Andrew McGregor

February 8, 2013

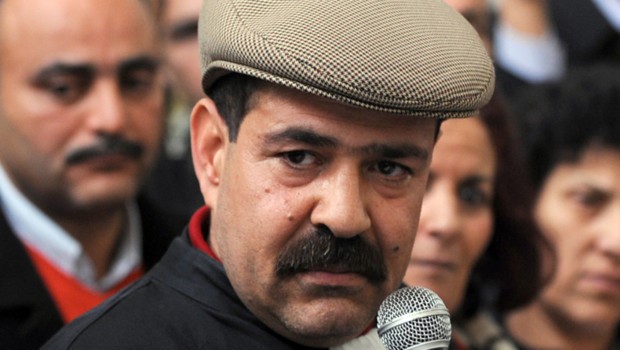

Growing tensions in Tunisia between that nation’s Islamist government, secular political forces and radical Salafists exploded on February 6 following the assassination of a leading Tunisian secularist politician, Chokri Belaid. Within hours, the Tunis headquarters of the ruling Islamist Ennahda party was set ablaze, thousands of protesters gathered outside the Interior Ministry demanding the fall of the regime and major protests erupted in cities across Tunisia (Reuters, February 6; Tunisia Live, February 6). Though the perpetrators have yet to be identified, popular suspicion has fallen on both the Salafists and Ennahda. Elements of both groups were accused by Belaid (a forceful critic of the government) of attacking a conference of Belaid’s Democratic Patriots party on February 2 (AFP, February 2). The murder took place in the midst of a political crisis generated by Ennadha’s need for a coalition government to remain in power but its unwillingness to share important cabinet posts (Agence Tunis Afrique, February 2; AFP, February 2).

Tunisia is also facing a growing jihadist movement within its borders. On February 1, Tunisia renewed its two-year-old state of emergency for another month in reaction to recent confrontations between security forces and armed jihadists seeking to create an Islamic state. Security was also stepped up with “special units” being posted at oil facilities in southern Tunisia in the aftermath of the In Aménas terrorist attack in neighboring Algeria.

According to Interior Minister Ali Larayedh, 16 militants were arrested in December after accumulating arms with the intention of imposing an Islamic state in Tunisia (al-Ahram [Cairo], January 29). The cell was tracked down in the mountainous pine forests of Jaball Chambi National Park in Kasserine governorate after a Tunisian National Guard patrol was attacked by gunmen near the Algerian border, with the loss of one NCO and four wounded guardsmen. The gunmen were identified as members of the Uqbah ibn Nafa’a group and were said to be equipped with arms, explosives, maps, communications equipment and uniforms (al-Hayat, January 22; Jeune Afrique, February 4, 2013; Tunis Afrique Presse, December 11, 2012; al-Watan [Algiers], January 30). [1]

According to a major pan-Arab daily, Tunisian jihadists are reported to be training in camps run by the Libyan Ansar al-Shari’a in the Abu Salim district of Tripoli, Zintan in Jabal al-Gharbi (western Libya) and Jabal al-Akhdar (eastern Libya) (al-Hayat, January 22). In Tunisia’s west, trafficking of all sorts has increased along the Algerian-Tunisian border since the Tunisian revolution two years ago. Border controls are much diminished with bribes or the threat of retaliation usually being enough to ensure smooth passage for smugglers. Algerian Prime Minister Abd al-Malik Sellal identified 11 Tunisians among the terrorists who seized the natural gas facilities at In Aménas in January (Tout sur l’Algérie, January 23).

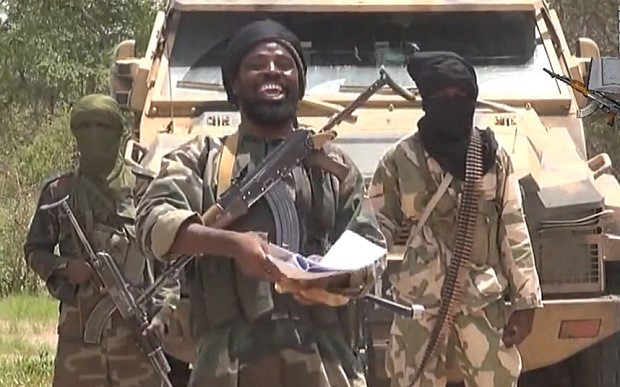

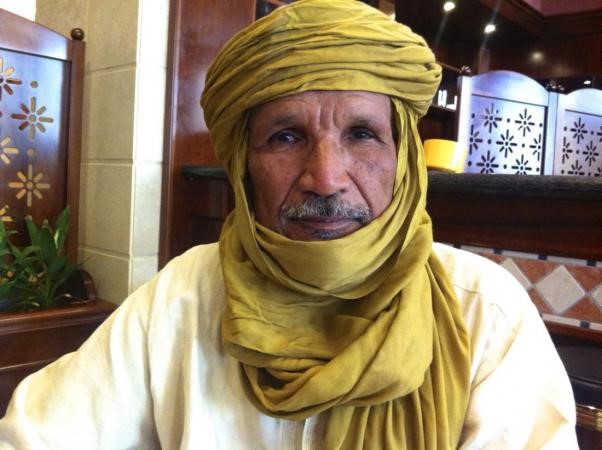

Tunisia’s Salafi-Jihadists received a declaration of support in late January from Sanda Ould Bouamama, the spokesman of the militant Ansar al-Din organization of northern Mali, now engaged in fighting with French-led international forces:

As for the brothers in Tunisia, we really cannot but stand up and say out loud: ‘May God salute you and make more people like you.’ Tunisia is restored to its nation and leads the rejection of aggression as it led the revolution. It also leads the rejection of the Crusader projects… France is gasping behind its economic greed and is drowning in its debt. All the French interests all over the world should be targeted. France came up with these interests to slaughter your brothers in Azawad [northern Mali] and others. All these interests should be targeted (al-Sharq al-Awsat, January 25).

