Andrew McGregor

May 10, 2007

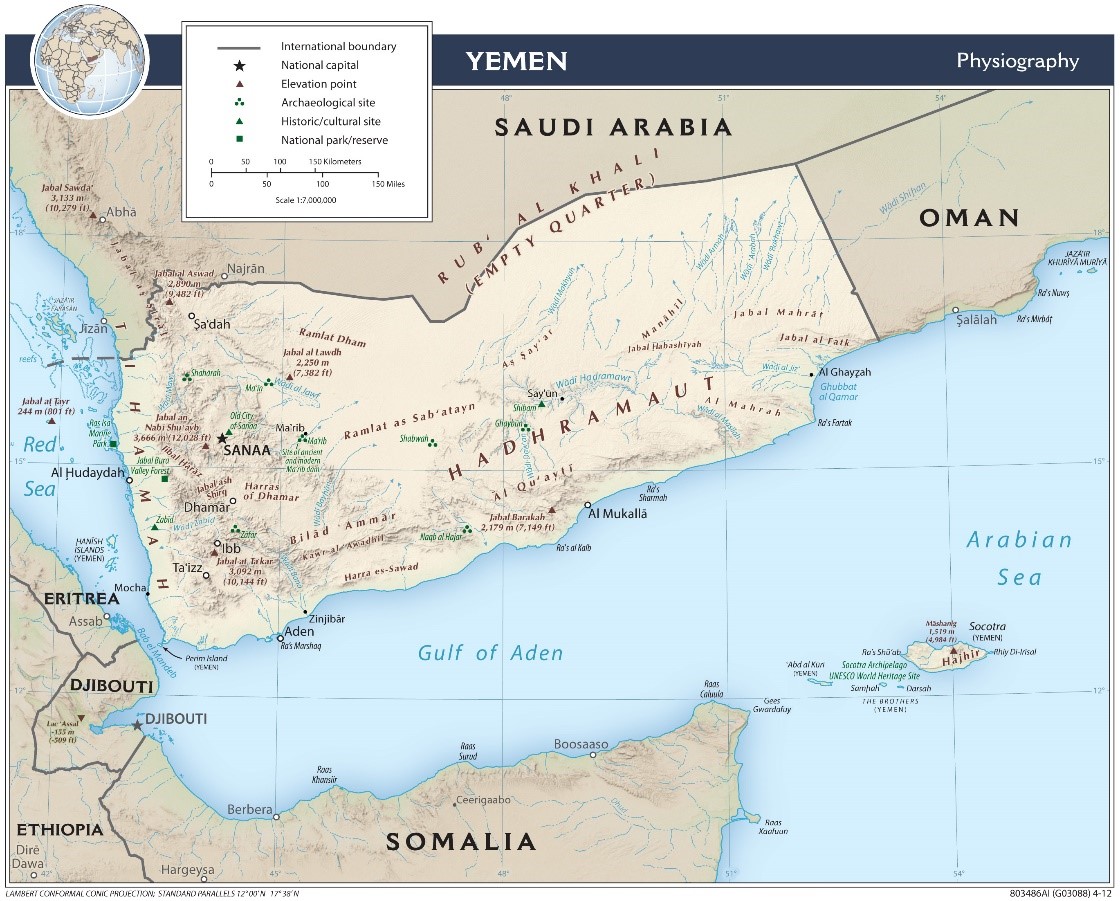

Following the introduction of a new two-year plan to eliminate religious-based political extremism in Yemen, President Ali Abdullah Saleh made an official visit to Washington from April 30 to May 3. While in the United States, President Saleh discussed security and counter-terrorism efforts with President Bush, FBI Director Robert Mueller, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, CIA Director Michael Hayden and members of the House of Representatives Intelligence Committee. The visit marked an enormous change in U.S.-Yemeni relations since the dangerous days following the September 11 attacks, when a U.S. attack on Yemen seemed imminent. At the conclusion of his stay, President Saleh thanked the United States for its support of Yemen’s counter-terrorism efforts, while President Bush spoke of Yemen’s continuing cooperation in bringing “radicals and murderers” to justice. Nevertheless, while the sometimes-tempestuous U.S.-Yemeni alliance carries on, there are serious differences between the Yemeni and U.S. approaches to counter-terrorism.

