Andrew McGregor

August 9, 2013

Bahrain’s Interior Ministry has warned the nation’s largely Shiite political opposition against following through with plans for massive Egyptian-style pro-democracy street demonstrations planned for August 14. The opposition is calling for free elections in the Sunni-dominated monarchy and an end to the authoritative rule of Bahrain’s al-Khalifah royal family.

With the Shi’a representing approximately 70 percent of Bahrain’s population, all calls for democracy in Bahrain are interpreted as a revolutionary rejection of the existing order, which has proven extremely lucrative for Bahrain’s Sunni rulers. Although Bahrain was an historic center for Shi’a commerce and education, its conquest by the Sunni al-Khalifah tribe in 1782 brought permanent changes to the political landscape, especially after Bahrain’s new rulers began to offer incentives to other Sunni tribes to resettle there. The once-dominant indigenous Shi’a soon found themselves on the lowest rung of Bahrain’s new social order. [1]

With the Shi’a representing approximately 70 percent of Bahrain’s population, all calls for democracy in Bahrain are interpreted as a revolutionary rejection of the existing order, which has proven extremely lucrative for Bahrain’s Sunni rulers. Although Bahrain was an historic center for Shi’a commerce and education, its conquest by the Sunni al-Khalifah tribe in 1782 brought permanent changes to the political landscape, especially after Bahrain’s new rulers began to offer incentives to other Sunni tribes to resettle there. The once-dominant indigenous Shi’a soon found themselves on the lowest rung of Bahrain’s new social order. [1]

The current regime has the support of Salafists and the Muslim Brotherhood, both of whom are wary of an alleged “U.S.-Iranian plot” against Bahrain. Though the alliance sounds improbable, allegations of this sort help keep the United States on the margins of the political struggle for Bahrain, which plays host to the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet.

Most of Bahrain’s press is strongly conservative, Sunni-dominated and pro-regime, with frequent commentaries decrying the “naïve Western media’s” inability to distinguish “organized terrorism” from “peaceful unrest calling for democracy,” as well as descriptions of the Arab Spring as a “false wave of change bringing only “destruction, havoc and destabilization” (Akhbar al-Khalij [Manama], July 30; al-Ayyam [Manama], July 30). Other accounts from the pro-regime media condemn the opposition’s use of “terrorist tactics” and “sectarian incitement,” as well as the “abuse of social media” to organize opposition protests and incite violence against security personnel (al-Watan [Manama], July 31; al-Ayyam [Manama], July 31; Akhbar al-Khalij [Manama], July 31).

In his Friday sermon of August 2, Manama’s Shaykh Salah al-Juwdar warned that Bahrain was facing a “relentless war” against terrorism and extremism “supported by Iran, the Shiite Da’wah Party of Iraq and Lebanon’s Hezbollah” (Akhbar al-Khalij [Manama], August 3). Other Sunni clerics have used their Friday sermons to warn against “tolerance and leniency to the forces of evil” and to call for full cooperation with the Emirate’s security forces (Akhbar al-Khalij [Manama], July 27).

The Political Opposition

Bahrain’s opposition consists in the main of five sometimes-feuding but generally cooperative and largely Shi’a organizations, including al-Wifaq (the National Islamic Society); Wa’d (the National Democratic Action Society); al-Ikha National Society, the National Democratic Assembly and the National Democratic Unity Gathering. To these may be added the leftist Progressive Democratic Tribune, constructed from the remains of the old Bahrain Communist Party (al-Wasat [Manama], July 25). Public protests and street demonstrations are often organized by the February 14 Youth Coalition, an opposition group that organizes through social networking sites.

The aims of the opposition were set forth in the October 2012 Manama Document, which compared the “non-democratic government” of Bahrain to the former regimes in Tunisia, Egypt and Yemen. While noting that Bahrain is an oil-producing nation, the document says Bahrain still suffers “from an acute poor distribution of wealth and widespread poverty” that is exacerbated by the concentration of land, wealth and power in the hands of a small number of people. [2]

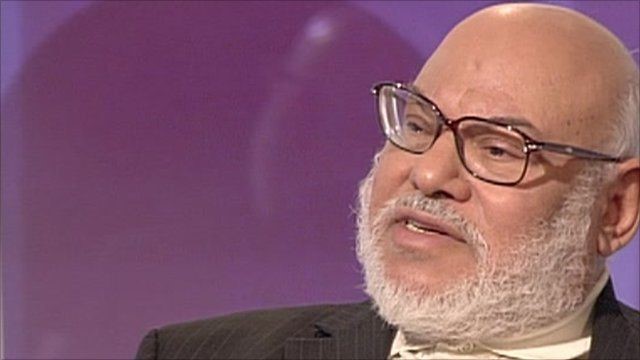

Shaykh Ali Salman

Shaykh Ali Salman

Shiite opposition groups complain that their observance of Ramadan has been marred by continued raids on personal residences and subsequent arrests that have no “legal pretext or judicial order” (al-Wifaq [Manama], July 29). Al-Wifaq general-secretary Shaykh Ali Salman is reported to have received threats from “parties affiliated with the regime” and recently had his home in al-Bidal al-Qadim assaulted by “masked civilian militias” (al-Wifaq [Manama], July 31). Pro-regime media have issued frequent calls for the arrest and detention of Ali Salman, though the Wifaq leader accuses the regime of forcing the “popular movement” to take to the streets due to the former’s reluctance to engage in dialogue, defiantly remarking: “It is an honor to me to be arrested or martyred for the sake of the cause” (al-Wifaq [Manama], July 17; al-Watan [Manama], July 22).

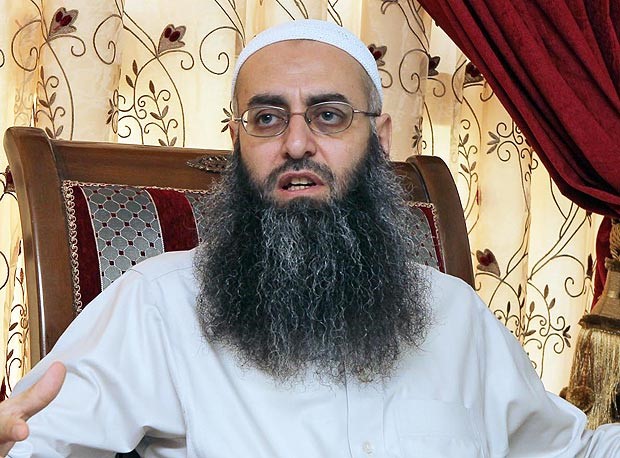

The most important opposition cleric in Bahrain remains Ayatollah Shaykh Isa Ahmad Qassim, whose Friday sermons are often followed by public marches and demonstrations. Isa Qassim, who was accused of organizing an attempted coup in 1996, plays an important but unofficial role in the leadership of al-Wafiq, the most important opposition movement. The regime considers Shaykh Qassim to be an Iranian-backed radical; after Qassim met with a senior U.S. State Department official in May, three Sunni political groups issued a statement saying the meeting exposed the U.S. government’s “support for terrorism operations in Bahrain” (BBC, May 24, 2013). In a recent Friday sermon, al-Qassim said: “the belief that a solution could be struck with the regime is only a mirage… The regime is using its political promises to mask and camouflage its real intentions on the ground – an escalation of violence against its own citizens with utmost ferocity” (Ahlul Bayt News Agency, July 13).

Bahrain’s opposition is of the general belief that the regime has been given a green light by the United States and the Sunni-dominated monarchies of the Gulf to take whatever action is necessary to repress a Shiite-led pro-democracy movement (Fars News Agency [Tehran], July 28). The opposition alleges that their peaceful overtures have been met with repression, collective punishment, killings, torture, abductions, assaults on women and the destruction of Shiite mosques (al-Wasat [Manama], July 31). Much of the political violence takes place in Bahrain’s many Shiite villages, some of which have tried to fortify themselves against incursions by security forces. Such operations tend to finish in clashes with Shiite villagers often using homemade weapons against security personnel.

A Terrorist Threat in Bahrain?

Though charges of “terrorism” are routinely applied by the regime and its supporters to the Shi’a opposition, an actual terrorist campaign has been slow to evolve in Bahrain. An indicator that this might change came in the rather ineffective car-bombing of a mosque parking-lot in the al-Rifa’a suburb of Manama on July 17.

The car-bomb appeared to consist of a single gas cylinder and caused no injuries. One Bahraini daily pointed an improbable finger of responsibility at Lebanon’s Shiite Hezbollah, citing the group’s “specialization” in car-bombs (Akhbar al-Khalij [Manama], July 22). The blast came during evening tarawih prayers (extra night-time congregational prayers conducted during Ramadan) (Akhbar al-Khalij [Manama], July 20). Three suspects were reported to have been arrested on July 27, though neither their identities nor affiliations were given immediately (Ilaf, July 27).

The Rifa’a neighborhood is home to the palaces of the royal family and pro-regime media quickly interpreted the blast as an attempt to strike the royal family. The choice of target may have had some symbolic significance, as the mosque in question was named for Shaykh Isa bin Salman al-Khalifah, Bahrain’s former Amir and the father of the current king. A claim of responsibility was issued by the little-known al-Ashtar Brigade that appeared to support this interpretation: “Our men from al-Ashtar Brigade were able to infiltrate the regime’s headquarters and conduct a unique operation in Rifa’a… We assure that our target is not any place of worship, but it was a final warning to the regime that our men are capable of reaching anywhere and we demand immediate release of our sisters in prison” (Gulf Daily News [Manama], July 19). The reference to “our sisters in prison” appeared to be an attempt to implicate al-Wifaq, which has been campaigning for the release of female detainees. The five main opposition groups responded to al-Ashtar’s statement by issuing a “call for peacefulness and renunciation of violence” (al-Wifaq [Manama], July 26).

In response to the opposition’s rejection of violence, the Ashtar Brigade’s statement included a defense of their methods:

Legitimate resistance is not violence, and the brigade will not abandon resistance and will protect resistance with their blood until Bahrain is liberated from the filth of the al-Khalifah occupiers…With great regret, we have followed the statements of the political opposition societies condemning the legitimate resistance, calling it violence, at a time when the mercenaries of the enemy continue committing the ugliest crimes and violations against the sons of our people… We stress the right of everyone to act in accordance with his viewpoint and his mechanism, be it the approach of resistance or peacefulness (Bahrain Online, July 26).

Despite al-Wifaq’s strong condemnation of the attack and any other form of political violence, Bahrain’s pro-regime press still took the opportunity to speculate on al-Wifaq’s involvement, saying the group “always raises suspicions” or “blesses terrorism” (al-Wifaq [Manama], July 18; al-Watan [Manama], July 18; July 26).

In the days after the parking lot bombing, Bahrain’s pro-regime press carried dozens of formulaic condemnations of the attack from various Sunni Islamic organizations, most of which concluded with a rejection of sectarianism and demands for the immediate and firm application of anti-terrorism legislation. One such statement identified Shaykh Ali Salman and Shaykh Isa Ahmad Qassim as the agents behind the bombing, alleging they were backed by Iran and “Hezbollah terrorists” (Akhbar al-Khalij [Manama], July 20). Ali Salman condemned the bombing, but called for an investigation by a “neutral body,” saying he “does not have to believe the official story” (al-Wifaq [Manama], August 4). Some quarters of the opposition have described the blast as a “fabricated” attack designed to defame and delegitimize the political opposition just as new and repressive legislation is introduced prior to the mid-August protests (Bahrain Mirror, July 19). The bombing was immediately followed by the Interior Ministry’s prohibition of mass-protests scheduled for July 19, followed by a ban on an already rescheduled protest set for July 26 (al-Wasat [Manama], July 21).

Another car bomb exploded near a recreational area west of Manama on August 3, again without casualties. The method appeared similar to the al-Rifa’a bombing, with two gas cylinders used this time, though only one cylinder was successfully detonated.

The Pre-Protest Crackdown

King Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa issued new decrees on August 1 giving authorities wide powers to revoke citizenship for participation in terrorism and to interrupt the funding of groups suspected of supporting terrorist acts (Bahrain News Agency, August 1). Also approved was a bill banning gatherings and rallies in Manama, the Bahraini capital. Friday protests have become common in Manama as opposition supporters call for the release of political prisoners. A number of Sunni MPs have called for Bahraini citizenship to be withdrawn from anyone who “incites terrorism via religious channels or social networking sites” (al-Watan [Manama], July 19). Moderates in the opposition complain they are being forced into the same camp as the more radical opposition due to the regime’s inflexibility.

Bahrain’s security services have repeatedly demanded that local health professionals refuse medical treatment to injured protesters or sought their cooperation in identifying such patients, arresting those doctors and nurses who have displayed reluctance in these efforts. Now, according to a Twitter report from a Manama doctors’ association, the emergency center of the Salmaniya Medical Complex has been put under the authority of the Ministry of the Interior two weeks before the expected protests, complete with security cameras to record those who might seek treatment for demonstration-related injuries (Bahrain Mirror, August 1).

In the crackdown that followed the February, 2011 protests, some 38 Shiite mosques and hussainiya-s (Shiite congregation halls) were destroyed. The government pledged to rebuild these structures, but so far only four mosques have been restored, while the government now looks to use the remaining land for other purposes (as-Safir [Beirut], July 23). Attacks on Shiite mosques have intensified lately both in the capital and in other urban centers, leading Shaykh Ali Salman to ask why officials have failed to address the trend: “Where are the directives to protect sacred places and take measures against perpetrators of such attacks?” (Bahrain Mirror, July 19; al-Alam [Tehran], July 25; as-Safir [Beirut], July 23).

The Role of Iran

Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei sees the political turmoil in Bahrain as part of a larger plot pursued by “Western and Zionist spy agencies” to prevent Islamic unity by sparking dissension in the Muslim community. The Ayatollah has tried to defuse the sectarian aspect of the Bahraini protests, preferring to describe it publically as a natural and understandable preference for the equitable treatment of Bahrain’s majority population: “In Bahrain, an oppressed majority, which has been deprived of the right of voting and other basic rights of a nation for long years, has risen to ask for its rights… Should this strife be seen as a Shiite-Sunni clash only because the oppressed majority is Shiite and the secular and tyrannical government pretends to be Sunni?” (Fars News Agency [Tehran], July 29).

(ABNA)

Iran is especially opposed to the presence of the Gulf Cooperation Council’s multi-nation Peninsular Shield Force and the regime’s reliance on foreign recruitment (particularly from South Asia) for its security forces (for the Peninsular Shield Force, see Terrorism Monitor Brief, March 24, 2011). According to Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister for Arab and African Affairs Hossein Amir Abdollahian: “The continued presence of foreign law enforcement forces in Bahrain and (Manama’s) noncompliance with effective national talks will undermine people’s trust” (Fars News Agency, July 20).

King Hamad insists he is always ready for dialogue with the opposition while alluding to “foreign parties around us who have interest in instability [and] are politically encouraging violence, which certainly threatens Bahrain’s stability… Terror will not be allowed to have a foothold in a country that is a leader in development and civilization” (Ilaf, July 27).

Conclusion

The blast at al-Rifa’a did little to advance the cause of the political opposition in Bahrain; to the contrary, it has diverted attention from the policies of the Khalifah regime and helped authorities paint the opposition as terrorists, or potential terrorists at least. If the international community adopts this view (easily done at a time when Shiites in Lebanon, Syria and Iran are being defined as threats to Western interests and allies in the Middle East), the Khalifah regime will have a free hand in disposing of demonstrators who violate the new “anti-terrorism” laws by taking to the streets in mid-August. Though the planned protests are modeled on those of Egypt, there are significant differences in the two situations; in Bahrain the military is solidly on the side of the regime, foreign military forces are on hand to deal with threats that cannot be contained by Bahrain’s security services, the opposition has only minimal international support and is publicly tainted by its alleged association with the Iranian regime.

Washington’s pro-democracy rhetoric continues to clash with its strategic disinterest in promoting democracy at the risk of jeopardizing American interests in the Middle East, a situation that is complicated by the demands of Shiite pro-democracy activists in Bahrain for protection from the “international community” (i.e. the United States and United Nations) against the regime’s “repeated human rights violations” (al-Wifaq [Manama], July 31). There is a perception amongst some Bahraini politicians that the U.S. ambassador and other foreign envoys are “meddling” in Bahrain’s internal affairs (al-Watan [Manama], July 30).

Though the Manama Document claimed that the regime’s “wrong practices of threatening people demanding reforms and democracy cannot succeed,” there is every sign that the al-Khalifah family will try to ride out the protests scheduled for mid-August knowing they have the full support of their more powerful but similarly autocratic neighbors in the Gulf region. They are also well aware that American support for universal democracy will not overcome fears of a democratically elected Shi’a majority government that could come under Iranian influence in a small nation that provides a vital and highly strategic base for the U.S. Fifth Fleet. There is also a danger that the majority Shi’a population of Saudi Arabia’s oil-producing Eastern Province might be inspired to follow the Bahrain example and produce further instability in the Gulf Region. However, the monarchy’s hard line on political reform has essentially polarized the political debate in Bahrain, with secularists and moderates being pushed aside in a confrontation with increasingly sectarian tones. Cancelling political protests indefinitely is not a sustainable approach to containing political unrest in Bahrain, where attempts to squash the opposition’s mid-August demonstrations through draconian legislation and punitive enforcement could ironically lead to the type of political violence most feared by the Emirate’s rulers.

Notes

- Graham Fuller and Rend Rahim Francke, The Arab Shi’a: The Forgotten Muslims, New York, 1999, pp. 119-123.

- Manama Document, Bahrain Justice and Development Movement, October 12, 2011,http://www.bahrainjdm.org/2011/10/13/manama-document-english/

This article was first published in the Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor, August 9, 2013.