Like their counterparts in Libya, Egypt, Somalia and elsewhere, the Salafists have launched a campaign against the “idolatry” of traditional Sufist Islam, largely by a series of fire-bomb attacks against over 40 Sufi shrines and mausoleums in Tunisia since the revolution. This campaign has stepped up recently, with the perpetrators seemingly emboldened by a systemic failure of security forces to prevent such attacks.

After trying unsuccessfully to persuade their fellow Tunisians to abstain from celebrating the Mawlid al-Nabi (the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday) in January, Salafist marked the occasion by torching the 300-year-old mausoleum of Sidi Muhammad al-Ghouth in the oasis town of Douz (site of a major firefight between militants and police in August, 2011), the mausoleum of Sidi Ali Ben Salem al-Hamma in Gabès and the mausoleum of Sidi Knaou in the small Berber town of New Matmata in southern Tunisia (Shems FM [Tunis], January 24; Webdo.tn, January 24). This was followed a few days later by an arson attack on the mausoleum of Sidi Boughanem in Kasserine governorate, a sparsely inhabited region in the Tunisian interior where Salafist militants appear to have set up operations (Shems FM [Tunis], January 31). Kasserine is useful as it borders Algeria, allowing the possibility of direct contact with Algerian militants of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. There are allegations that Libyan arms are now passing both ways across the border in this region (al-Hayat, January 22).

A blow was struck against both traditional Islam and a tourist industry that relies heavily on European visitors when Salafists destroyed the mausoleum of Sidi Bou Said on January 12 in the town named for him on the Tunisian coast. A famous artists’ colony entirely repainted in blue and white in the 1920s at the behest of artist and resident Baron Rodolphe d’Erlanger, Sidi Bou Said is a cornerstone of the Tunisian tourist industry. The famed mausoleum of 13th century Islamic saint Sidi Bou Said (a.k.a. Abu Said ibn Khalif ibn Yahya Ettamini al-Beji) was of special interest to historically-minded visitors due to its legendary association with Saint Louis (King Louis IX of France, 1214-1270), who died in Tunisia after a lifetime of crusading in the Middle East. Local Berber legend maintains that Louis IX adopted Islam and married a Berber princess before his eventual death in the town, though there is little in the historical record to support this legend. [2] A number of rare manuscripts containing the teachings of Sidi Abu Said were also destroyed in the fire (France24, January 18).

Such attacks have brought strong criticism from traditional Islamic leaders in Tunisia such as Mufti Uthman Batikh: “[The Salafists] accuse people of being infidels; they don’t accept dialogue. Such stiffness is what made people reject them. This is all a result of their ignorance of the reality and the history of Islam” (NPR, January 29).

Unexpectedly, fugitive Tunisian jihadist leader Abu Iyadh described those responsible for burning mausoleums and other shrines as “stupid,” saying that such monuments must first be “burned in the minds of the people before begin burned in reality,” an allusion to the need for religious education before undertaking such acts (Mosaique FM [Tunis], February 3; Tunisie Soir, n.d.). Abu Iyadh (a.k.a. Sayfallah bin Hussein), is the leader of the Tunisian Ansar al-Shari’a movement and is believed to have organized the September 14, 2012 attack on the U.S. embassy in Tunis in which four attackers were killed. The veteran jihadist fought in Afghanistan and was sentenced to 43 years in prison in Tunisia after being arrested and extradited by Turkish authorities in 2003. After receiving a presidential pardon from the new Islamist regime, Abu Iyadh dedicated himself to the furtherance of Salafism and Shari’a in Tunisia (for Abu Iyadh, see Militant Leadership Monitor, May 1, 2012). The Salafist leader claims to have no connection to the growing violence in Tunisia, saying the West only fears Ansar al-Shari’a “because of its charitable work.” Abu Iyadh also regrets the departure of young Salafi-Jihadists for the battlefields of Syria and Mali, as the young Salafists are needed at home (Mosaique FM [Tunis], February 3; Middle East Online, February 5).

Besides attacking concerts, bars and individuals on the street who are deemed to be wearing “un-Islamic” clothing, Tunisia’s Salafists have also staged anti-government rallies and hunger strikes designed to obtain the release of the roughly 900 Salafists detained for various acts of violence.

Another of Tunisia’s leading Salafist radicals is Shaykh al-Khatib al-idrissi, a blind Islamic scholar who advocates the return of a Caliphate in Ifriqiya (Tunisia) that will eventually extend to all the world’s Islamic communities. He rejects the participation of Salafist political fronts like Jabhat al-Islah in the political process, asserting that anything short of full and immediate implementation of Shari’a is unacceptable. According to Shaykh al-Khatib, “Today, it is the West that governs economically, politically, militarily and in the media, but everything is collapsing and Islam is strengthened. The economic crisis has weakened the West, so this [political] model is vanishing. It is then that the Caliphate reappears” (Le Figaro [Paris], May 31, 2012).

Notes

1. The group is named for Uqbah ibn Nafa’a al-Fihri, the 7th century Arab general of the Quraysh tribe who defeated Berbers and Byzantines to seize Ifriqiyah (modern Tunisia) for Islam. For the growth of radical Salafism in Tunisia, see Terrorism Monitor Brief, November 30, 2012.

2. See Afrodesia E. McCannon, “The King’s Two Lives: The Tunisian Legend of Saint Louis,” Journal of Folklore Research 43(1), January-April 2006, pp. 53-74.

This article first appeared in the February 8, 2013 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.