Andrew McGregor

May 29, 2013

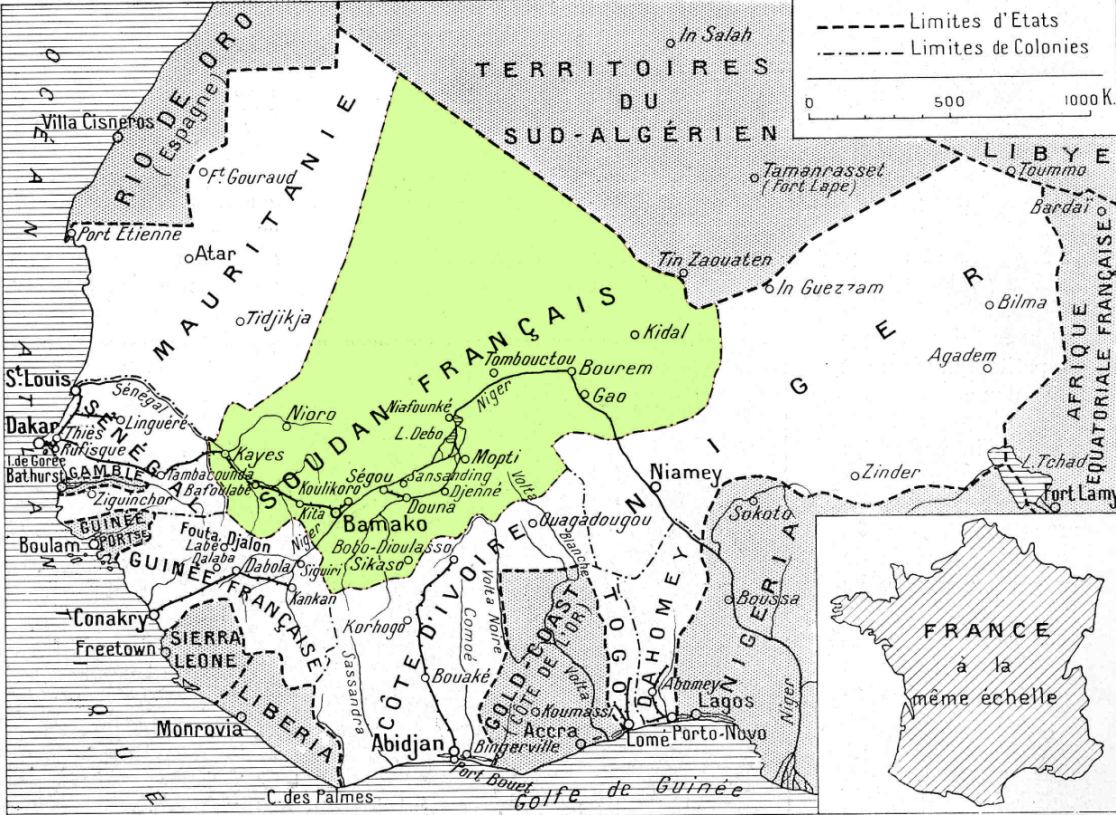

When a pair of suicide bombings occurred almost simultaneously at important economic and military targets in Niger last week, it raised the specter of broadening Salafi-Jihadist activities paralyzing the political and economic development of a vast stretch of north and west Africa. Niger, possibly the poorest nation in the world, has seen the resource industries that are its hope for the future become the focus of radical Islamist efforts to damage French interests in the region.

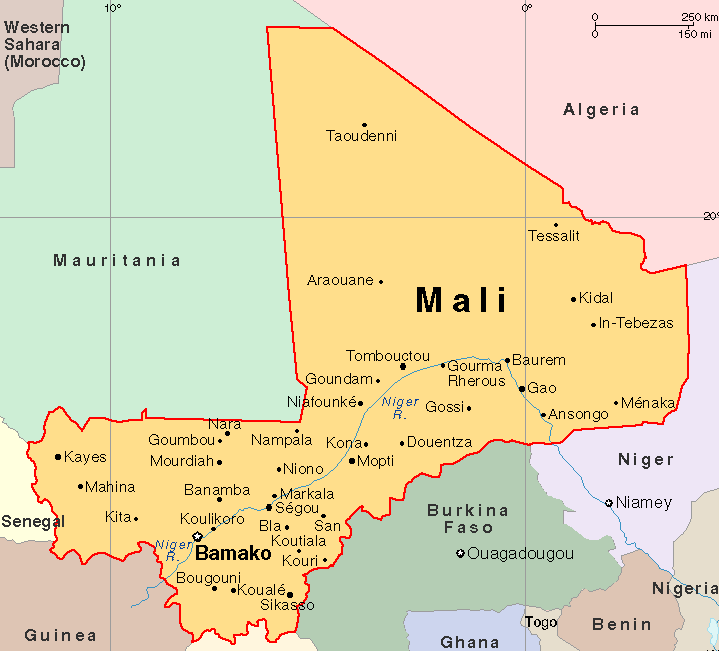

Despite being over 90% Muslim, Niger’s citizens find themselves threatened by the growing presence of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its associates in its northern regions and troublesome incursions by Nigerian Boko Haram militants and bandits posing as Boko Haram in its eastern regions. With a small and poorly equipped military of only 5,200 troops, the intensification of militant activity in Niger may force Niamey to recall its force of roughly 600 soldiers from the Malian intervention and may possibly preclude Niger’s participation in the UN peacekeeping force planned for deployment in northern Mali.

Despite being over 90% Muslim, Niger’s citizens find themselves threatened by the growing presence of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its associates in its northern regions and troublesome incursions by Nigerian Boko Haram militants and bandits posing as Boko Haram in its eastern regions. With a small and poorly equipped military of only 5,200 troops, the intensification of militant activity in Niger may force Niamey to recall its force of roughly 600 soldiers from the Malian intervention and may possibly preclude Niger’s participation in the UN peacekeeping force planned for deployment in northern Mali.

The Attacks at Agadez and Arlit

A dawn double car-bombing against a military base in Agadez on May 23 killed at least 18 soldiers and left 13 wounded (RFI, May 23). After four of the attackers (all wearing suicide belts) were killed by Nigérien troops, one or two others took two officer cadets hostage and locked themselves in an office (AFP, May 23). At the request of President Issoufou, French Special Forces assisted Nigérien troops in isolating and killing the last attackers on May 24 (RFI, May 26). In all, some ten jihadists were reported killed in the action. Nigérien authorities initially denied that any hostages were taken by the surviving attackers, but later admitted both cadets were killed, though it remained unclear if they were killed by the Islamists or in the crossfire during the assault by Nigérien troops and French Special Forces (AFP, May 24; Reuters, May 24). The massive explosions at the military base created panic in Agadez, followed by military sweeps of the city looking for the suicide bombers’ accomplices.

A second attack roughly 30 minutes later targeted the Somaïr uranium mining and processing plant located seven kilometers from the northern Niger town of Arlit. A uniformed suicide bomber pulled his explosives-laden 4X4 in behind a bus delivering workers to the morning shift at the plant and forced his vehicle through the plant’s entrance before the gates could be closed. The tactic was identical to that used by a MUJWA suicide car-bomber at the National Gendarmérie headquarters in the southern Algerian town of Tamanrasset (the home of the Algerian Army’s 6th Division) in early March, 2012 (La Tribune [Algiers] March 3; Le Temps D’Algérie, March 6).At least 13 employees were injured and one killed in the Arlit attack, which took place just outside the facility’s power plant and badly damaged the mine’s grinding and crushing machinery (RFI, May 23). Somaïr is a Nigérien subsidiary of French uranium giant Areva, which owns 64% of the Arlit uranium mine.

Information gathered at the French Ministry of Defense in Paris indicated that the Arlit attackers had taken advantage of the fact that French Special Forces were not actually located at the camp, but were rather based nearby, thus creating what a French colonel described as “an enormous flaw in the security process” (RFI, May 24). Arlit had been targeted before: in September, 2010, seven Areva employees and a local sub-contractor were kidnapped from the site. Four French hostages from that operation remain in the hands of AQIM, though their current whereabouts is unknown.

Though Niger has been the target of AQIM kidnapping operations in the past, suicide bombings are a tactical innovation for Islamists operating in that nation. Nigérien troops in northern Mali were targeted by a May 10 MUJWA suicide attack on their base in Ménaka, close to the Niger border (see Terrorism Monitor Brief, May 16).

Who is Behind the Assault on Niger?

It appears the bombings in Niger were directed by Mokhtar Belmokhtar (a.k.a. Khalid Abu al-Abbas), the Algerian jihadist who became North Africa’s most-wanted man after a January attack on the Algerian gas plant at In Aménas left 38 hostages dead. That attack was carried out by Belmokhtar’s al-Muwaqi’un bi’l-Dima (Those Who Sign in Blood) Brigade, which Belmokhtar announced was also responsible for the attacks in Arlit and Agadez. Belmokhtar’s claim of responsibility contained a number of pointed warnings to the Niger government related to Niger’s participation in Operation Serval, the French-led military intervention in northern Mali. After stating that the suicide attacks in Niger were intended to avenge his late comrade and rival, AQIM commander Abd al-Hamid Abu Zeid (a.k.a. Muhammad Ghadir), Belmokhtar said the attacks were also a “first response” to the claim by the Nigérien president that the jihad in northern Mali had been defeated militarily. Describing this “crusade against Shari’a” as “more a media victory than a military victory,” Belmokhtar then warns the Nigérien president that the mujhahideen will “move the war into his own country if he doesn’t withdraw his mercenary army [from Mali]” (Ansar1.info, May 23).

Adnan Abdul al-Walid al-Sahrawi

Adnan Abdul al-Walid al-Sahrawi

Responsibility for the attacks was initially claimed by spokesman Adnan Abdul al-Walid al-Sahrawi on behalf of the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJWA). According to al-Sahrawi, the operations were conducted “against the enemies of Islam in Niger. We attacked France and Niger for its cooperation with France in the war against Shari’a” (AFP, May 23). Some clarification was later received from the AQIM Mulathamin Brigade’s Mauritanian spokesman Hassan Ould al-Khalil, who described the operation as a joint effort between MUJWA and Belmokhtar’s al-Muwaqi’un bi’l-Dima, adding that the attackers hailed from Sudan, Mali and the Western Sahara (al-Akhbar [Nouakchott], May 23).Niger’s foreign affairs minister, Muhammad Bazoum, downplayed the importance of determining which Islamist faction actually carried out the attacks: “In my opinion, we are faced with a well-coordinated ‘international’ group which gets its supplies from the same sources of finance, which has the same expertise and the same logistics. Whether it is MUJWA or another group, there is no difference from our point of view” (RFI, May 24).

It is possible that the attacks may have involved Nigérien MUJWA fighters who have returned to Niger since the beginning of Operation Serval. According to Foreign Affairs Minister Muhammad Bazoum, many Peul/Fulani youth were recruited by MUJWA from Tillabéri, a town on the Niger River, about 120 kilometers northwest of the capital of Niamey (RFI, May 24). According to Niger’s minister of the interior, many of the Peul/Fulani recruits to MUJWA had been involved in a long struggle with Niger’s Tuareg and the conflict in northern Mali offered an opportunity to take armed revenge on the Tuareg while making good money in the employ of the Islamists (Jeune Afrique, April 29). Tillabéri now hosts some 30,000 refugees from the northern Mali conflict in three camps and is currently in the midst of a cholera epidemic (Xinhua, May 21). There are also fears that militants could easily disguise themselves as refugees under current conditions in order to enter Niger or other countries neighboring northern Mali. Mali is not the only source for refugees in Niger; several thousand Niger citizens, many of the Koranic students from Maiduguri, have been forced to flee back into Niger from the fighting between Boko Haram and the Nigerian security services during the ongoing Nigerian government offensive (RFI, May 18; May 22).

Only two days before the attacks on Arlit and Agadez, Niamey had hosted the Nigerian minister of state for foreign affairs, Nurudeen Muhammad, who was there to request military assistance from Niger in the fight against Boko Haram terrorists in the Lake Chad region amidst rumors (denied by Abuja) that Nigeria would draw down its commitment to AFISMA in northern Mali to assist in the offensive against Boko Haram (RFI, May 22; Reuters, May 21). Nigeria and Niger share a poorly regulated 940 mile border. The two nations agreed on a defense pact last October that calls for intelligence sharing, joint military exercises and military support when requested (Reuters, May 21). Boko Haram militants attacked a joint patrol of Nigerian and Nigérien troops on April 15 along the border near Baga in the Lake Chad region (AFP, April 26).

Economic Factors

In condemning the attacks in Niger, Malian foreign minister Tièman Coulibaly noted that “In the fight against terrorists in the Sahel, we don’t only need a military and security solution, but also economic solutions that offer young men in the sub-region opportunities (PANA Online [Dakar], May 24). However, despite the presence of enormous quantities of uranium ore and the recent emergence of a promising oil industry, life in Niger remains both harsh and precarious, offering the potential for embittered local residents to join attacks on foreign dominated industries that do not appear to benefit the impoverished general population.

Nigérien uranium fuels France’s domestic nuclear energy program and its nuclear weapons program. With most of its uranium extraction industry in the hands of French mining giant Areva, Niger now ranks as the world’s fourth largest producer of the mineral. Niamey would like to renegotiate what it regards as an unfavorable deal with Areva and to see uranium operations expanded, but a combination of political unrest in the ore-bearing region and depressed global uranium prices have led Areva to several times put off development of the giant mine at Imouraren, which is now scheduled to open in 2015 (AFP, May 23). In these conditions, the industry actually has only a small impact on Niger’s desperately impoverished economy. Niamey is trying to address the problem by diversifying the industry, granting uranium exploration licenses to Canadian, Indian and Australian firms.

The initiation of Chinese oil operations in the eastern province of Diffa (near Lake Chad) have only brought unrest to the region due to the perception that oil revenues fail to benefit the Diffa region and hiring practices that effectively exclude locals. Unemployed youth who used to be able to find employment in Libya rioted for in Diffa for three days recently, demanding priority in hiring at the Chinese drilling site (RFI, April 29; April 29; May 3).

The Tuareg Question

The majority of Niger’s population belongs to the Hausa and Djerma-Songhai ethnic groups. As in Mali, the Tuareg (who make up roughly 10% or Niger’s population of 17 million) share the more arid northern regions of Niger with other ethnic groups, including Tubu (who have joined the Tuareg in past rebellions and have connections to the Tubu militias of southern Libya), Arabs, Kanuri and Peul/Fulani. However, fears that the Tuareg rebellion in Mali might cross the border to Niger have not materialized so far, largely in part due to general dissatisfaction with the human and material costs of the most recent rebellion in 2007-2009 and the relative success of integration efforts in the wake of that conflict. Niger mounted a significant security campaign to intercept, disarm and reintegrate Tuareg veterans of the Libyan military who returned to Niger after the collapse of the Qaddafi regime, encouraging the most militant returnees to bypass Niger after clashing with Nigérien troops and head for northern Mali instead, where government control of the north was much less effective (Jeune Afrique, May 20). Niger has a small but growing Salafist population, concentrated at the moment in Niamey and Maradi, the latter being just north of the border with Nigeria and close to the Islamist stronghold of Kano. Though Salafism enjoyed a brief popularity amongst certain Tuareg supporters of Iyad ag Ghali’s Ansar al-Din movement in Mali, it has made few inroads amongst the mainly Sufi Tuareg of Niger.

Conclusion

Nigérien authorities insist that the suicide bombings that have targeted the Nigérien military and economic infrastructure will not deter Niger from its commitment to counter-terrorist operations carried out in league with France and Niger’s regional allies. French President François Hollande has meanwhile indicated France was willing to help Niger “destroy” Islamic militants operating in that country, but tempered the French commitment by saying: “We will not intervene in Niger as we did in Mali, but we have the same willingness to cooperate in the fight against terrorism” (AFP, May 23). Continued attacks on vital French interests in Niger may change this approach at some point.

The sophistication and effectiveness of the attacks (which contrast with the poorly executed MUJWA suicide attacks in Gao) suggest the participation or supervision of veteran jihadists rather than the enthusiastic but unskilled fighters of MUJWA. Islamist militants appear to have adapted to the increased presence of surveillance drones and aircraft in the region, avoiding the risk posed by long-distance raids in strength by fighting in close, mounting attacks in small numbers that can easily be concealed until the last moment, whether in the urban population of Agadez or in a mass of workers reporting for work at Arlit. Resource industries and military installations continue to present prime targets for their political and economic impact, though it is possible that the militants might turn to more random attacks on the civilian population in Niger if it refuses to back away from counter-terrorist efforts in cooperation with Western partners.

There are also indications that the attacks in Niger are only part of a spread of jihadi activities throughout the Sahel/Sahara region as a consequence of the dispersal of the jihadists who had concentrated in northern Mali before the French-led intervention. After the Niger bombings, Hassan Ould al-Khalil, the spokesman of AQIM’s Mulathamin Brigade, warned his home nation of Mauritania that it could expect similar attacks if it contributed troops to the new UN peacekeeping force being organized for deployment in northern Mali (al-Akhbar [Nouakchott], May 23).

Nigérien president Mahamadou Issoufou maintains that: “According to the information we have, the attackers [in the Agadez and Arlit incidents] came from southern Libya… I know the Libyan authorities are trying hard. But Libya continues to be a source of instability” (Reuters, May 25; for southern Libya’s security crisis, see Terrorism Monitor, April 19). During a May 2 visit to Paris, Niger’s foreign minister, Muhammad Bazoum, had warned of the threat posed by Islamists setting up “international terrorism bases” in loosely governed southern Libya: “Southern Libya is not under the control of the state and we have information that suggests that a certain number of jihadists are now in this area… As long as the Libyan state is a state that is unable to control its borders, there is a risk [to its neighbors]” (Reuters, May 2). With violent extremists such as AQIM’s Mokhtar Belmokhtar operating in the region seemingly at will, it is becoming clear that the effort to sweep terrorists and radical Islamists from northern and western Africa cannot be compartmentalized according to the borders of local nation-states, but must rather be part of a comprehensive and coordinated multi-national effort with significant external assistance. However willing they might be, nations such as Niger simply do not have the resources and manpower to unilaterally ensure security in vast and lightly-populated regions that offer operational bases and useful transit routes for extremists building a more widespread jihad against Western interests and “apostate” governments in northern Africa.

This article first appeared as a Jamestown Foundation “Hot Issue,” May 29, 2013.