeda suspects by firing mortars and Katyusha rockets from a range of some kilometers, inevitably destroying the homes of people with no relation to the militants. Bin Zaba saw a darker purpose behind such tactics; “Some officials might be seeking to push the tribes towards allying with al-Qaeda… Some officials and shaykhs are benefiting from keeping the situation as is,” he said (Elaph, June 13). The tribal leader suggests official reports regarding the presence of al-Qaeda in Ma’rib are exaggerated and designed to increase foreign aid to the state.

Fighting threatened to grow out of control as Yemeni armor began to roll into Ma’rib and tribal allies of the Abidah and the Shabwani clan began to pour into the region from neighboring governorates. Attacks were made against the local Republican Palace, military outposts and power stations. Pylons carrying electric power to Sana’a were brought down and al-Jad’an tribesmen blocked the road between Sana’a and Ma’rib. Gas pipelines were destroyed and technicians prevented from making repairs. When planes of the Yemeni Air Force began flying over the region the Abidah tribesmen responded by firing antiaircraft weapons. The Alliance Council of the Ma’rib and al-Jawf tribes described the government offensive as “terrorist acts” and warned that if political intervention was not forthcoming, “the tribes will abandon their responsibilities and allow al-Qaeda to take control of Ma’rib Governorate” (Ma’rib Press, June 11).

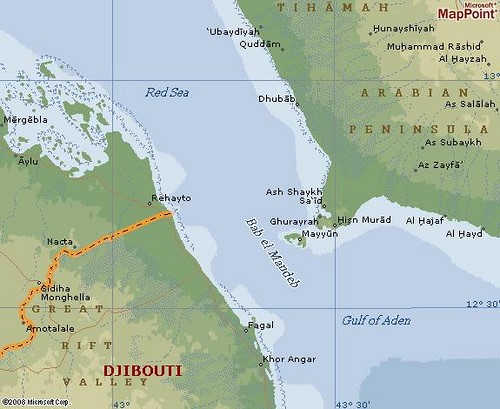

A June 12 meeting between shaykhs of the Abida tribe and Interior Minister Major General Mutahar Rashad al-Masri produced an agreement in which the tribe vowed to stop harboring al-Qaeda suspects, condemned sabotage and agreed to dismantle roadblocks and allow repairs to the pipeline (AFP, June 13). Al-Qaeda had different plans, however. In mid-June, AQAP released a statement in response to what it described as attacks on “women, children and brothers” in the Wadi Abidah region of Ma’rib. The group appealed to the shaykhs of Abidah and the shaykhs of Ma’rib to distance themselves from the “Crusader campaign” and President Ali Abdullah Saleh stated, “With permission from God, [we will] set the ground alight under the feet of the tyrant infidels from the regime of Ali [Abdullah] Saleh and his aides – the agents of America” (al-Jazeera, June 19). There has been speculation that the devastating June 19 AQAP attack on the Aden offices of the Political Security Organization (PSO) was intended as revenge for the assault on the Abidah region and was part of an effort to ingratiate themselves with tribal leaders who had agreed to expel al-Qaeda elements from their territories (Al-Ahali, June 22).

Destroying Ma’rib’s Main Pipeline

On June 12, a bulldozer was used to destroy the main pipeline carrying oil to the Hodeida governorate port of Ras Issa, the third attack on the pipeline in less than a month. Ministry of the Interior sources said the attack was the work of the Hatik sub-tribe of the Abidah, angered by the military offensive. Ministry of Defense sources claimed that the attack had actually been the work of Saudi AQAP deputy leader Sa’id al-Shihri (26sep.net, June 14; Okaz, June 16; Yemen Post, June 28). Al-Hatik leaders denied any participation in the attempt to break the pipeline (al-Taghyir [Sana’a], June 17).

Local sources told a pan-Arab daily that those who attacked the pipeline were tribesmen with no ties to al-Qaeda seeking revenge for an entire family that was killed by army shelling during operations in the Abidah region. The tribesmen were also angered by an attempt to arrest Shaykh Nasir Qammad bin Durham, who was accused of harboring al-Qaeda operatives. The shaykh evaded security authorities but his home was destroyed by artillery. The bulldozer attack on the pipeline was said to have created a huge fire with a smoke column that could be seen 40 km away (al-Hayat, June 13).

More violence broke out in Ma’rib as tribes began fighting over control of the local oil fields. Government forces did not intervene in recent clashes between the Abidah and the Bal-Harith that killed 18 during fighting over an oil field near the border with Shabwa governorate (Yemen Post, June 24; al-Tagheer, June 24).

Conclusion

A recent study of the political role of Yemen’s tribes stated that the often abrasive relations between the tribes and central government had been tempered by President Saleh’s attempts to improve the relationship. The tribes now dominate both parliament and the Shura Council, resulting in some tribal conventions being integrated into national legislation. However, the hereditary nature of tribal authority and the dominance of tribal chiefs have led to the exclusion of tribesmen from political involvement. An estimated 85% of Yemenis belong to tribes, most of which are well-armed. [1]

Despite evidence to the contrary, Ma’rib Governor Naji Bin Ali al-Zaidi prefers to maintain that al-Qaeda members in Ma’rib are not natives of the area, but are rather “strangers who are exploiting the hospitality of the Ma’rib people to hide and plan for their terrorist operations.” The governor points to the wild terrain and nomadic nature of the local people as draws for a terrorist group seeking safe havens. Al-Zaidi warns that al-Qaeda “are targeting the whole world through our province, because Yemen, several Arab and foreign countries all have interests in this province” (Yemen Observer, March 9). Regardless of the governor’s claims, there appears to be continued sympathy for local al-Qaeda members in the region. Recently two AQAP members wanted for attacks on military and security forces, Mansur Saleh Dalil (a.k.a. Salel Salim Dalil) and Mubarak al-Shabwani, surrendered to authorities in Ma’rib. Attacks on security checkpoints quickly followed the death penalties handed down to the men on July 7 (Saba, June 15, July 11; Yemen Post, June 15).

By accommodating American requests for direct strikes against al-Qaeda suspects in Yemen, government authorities are left to deal with consequences that can quickly spin out of control in a highly volatile environment. There are estimates that the cost of lost oil revenues, repairs to the power supply and compensation to the tribes in Ma’rib will exceed the annual amount of U.S. aid to Yemen. The military response to the assassination of senior officers seemed to invoke the tribal principle of collective responsibility, with the counterterrorist offensive in Ma’rib making little differentiation between the guilty and the innocent. Coming at the same time as the airstrike that killed a noted Abidah leader, the rapid escalation in violence and its potential to spill into neighboring governorates provided a warning that some areas of Yemen are perilously close to breaking with the government and accepting an al-Qaeda presence. The heavy-handed military tactics that helped break the Houthi rebellion (at least temporarily) during “Operation Scorched Earth” will not necessarily work in other regions. Traditional mediation efforts appear to have subdued the violence, but the risk remains that in the current environment apologies, compensation and mediation may not be effective next time, particularly if the tribes are convinced to accept al-Qaeda operatives (their relatives and fellow tribesmen) as their protectors and avengers against a state they perceive as working for foreign interests.

Note

1. See Adel al-Sharbaji et al., Palace and the Divan, the Political Role of Tribes in Yemen, Observatory for Human Rights/International Development Research Center. For a summary, see Yemen Times Online, April 7, 2010.

This article first appeared in the July 15, 2010 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor