Andrew McGregor

April 3, 2009

Over the last few months, the strategically important African Red Sea coast has suddenly become the focal point of rumors involving troop-carrying submarines, ballistic missile installations, desert-dwelling arms smugglers, mysterious airstrikes and unlikely alliances. None of the parties alleged to be involved (including Iran, Israel, Eritrea, Egypt, Sudan, France, Djibouti, Gaza and the United States) have been forthcoming with many details, leaving observers to ponder a tangled web of reality and fantasy. What does appear certain, however, is that the regional power struggle between Israel and Iran has the potential to spread to Africa, unleashing a new wave of political violence in an area already consumed with its own deadly conflicts.

Israeli Air Force F-16I Sufa (Storm)

Israeli Air Force F-16I Sufa (Storm)

Airstrike in the Desert

Though an airstrike on a column of 23 vehicles was carried out on January 27 near Mt. Alcanon, in the desert northwest of Port Sudan, news of the attack first emerged in a little-noticed interview carried on March 23 in the Arabic-language Al-Mustaqillah newspaper (see https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=1854). In the interview, Sudanese Transportation Minister Dr. Mabruk Mubarak Salim, the former leader of the Free Lions resistance movement in eastern Sudan, said that aircraft he believed to be French and American had attacked a column of vehicles in Sudan eastern desert after receiving intelligence indicating a group of arms smugglers was transporting arms to Gaza. Dr. Salim’s Free Lions Movement was based on the Rasha’ida Arabs of east Sudan, a nomadic group believed to control smuggling activities along the eastern Egypt-Sudan border.

On March 26, Dr. Salim told al-Jazeera there had been at least two airstrikes, carried out by U.S. warplanes launched from American warships operating in the Red Sea. There was no further mention of the French, who maintain an airbase in nearby Djibouti. After the news broke in the media, Sudanese foreign ministry spokesman Ali al-Sadig issued some clarifications:

The first thought was that it was the Americans that did it. We contacted the Americans and they categorically denied they were involved… We are still trying to verify it. Most probably it involved Israel… We didn’t know about the first attack until after the second one. They were in an area close to the border with Egypt, a remote area, desert, with no towns, no people (Al-Jazeera, March 27).

With the Americans out of the way, suspicion fell on Israel as the source of the attack.

Sudanese authorities later claimed the convoy was carrying not arms, but a large number of migrants from a number of African countries, particularly Eritrea (Al-Sharq al-Awsat, March 27; Sudan Tribune, March 28). According to Foreign Minister Ali al-Sadig; “it is clear that [the attackers] were acting on bad information that the vehicles were carrying arms” (Haaretz, March 27). Dr. Salim claimed the death toll was 800 people, contradicting his earlier claim that the convoy consisted of small trucks carrying arms and that most of those killed were Sudanese, Ethiopians and Eritreans (al-Jazeera, March 26). There was also some confusion about the number of attacks, with initial claims of a further strike on February 11 and a third undated strike on an Iranian freighter in the Red Sea. The latter rumor may have had its source in Dr. Salim’s suggestion that several Rasha’ida fishing boats had been attacked by U.S. and French warplanes. Otherwise, no evidence has been provided to substantiate these claims.

A Hamas leader, Salah al-Bardawil, denied his movement had any knowledge of such arms shipments, pointing to the lack of a common border between Gaza and Sudan as proof “these are false claims” (Al-Jazeera, March 27).

A Smuggling Route to Sinai?

The alleged smuggling route, beginning at Port Sudan, would take the smugglers through 150 miles of rough and notoriously waterless terrain to the Egyptian border and the disputed territory of Hala’ib, currently under Egyptian occupation. From there the route would pass roughly 600 miles through Egypt’s Eastern Desert, a rocky and frequently mountainous wasteland. Criss-crossing the terrain to find a suitable way through could add considerably to the total distance. North of the Egyptian border the Sudanese smugglers would be crossing hundreds of miles of unfamiliar and roadless territory. The alternatives would involve offloading the arms near the border to an Egyptian convoy or making a change of drivers. Anonymous “defense sources” cited by the Times claimed local Egyptian smugglers were engaged to take over the convoy at the Egyptian border “for a fat fee” (The Times, March 29).

Use of the well-patrolled coastal road would obviously be impossible without official Egyptian approval. The other option for the smugglers would be to cut west to the Nile road which passes through hundreds of settled areas and a large number of security checkpoints. The convoy would need to continually avoid security patrols along the border and numerous restricted military zones along the coast. Either Egyptian guides or covert assistance from Egyptian security services would be needed for a 23 vehicle convoy to reach Sinai from the Egyptian border without interference. Once in the Sinai there is little alternative to taking the coastal route to Gaza, passing through one of Egypt’s most militarily sensitive areas, to reach the smuggling tunnels near the border with Gaza.

Water, gasoline, spare parts and other supplies would take up considerable space in the trucks. Provisions would have to be made for securing and transporting the loads of disabled trucks that proved irreparable, particularly if their loads included parts for the Fajr-3 rockets the convoy was alleged to be carrying, without which the other loads might prove unusable. Freeing the trucks from sand (a problem worsened by carrying a heavy load of arms) and making repairs could add days to the trip. The alleged inclusion of Iranian members of the Revolutionary Guard in the convoy would be highly risky – if stopped by Egyptian security forces, every member of the arms convoy would be detained and interrogated (Israeli sources claimed several Iranians were killed in the raid). It would not take long to separate the Iranians from the Arabs, with all the consequences that would follow from the exposure of an Iranian intelligence operation on Egyptian soil.

Of course most of these problems would disappear if Egypt was giving its approval to the arms shipments. But if this was the case, why not send the arms through Syria and by ship to a port near the Gaza border? Ships are the normal vehicle for arms deliveries as massive quantities of arms are usually required to change the military balance in any situation.

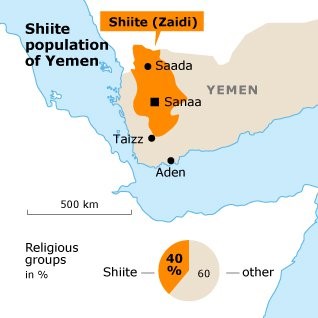

Israel’s Haaretz newspaper reported that the arms were “apparently transferred from Iran through the Persian Gulf to Yemen, from there to Sudan and then to Egypt through Sinai and the tunnels under the Egypt Gaza border” and included “various types of missiles, rockets, guns and high-quality explosives” (Haaretz, March 29). The Yemen stage is unexplained; Iranian ships can easily reach Port Sudan without a needless overland transfer of their cargos in Yemen before being reloaded onto ships going to Port Sudan. Looking at this route (the simplest of several proposed by Israeli sources), one can only assume Hamas was in no rush to obtain its weapons.

Reserves Major General Giyora Eiland, a former head of Israel’s National Security Council, alleged the involvement of a number of parties in the Sinai to Gaza arms trade, including “Bedouin and Egyptian army officers who are benefiting from the smuggling.” He then turned to the possibility of arms being shipped through Sudan to Gaza; “Almost all of the weapons are smuggled into Gaza through the Sinai, and some probably by sea. Little comes along this long [Sudan to Gaza] route” (Voice of Israel Network, March 27).

Video footage of the burned-out convoy was supplied to al-Jazeera by Sudanese intelligence sources. The footage shows only small pick-up trucks, largely unsuitable for transporting heavy arms payloads. If Fajr-3 missiles broken down into parts were included in the shipment, there would be little room for other arms (each Fajr-3 missile weighs at least 550 kilograms). Sudanese authorities described finding a quantity of ammunition, several C-4 and AK-47 rifles and a number of mobile phones used for communications by the smugglers. There was no mention of missile parts (El-Shorouk [Cairo], March 24). No evidence has been produced by any party to confirm the origin of the arms allegedly carried by the smugglers’ convoy.

Assessing Responsibility

Citing anonymous “defense sources,” the Times claimed the convoys had been tracked by Mossad, enabling an aerial force of satellite-controlled UAVs to kill “at least 50 smugglers and their Iranian escorts” (The Times [London], March 29). American officials also reported that at least one operative from Iran’s Revolutionary Guards had gone to Sudan to organize the weapons convoy (Haaretz/Reuters, March 27). According to the Times’ sources, the convoy attacks were carried out by Hermes 450 and Eitan model UAVs in what would have been an aviation first – a long distance attack against a moving target carried out solely by a squadron of remote control drones.

U.S.-based Time Magazine entered the fray on March 30 with a report based on information provided by “two highly-placed Israeli security sources.” According to these sources, the United States was informed of the operation in advance but was otherwise uninvolved. Dozens of aircraft were involved in the 1,750 mile mission, refuelling in midair over the Red Sea. Once the target was reached, F15I fighters provided air cover against other aircraft while F16I fighters carried out two runs on the convoy. Drones with high-resolution cameras were used to assess damage to the vehicles.

The American-made F16I “Sufa” aircraft were first obtained by the IAF in 2004. They carry Israeli-made conformal fuel tanks to increase the range of the aircraft and use synthetic aperture radar that enables the aircraft to track ground targets day or night. The older F15I “Ra’am” is an older but versatile model, modified to Israeli specifications.

The entire operation, according to the Israeli sources used by Time, was planned in less than a week to act on Mossad information that Iran was planning to deliver 120 tons of arms and explosives to Gaza, “including anti-tank rockets and Fajr rockets with a 25 mile range” in a 23 truck convoy (though this shipment seems impossibly large for 23 pick-up trucks with a maximum payload capacity of one ton or less – on paved roads). The Israeli sources added that this was the first time the smuggling route through Sudan had been used.

Israeli officials claimed anonymously that the convoy was carrying Fajr-3 rockets capable of reaching Tel Aviv (Sunday Times, March 29; Jerusalem Post, March 29). The Fajr-3 MLRS is basically an updated Katyusha rocket that loses accuracy as it approaches the limit of its 45km range and carries only a small warhead of conventional explosives. It has been suggested that the missiles carried by the convoy “could have changed the game in the conflict between Israel and Palestinian militants,” thus making the attack an imperative for Israel (BBC, March 26). Yet far from being “a game-changer,” the Fajr-3 was already used against Israel by Hezbollah in 2006. It has also been claimed that the Fajr-3 rockets could be used against Israel’s nuclear installation at Dimona, but Israeli officials reported at the start of the year that Hamas already possessed dozens of Fajr-3 rockets (Sunday Times, January 2). Some media accounts have confused the Fajr-3 Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS), which would seem to be the weapon in question, with the much larger Fajr-3 medium-range ballistic missile.

Reports of the complete destruction of the entire convoy and all its personnel raise further questions. Desert convoys tend to be long, strung out affairs, not least because it is nearly impossible to drive in the dust of the vehicle ahead. Could an airstrike really kill every single person involved in a strung out convoy without a ground force going in to mop up? UAVs with heat sensors and night vision equipment might have remained in the area to eliminate all survivors, but this seems unnecessary if the arms had already been destroyed. The political risk of leaving Israeli aircraft in the area after the conclusion of a successful attack would not equal the benefit of killing a few drivers and mechanics.

What role did Khartoum play in these events? A pan-Arab daily reported that the United States warned the Sudanese government before the Israeli airstrike that a “third party” was monitoring the arms-smuggling route to Gaza and that such shipments needed to stop immediately (Al-Sharq al-Awsat, March 30). Despite state-level disagreements, U.S. and Sudanese intelligence agencies continue to enjoy a close relationship.

With Sudan under international pressure as a result of the Darfur conflict, Khartoum has sought to renew its relations with Iran. Less than two weeks before the airstrike, Sudanese Defense Minister Abdalrahim Hussein concluded a visit to Tehran to discuss arms sales and training for Sudanese security forces. An Iranian source reported missiles, UAVs, RPGs and other equipment were sought by Sudan (Sudan Tribune, January 20).

An Iranian Base on the Red Sea?

As tensions rise in the region, wild allegations have emerged surrounding the creation of a major Iranian military and naval base in the Eritrean town of Assab on the Red Sea coast. Assab is a small port city of 100,000 people. A small Soviet-built oil refinery at Assab was shut down in 1997. Last November an Eritrean opposition group, the Eritrean Democratic Party, published a report on their website claiming Iran had agreed to revamp the small refinery, adding (without any substantiation) that Iran and Eritrea’s President Isayas Afewerki were planning to control the strategic Bab al-Mandab Straits at the southern entrance to the Red Sea (selfi-democracy.com, November 25, 2008).

Main Street in Assab: New Iranian Military Base?

Main Street in Assab: New Iranian Military Base?

A short time later, another Eritrean opposition website elaborated on the original report of a refinery renovation, adding lurid details of Iranian ships and submarines deploying troops and long-range ballistic missiles at a new Iranian military base at Assab. Security was allegedly provided by Iranian UAVs that patrolled the area (EritreaDaily.net, December 10, 2008).

The Israeli MEMRI website then reported that “Eritrea has granted Iran total control of the Red Sea port of Assab,” adding that Iranian submarines had “deployed troops, weapons and long-range missiles… under the pretext of defending the local oil refinery” (MEMRI, December 1, 2008).

The story was further elaborated on by Ethiopian sources (Ethiopia and Eritrea are intense rivals and political enemies). According to one Ethiopian report, Iranian frigates were using Assab as a naval base (Gedab News, January 28). An Ethiopian-based journalist contributed an article to Sudan Tribune in which he again claimed Iranian submarines were delivering troops and long-range missiles to Assab, basing his account on the original report on selfi-democracy.com, which made no such claims (Sudan Tribune, March 30). Israel’s Haaretz noted that Addis Ababa is “a key Mossad base for operations against extremist Islamic groups” in the region, adding that some of the weapons destroyed in the convoy had “reportedly passed through Ethiopia and Eritrea first” (Haaretz, March 27).

Only days ago, a mainstream Tel Aviv newspaper reported that Iran has already finished building a naval base at Assab and had “transferred to this base – by means of ships and submarines – troops, military equipment and long range-ballistic missiles… that can strike Israel.” The newspaper claimed its information was based on reports from Eritrean opposition members, diplomats and aid organizations, without giving any specifics (Ma’ariv [Tel Aviv], March 29). On March 19, Israel’s ambassador to Ethiopia accused Eritrea of trying to sabotage the peace process in the region by serving as a safe haven for terrorist groups (Walta Information Center [Addis Abbab], March 19). In only four months, a minor refinery renovation was transformed into a strategic threat to the entire Middle East.

Conclusion

Questions remain as to how the moving convoy was found by its attackers. Did Mossad have inside intelligence? Did the Israelis use satellite imagery from U.S. surveillance satellites as part of the agreement they signed in January on the prevention of arms smuggling to Gaza, or did they use their own Ofeq-series surveillance satellites? Was an Israeli UAV already in place when the convoy left Port Sudan? A retired Israeli Air Force general, Yitzhak Ben-Israel, recognized the difficulty involved in finding and striking the convoy by noting; “The main innovation in the attack on Sudan… was the ability to hit a moving target at such a distance. The fact that Israel has the technical ability to do such a thing proves even more what we are capable of in Iran” (Haaretz, March 27).

The two-month silence on the attacks from other parties is also notable – it is unlikely U.S. and French radar facilities in Djibouti would have missed squadrons of Israeli jets and UAVs attacking a target in nearby East Sudan. If the Israelis took the shortest route through the Gulf of Aqaba and down the Red Sea they would likely be detected by Egyptian and Saudi radar on their way out and on their way back. According to former IAF commander Eitan Ben-Eliyahu, the attack would require precise intelligence and a two and a half hour flight along the Red Sea coast, keeping low to evade Egyptian and Saudi radar. The aircraft would also require aerial refuelling (Haaretz, March 27).

Even if the aircraft evaded radar, their low flight paths would have exposed them to visual observation in the narrow shipping lanes of the Red Sea. Israeli aircraft would almost certainly have been tracked by the Combined Task Force-150, an allied fleet patrolling the Red Sea. All other routes would have taken the aircraft through unfriendly airspace. By March 27, an Egyptian official admitted that Egypt had indeed known of the airstrike at the time, but added the Israelis had not crossed into Egyptian airspace (Al-Sharq al-Awsat, March 27).

If Tehran was involved in this remarkably complicated smuggling operation, it will now be taking its entire local intelligence infrastructure apart to find the source of the leak. Egypt is reported to have deployed additional security personnel along the border with Sudan, effectively closing the alleged smuggling route (Haaretz, March 29). As Sudan revives its defense relationship with Iran it is very likely rumors and allegations will continue to proliferate regarding an Iranian presence on the Red Sea.

This article first appeared in the April 3, 2009 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor