Andrew McGregor

February 22, 2013

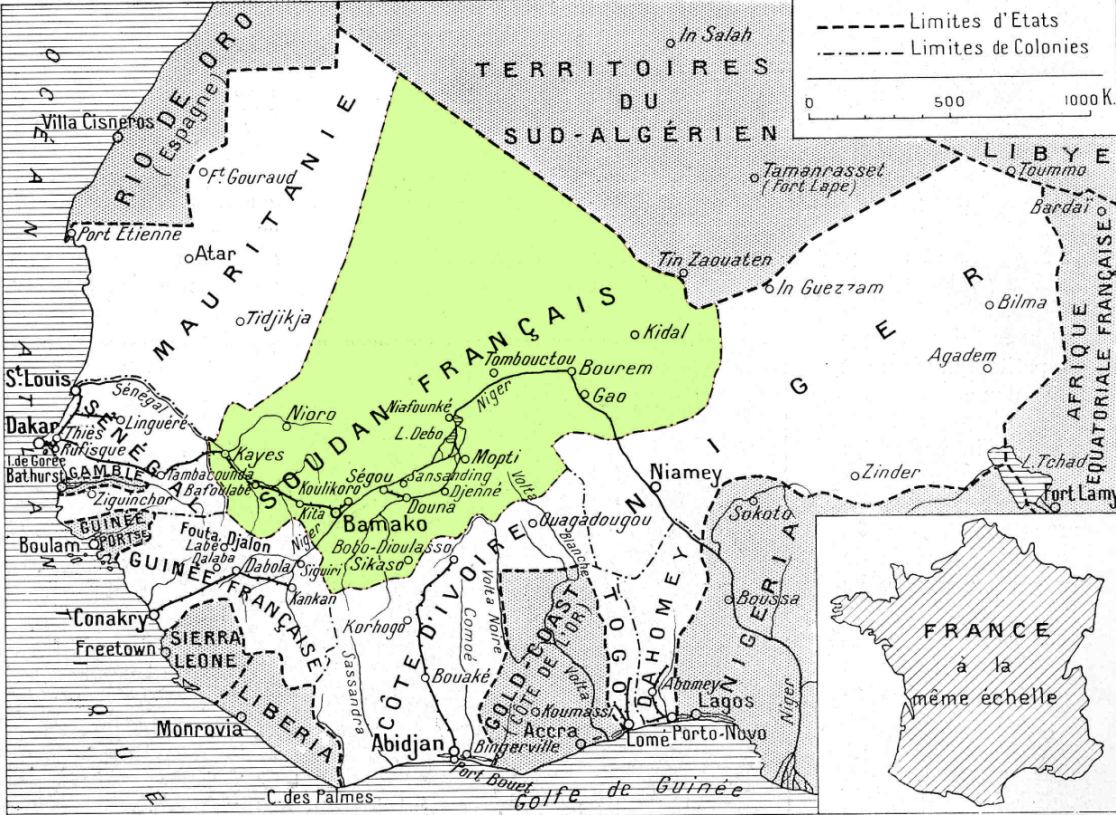

With Paris insisting that the 4,000 French troops involved in the counter-terrorist operations in northern Mali will leave Mali sometime in March, it is worth taking a look at the Malian military that will be called on to secure northern Mali despite the continued presence of armed Islamists in the region. Mali’s interim political administration is still in turmoil, as is the army, which has been at war with itself ever since the March 22, 2012 military coup led by American-trained Captain Amadou Haya Sanogo. The two main factions in the army, broadly described as the pro-junta “Green Berets” and the anti-coup “Red Berets,” have each in their own way hampered the reestablishment of security and national unity in Mali.

Mali’s Red Berets – the 33rd Paratroop Regiment

Mali’s Red Berets – the 33rd Paratroop Regiment

During the March coup, the “Red Berets” of the 33rd Paratroop Regiment, who doubled as the presidential guard, rescued President Ahmadou Toumani Touré and successfully concealed him from the putschists, eventually smuggling him out of the country to safety in Dakar, Senegal. President Touré was himself the former commander of the Red Berets and used the access this gave him to mount his own coup against President Moussa Traoré in 1991. President Touré, who was scheduled to give up his post after the national elections scheduled for May, 2012, resigned in exile on April 8, 2012, allowing the formation of a new interim government in Bamako.

The Counter-Coup

Sanogo’s junta took the name of the Comité National pour le Redressement de la Démocratie et la Restauration de l’État (CNDRE) and appeared to have a firm grip on Mali’s power structures when the Red Berets under their commander Colonel Abidine Guindo mounted a counter-coup attempt in the night of April 30 – May 1, 2012 (Le Republicain [Bamako], May 1, 2012)

Fighting continued through the night, with a focus on the airport, the barracks of various security forces in Bamako, the national TV and radio stations and Sanogo’s headquarters at the Kati military base 15 kilometers outside Bamako. The counter-coup came to an end when pro-junta forces overran the Red Beret base at Djicoroni (outside Bamako) and Colonel Guindo went into hiding. Fourteen soldiers were killed in the fighting and at least 40 wounded.

After the failure of the counter-coup, a number of Red Berets went missing after being detained by security forces, while others were reassigned to other units. Some 400 members of the regiment are now believed to be on active operations with other units in northern Mali, while most of the remaining 800 paratroopers refused to take up their new assignments, insisting that the paratroopers be retained as an operational group.

Captain Amadou Haya Sanogo

Captain Amadou Haya Sanogo

Captain Sanogo blamed the counter-coup on “one single person who made an erroneous assessment of the situation. Colonel Abidine Guindo, head of the parachute regiment, leader of the presidential guard made up of elite troops, thought he could change the political situation and made it a personal problem. He convinced his men I bore them a grudge. It is false” (Jeune Afrique, June 9, 2012).

Arrests and Disappearances

Pro-junta troops swept through Bamako in the days following the failed counter-coup, searching for members of the Red Berets and making 140 arrests, including 40 senior officers (L’Essor [Bamako], May 3; Info Matin [Bamako], May 7, 2012). General Ibrahim Dembélé Dahirou (at the time a Colonel-Major, a French rank between Colonel and Brigadier) met with the 33rd Regiment in late June, 2012 to explain the decision to scatter the unit throughout other formations of the army, but promised to reconstitute the regiment after the liberation of the north was completed (L’Essor [Bamako], June 27).

The families of Red Berets who had been captured or detained before going missing published a list of 21 officers and men who had not been heard from since their detention (L’Indépendant [Bamako], June 29, 2012). According to various human rights organizations, many of the missing appear to have been tortured to death (ANP/AFP, August 10, 2012). As it became clear that many of the arrested Red Berets were disappearing, new attempts to detain members of the regiment began to meet opposition from the women at the Djicoroni camp, who defied teargas and bullets to prevent the entry of security forces seeking to arrest Red Berets (Le Républicain [Bamako], August 4, 2012).

Women Protest for Restoration of Missing Red Berets

Women Protest for Restoration of Missing Red Berets

Nearly a score of paratroopers were reported to have deserted in July, 2012 as officers of the regiment continued to be abducted from their homes (Les Echos [Bamako], July 10, 2012; L’Indépendant [Bamako], July 31, 2012; August 1, 2012). There was a proposal at the time to disband the 33rd and replace it with a new regiment of 1,200 men drawn from the police, the National Guard and the National Gendarmerie (L’Indépendant [Bamako], July 12, 2012).

Colonel Guindo was found and arrested on July 11, 2012 (L’Indépendant [Bamako], July 12, 2012). On October 19, 2012, it was reported that Colonel Guindo had agreed to implicate leading Malian politicians and other figures in the attempted counter-coup, which had come to be known as “the Red Beret affair.” Guindo was also reported to have sought the personal protection of Captain Sanogo (Le Combat [Bamako], October 19, 2012).

The Attack on the Red Beret Base

Tensions within the Malian military peaked when General Dembélé (now army chief-of-general-staff) took to national television to order the recalcitrant paratroopers to the front: “As we have this problem in the north on our hands, you will go and fight with your brothers-in-arms” (AFP, February 8). The fact that these orders were issued via television would seem to indicate the degree to which the command structure in Mali has broken down. Only days before Dembélé issued his new order there had been a glimmer of hope in the paratroopers’ camp that a resolution to their case was near. On January 30, 28 paratroopers and policemen charged with joining in the attempted counter-coup were released from detention. Among those released was former chief-of-staff General Hamidou Sissoko and Squadron Leader Mahamadou Lamine Konaré, the son of deposed president Amadou Toumani Touré (Radio France Internationale, February 2). The release was followed by a rally at the Djicoroni camp calling for the Red Berets to be sent to the front as a unit.

The refusal of the Red Berets to disband and take up new duties in northern Mali was seen as a personal challenge to the authority of General Dembélé, who determined to take action against them. In the early hours of February 8, a security team composed of armed members of the army, air force, police and the National Gendarmerie equipped with a BRDM combat reconnaissance vehicle rolled up to the camp of the 33rd Regiment of Paratroopers at Djicoroni, about halfway between Bamako and the headquarters of the Green Beret putschists at Kati. The security forces attempted to enter the camp, claiming they needed “to secure it,” but were instead faced by a group of angry women and children, the wives and offspring of the Red Beret detainees. Shouting that the security team would need to enter the camp “over our dead bodies,” the women and children initially turned the armed men back with sticks and stones (Le Combat [Bamako], February 14). At this point, the clash turned deadly as the security forces opened fire on the women and children with teargas and live ammunition. Two teenagers were killed and 13 wounded. An exchange of gunfire around the camp continued throughout the morning.

Shortly after the firing stopped, President Dioncounda Traoré called on both factions “to permanently stop these repeated clashes in the Malian army…” (AFP, February 8). The incident was widely regarded as a national embarrassment, with the Malian military apparently pursuing a private feud well behind the lines as soldiers from France, Chad, Niger and elsewhere were fighting to retake northern Mali on behalf of the Bamako government.

The first group of what will ultimately be a force of 500 European Union military trainers arrived on the same day as the confrontation between two factions of the Malian military, providing the trainers with a good indication of the challenges they will face. The leader of the EU mission, French General François Lecointre, noted that the Malian army was “in a state of advanced disrepair… the soldiers are badly trained, badly paid and under-equipped,” and lack arms, transportation and communications equipment (AFP, February 8). The EU training program is scheduled to begin in April and is designed to train four new battalions of 640 men each, with personnel drawn from new recruits and existing units of the Malian military (Reuters, February 20). General Lecointre made it clear that the EU mission was working through contacts with General Dembélé and Mali’s Minister of Defense and Veterans’ Affairs, Brigadier General Yamoussa Camara and had no intention of collaborating in any way with Captain Sanogo.

A wave of arrests, mainly of politicians, followed the confrontation at Djicoroni (JournalduMali.com, February 12). On February 11, General Camara assailed the men still at Djicoroni as “deserters” who should be treated as such while their comrades move up to the front in northern Mali: “This decision has no political connotation. The army has a moral contract vis-à-vis society. All those who stand in the way of this contract will be excluded … There are more than 400 men of the 33rd regiment at the front, and some are even heads of operations” (L’Annonceur [Bamako], February 14; L’Express [Bamako], February 13).

Resolution of the dispute within the Malian military has fallen to Prime Minister Diango Cissoko, who at times appears to be working at odds with his Defense Minister, General Camara, who appears to be seeking the military solution also favored by Captain Sanogo. Cissoko received a delegation of Red Berets led by Colonel Seydou Moussa Diallo on February 12 in hope of reconciling the army’s factions. Cissoko assured the delegation that the regiment had not been dissolved, but notable in his absence from the meeting was the Minister of Defense (Le Pretoire [Bamako], February 14).

Sanogo’s “Honorable Exit”

There is also a question of security for Sanogo and his coup partners, who fear retribution from the friends and families of those who have been killed or disappeared while in the hands of the Green Berets. Getting Sanogo and his comrades out of the Kati military base will depend on a combination of security guarantees, amnesties and personal incentives. Sanogo claims he has no political ambitions while doing everything possible to keep his hands on the reins of power.

As an incentive to step down in favor of a new interim prime minister, Sanogo was granted the status of former head-of-state in April, 2012 with all its perks and benefits, though this status was later withdrawn after a public outcry. The captain was instead confirmed as the head of the newly-created “Committee of Army Reform” on February 15. Though Sanogo gave way to the new government of Cheik Modibbo Diarra, the junta held on to the vital ministries of the interior, defense and territorial administration. After Diarra showed too much independence, Sanogo showed where the real power still lay in Mali by ordering the arrest of the prime minister on December 11, 2012, forcing his resignation a short time later. In May, 2012, Sanogo supporters fought their way past a Red Beret guard detail to assault interim president Dioncounda Traoré, who was stripped naked, beaten and left for dead before he was rescued and sent to France for emergency medical treatment.

Sanogo, who once boisterously claimed he would “fight with his last breath” to retake northern Mali, has instead been sidelined by the conflict as foreign troops mount the campaign without him. Informed that he can join Malian forces operating behind French and Chadian troops as a captain, Sanogo has instead chosen to remain in his newly-constructed and well-guarded house at Kati with other members of the junta who have failed to report for duty in northern Mali (Mali Actualites, February 8). The steady procession of politicians, businessmen and administrators seeking his favor has dried up, however, as the captain finds himself outside of the decision-making process since the arrival of the French. The former putschists are reported to be seeking diplomatic positions abroad or well-financed retirements in Bamako in their discussions with ECOWAS negotiators (Radio France Internationale, February 6).

Conclusion

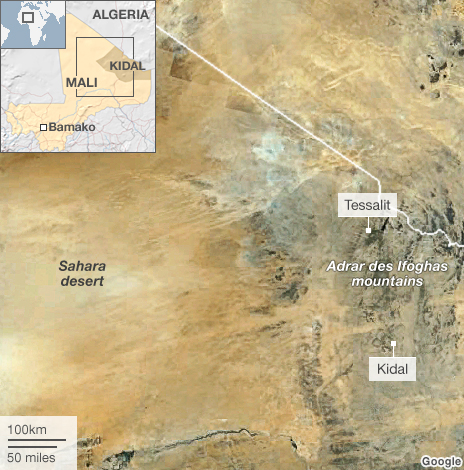

The Malian army’s humiliation was made complete when French and Chadian forces took the Tuareg stronghold of Kidal on February 9. Malian troops were deliberately excluded from the re-occupation force at the insistence of Tuareg separatist rebels and Tuareg Islamists who recently left Ansar al-Din. Units from these rebel groups, considered to be the enemy by Bamako and the Malian army, are now working alongside French forces while Malian troops are urged to keep out of Kidal. Colonel al-Hajj ag Gamou and his pro-Bamako Tuareg militia are the only Malian troops operating in Kidal, having come into northern Mali from Niger alongside Chadian and Nigérien troops. According to Ag Gamou: ““The French have to continue their mission until the threat is neutralised… and Mali’s army is able to control the whole country” (Radio France Internationale, February 15). When asked about the absence of Malian troops in Kidal, the Minister of Defense, General Camara, explained that “the Malian army cannot keep pace with the maneuvers of the French army… because we have an army reconstruction” (Le Républicain [Bamako], February 18).

The paratroopers of the 33rd Regiment insist they are ready to fight for Mali, but will do so only as a unit, declaring on January 31: “We are at the disposal of the nation which will make of us what she wants” (L’Indicateur du Renouveau [Bamako], February 14). Prime Minister Cissoko took to national TV on February 15 to announce that the 33rd would be “restructured” rather than disbanded. One company would act as instructors in Bamako while the other two companies would be sent to Gao and Timbuktu, where they would receive training before being deployed in active operations in northern Mali. These measures are scheduled to take place by March 1 “at the latest” (AFP, February 16).

Before Paris apparently mistook a probing effort by Islamist rebels as a full-fledged attack on the Malian capital and launched a massive military intervention in January, there was a general consensus in the international community that the inevitable military drive through northern Mali had to be preceded by a restructuring and retraining of the Malian military that included the removal of soldiers from the levers of power in Bamako. The hasty intervention has instead left elements of the Malian military still meddling in politics and many of its best troops as virtual prisoners in a military base outside Bamako. At the moment, there seems little possibility that Mali’s army will play anything more than a marginal role in the re-conquest of the north. If military success by the international forces in northern Mali is not accompanied by political restructuring and military reform, the ongoing intervention will likely have little long-term impact on regional security.

This article originally appeared in the February 22, 2013 issue of the Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor.

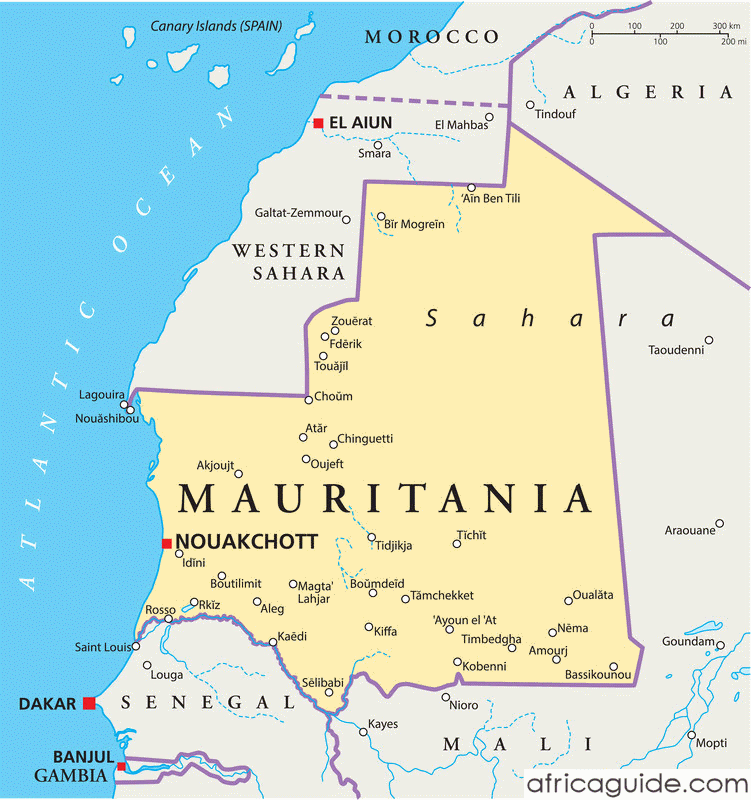

Abu Ayyub al-Mahdi (a.k.a. Ahmad Salim bin al-Hassan), an imprisoned Mauritanian Salafist, announced the creation of a new militant group, Ansar al-Shari’a in the Shanqiti [Mauritanian] Country, on February 12, the latest in a series of autonomous but ideologically sympathetic Ansar al-Shari’a groups to spring up across North Africa and the Middle East.

Abu Ayyub al-Mahdi (a.k.a. Ahmad Salim bin al-Hassan), an imprisoned Mauritanian Salafist, announced the creation of a new militant group, Ansar al-Shari’a in the Shanqiti [Mauritanian] Country, on February 12, the latest in a series of autonomous but ideologically sympathetic Ansar al-Shari’a groups to spring up across North Africa and the Middle East.