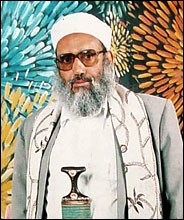

Judge Hamoud Abdulhamid al-Hitar

Judge Hamoud Abdulhamid al-Hitar

Reforming Terrorists with Islam

The most unusual aspect of Yemen’s counter-terrorist efforts is a broad effort to reform religious extremism (both Shiite and Sunni) and replace it with a moderate approach to Islam. This task (rooted in traditional Yemeni methods of conflict resolution) has been handed to Yemen’s recently appointed minister for Endowments and Religious Guidance, Judge Hamoud Abdulhamid al-Hitar, who states, “The strategy will be an important factor in treating their mistaken ideas” (Yemen Observer, April 30). As the leader of Yemen’s Dialogue Committee, al-Hitar developed a policy of confronting incarcerated militants in debates designed to expose their misinterpretations of Islamic doctrine and challenge the legitimacy of al-Qaeda-style jihadism. Using “mutual respect” as a basis for the discussions, al-Hitar points to numerous successes in reforming the views of extremist prisoners, some of whom later provided the security apparatus with important intelligence. Hundreds of terrorism suspects have passed through the program. Recidivism is untracked, however, and there are reports that some of those released went to Iraq to fight U.S.-led coalition forces. The list of graduates is closely guarded, and ex-prisoners are warned not to discuss their participation in the dialogues, thus allowing a degree of deniability should graduates return to terrorism.

Within Yemen, al-Hitar is widely believed to be a member of the feared Political Security Organization (PSO). When 23 terrorism convicts escaped from a PSO prison in the national capital of Sanaa last year, their tunnel emerged in al-Hitar’s mosque. The mass escape was clearly assisted by some PSO agents. The fact that the escapees included several convicted of bombing the USS Cole placed a severe strain on U.S.-Yemen relations.

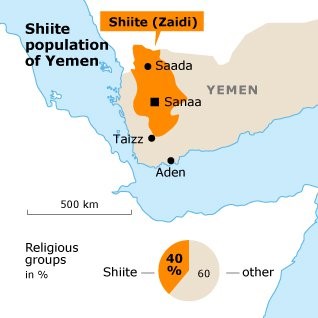

For two years, the Ministry of Endowments and Religious Guidance has kept a close watch on unlicensed Quranic schools suspected of promoting political violence, although none have been closed so far. A corps of “religious guides” (both men and women) has been tasked with promoting “the noble values of Islam” and to establish the principles of moderation and tolerance in areas where the government fears extremism is feeding on a lack of religious knowledge (Saba News Agency, April 25). Saleh has challenged the country’s religious scholars and preachers to “clarify the facts” of Islam for the Muslim community, especially in rebellious Sa’dah province, where preachers have a “religious, moral and national duty” to eradicate sedition.

Steps Toward Disarmament

On April 24, Yemen’s cabinet took the unusual measure of ordering the closure of Yemen’s many arms shops and markets, finally acknowledging that the proliferation of weapons and their common use to resolve all types of disputes are continuing barriers to much-needed foreign investment. Heavy weapons are to be confiscated, while possession and sales of sidearms and assault rifles will be subject to licenses and registration. With some 50-60 million weapons in circulation in a country of 21 million people, the cabinet’s order represents only a first step toward changing Yemen’s ubiquitous arms culture. At the moment, there are 18 major arms markets and several hundred gun-shops in Yemen. Some shops will be allowed to reopen for the sale of personal arms under government control (IRIN, April 26). Yemen continues to be an important regional transit point for arms shipments of all types, a lucrative trade that benefits leading members of the regime.

Legislation to regulate the possession of arms continues to be opposed by a number of members of parliament who, like most of their constituents, regard holding one or more weapons as a traditional right. Some of the larger tribes possess stockpiles of heavy weapons that they will be reluctant to part with, given the 22 tribal clashes recorded last year alone. The tribes also regard their weaponry as a means of protecting themselves from government malfeasance.

Reforming the Security Apparatus

Apart from the military, Yemen’s security is handled by three civilian agencies, at least two of which are believed to include Salafi and Baathist sympathizers at the highest levels. Most important of these is the PSO. A number of PSO officials have been dismissed in the last few years in an attempt to eliminate corruption and Islamist sympathizers from the organization as it is reshaped to take the lead in Yemen’s counter-terrorism effort. The PSO reports directly to the president and its upper ranks are composed exclusively of former army officers. The Ministry of the Interior runs the Central Security Organization (CSO), a paramilitary force of 50,000 men, equipped with light weapons and armored personnel carriers. The smaller National Security Bureau (NSB), founded in 2002, reports directly to the president as well. The NSB may be designed to be in competition with the PSO. The United States currently offers counter-terrorist training to members of Yemen’s security forces and is involved in helping build a new national Coast Guard (a project that also includes contributions from the United Kingdom and Australia).

The CSO’s elite Counter-Terrorism Unit (CTU) is trained jointly by the United States and the United Kingdom. As a relatively new organization formed in 2003, the CTU is expected to apply innovative strategies to counter-terrorism work, while avoiding the corruption ingrained in more senior security groups. The Interior Ministry is also engaged in a campaign to decrease the size of both official and unofficial corps of bodyguards employed by public figures in Yemen. Some groups of bodyguards now approach the level of private militias, enforcing the will of local sheikhs and tribal leaders (Yemen Observer, April 24).

Arbitrary arrests and extended detentions without charge or trial continue to be preferred methods of the security services. The PSO, CSO and many tribal sheikhs operate their own extra-judicial detention centers. Relatives of militants are routinely imprisoned to put pressure on wanted individuals to surrender. At a recent judicial symposium, it was suggested that there are as many as 4,000 innocent citizens being held in the prisons of the security services (Yemen Observer, April 28). Regular use of torture in Yemen’s prisons and other judicial abuses have been documented in the U.S. Department of State’s annual report on human rights (Yemen Times, March 14).

The ongoing rebellion in Sa’dah province has the advantage, at least, of keeping the army busy while Saleh attempts to repair relations with Washington. Many in the officer corps were trained in Baathist Iraq and deeply oppose the U.S.-led intervention there. Dissatisfaction in the ranks has not yet become disloyalty, however, and Saleh has placed a number of family members in crucial command roles to ensure that it stays that way. These include his son Ahmad (a possible presidential successor and presently commander of the Republican Guard and the Special Forces), his brother Ali Saleh al-Ahmar (commander of the Air Force) and half-brother Ali Mohsin al-Ahmar (commander of the northwest region and a long-time Salafi sympathizer). Two of the president’s nephews serve as commanders of the CSO and the NSB.

U.S. diplomats in Yemen have frequently been targeted by Salafi extremists, although Yemen’s security services have preempted several such operations. Typical of the “revolving door” approach to terrorism prosecutions that irks the United States is the case of two Yemenis convicted of trying to assassinate U.S. Ambassador Edmund James Hull (an important official in U.S. counter-terrorism efforts) in 2004. Only days after Saleh’s return from Washington, the two convicts had their sentences reduced from five years to three on appeal (AFP, May 7).

Shaykh Muhammad Ali Hassan al-Moayyad

Shaykh Muhammad Ali Hassan al-Moayyad

Yemeni Prisoners in the United States

During his visit to Washington, President Saleh asked for the repatriation of Shaykh Muhammad Ali Hassan al-Moayyad, a Yemeni religious scholar extradited from Germany to the United States (along with his assistant Muhammad Za’id), where he is serving a prison term after being convicted of supporting Hamas (but acquitted of supporting al-Qaeda). Yemeni human rights organizations are agitating for the shaykh’s release on the grounds of declining health. The head of a national committee to free al-Moayyad (who is popular in Yemen for his charitable work) notes that, since “Europe and the whole international community are (now) dealing with Hamas as an independent entity, why is it forbidden for al-Moayyad?” (Yemen Observer, April 25).

Saleh also discussed the case of Yemeni citizens held in Guantanamo Bay. Although official Yemeni sources claim that Saleh requested the release of all the Yemeni Guantanamo Bay prisoners, there are signs that Yemen’s government is not overeager for their repatriation. In a March visit to Yemen, Marc Falkoff, a lawyer for 17 of the Yemeni detainees, revealed that he had obtained documents from the Pentagon showing that many of the Yemeni prisoners had been eligible for repatriation as far back as June 2004. The Yemeni government justifies its inaction by claiming that the citizenship of some of the Yemeni detainees is under question. According to Falkoff, “Fully one-third of the Saudis are back in Saudi Arabia, more than half of the Afghanis are home with their families and every single European national has been released from Guantanamo. Yet, more than 100 Yemenis remain at the prison—sitting in solitary confinement on steel beds, deprived of books and newspapers, slowly going insane” (Yemen Times, March 11).

U.S. officials claim that there are 107 Yemeni prisoners at Guantanamo, while human rights activists cite as many as 150, but there is no doubt that Yemenis form the largest single group of foreign nationals detained at the facility. Although the government may be in no hurry for their return, reports of alleged torture practiced on Yemeni detainees in U.S.-run detention centers have inflamed anti-American sentiment in Yemen.

The Case of al-Zindani

Saleh also requested that the U.S. drop Yemen’s controversial Shaykh Abd al-Majid al-Zindani from its list of designated terrorists. Believed by U.S. intelligence services to be an important link to bin Laden and al-Qaeda, the sheikh’s terrorist designation has been an unrelenting irritant to U.S.-Yemeni relations. The sheikh is a powerful member of the Islamist Islah Party and has close ties to Saleh’s administration. Yemen’s parliament recently rescinded a decision to join the International Criminal Court (ICC) system, largely because of the fear of Islah Party MPs that the ICC could be used as a tool to extradite and try al-Zindani on terrorism charges (al-Thawri, May 2). Apparently, Shaykh al-Zindani has lately joined the call for religious scholars to correct the mistakes in Islamic interpretation that promote dissension and political violence (Yemen Observer, May 2).

Conclusion

Security issues and concerns with government reforms led donor states to suspend economic aid to Yemen two years ago, but President Saleh’s reform efforts appear to have regained the confidence of the international donor community. Despite the detention of political activists and opposition candidates during the 2006 election campaign, Saleh’s new seven-year term as president is regarded as a sign of stability. European aid is flowing once again, and in February the Bush administration announced that Yemen was once more eligible to receive funds from the Millennium Challenge Account (MCA) (tied to progress in governance). Of the $94 million released by the MCA, $59 million is dedicated to the military and security sector (Saba News Agency, May 3). The aid represents vital assistance to Yemen’s weak economy. Unemployment persists at about 40 percent, there is little development and Yemen’s small petroleum industry does not enjoy the bountiful reserves found in its prosperous Arabian Peninsula neighbors.

While Saleh cannot ignore the general discontent within Yemen regarding U.S. foreign policy, he also recognizes that cooperation with the United States is the best method of ensuring the survival of his regime. Methods such as the “dialogue with extremists” and the “revolving door” of the judicial system allow Saleh to keep a lid on Sunni radicalism, while at the same time posing as a vital ally of the United States. Despite the apparent success of Saleh’s visit to Washington, there is still much to concern the United States in its relationship with Yemen. Reforms to the security services have notably involved purges of al-Qaeda sympathizers at only the lowest levels. Yemeni extremists continue to join anti-coalition forces in Iraq and have been involved in terrorist operations in several countries as President Saleh continues his search for a “third option” in the war on terrorism.

This article was first published in the May 10, 2007 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor