Andrew McGregor

Aberfoyle International Security

May 1, 2012

Growing violence between cattle herders and farmers in Africa’s sub-Saharan Sahel belt has fuelled militancy among the cattle-herding Fulani people, many of whom are beginning to form armed groups to defend their self-declared interests. The Fulani, most of whom are nomadic or semi-nomadic, are found in a wide sub-Saharan belt stretching from Guinea-Conakry and Mauritania in West Africa to Sudan, Cameroon and the Central African Republic to the east. The Fulani use a Niger-Congo language known variously as Pulaar or Fulfulde. Due to their wide dispersion across Africa, the Fulani are known by many names, including Fula, Fulbe and Peul.

A Fulani Herdsman (BBC)

A Fulani Herdsman (BBC)

The Fulani’s pursuit of a pastoral lifestyle at a time of increasing environmental pressures has frequently brought them into conflict with more sedentary communities. In northern Mali the Fulani herdsmen are often in conflict with the Tuareg and Arab nomads of the region and are closely associated with the Ganda Koy/Ganda Iso “self-defense” militias. In Sudan, President Omar al-Bashir has suggested that the long-standing Fulani community is composed of West Africans who have no right to vote in Sudan (Sudan Tribune, November 1, 2008).

In northern Ghana, the Fulani herders are regarded as foreign intruders who abduct women, engage in unregulated cross-border trade and destroy local agriculture. Northern farmers have appealed to the government for help in eliminating the “menace of alien Fulani herdsmen,” though they are not beyond taking matters into their own hands; in early January there were reports that local residents had burned down the shelters of over 100 Fulani families and looted all their cattle (Ghana Broadcasting Corporation, January 11, 2012; GhanaWeb, April 14, 2012).

In Nigeria the Fulani became closely tied to the Hausa following the invasion of the Hausa lands by Uthman Dan Fodio’s Fulani jihadists in 1804-1810. They are thus known as the Hausa-Fulani today, and represent nearly 30% of the population in Nigeria. Clashes between sedentary agricultural communities and the Fulani have become common (especially in those Nigerian states bordering Cameroon) as the Fulani have begun moving their herds into territories out of the traditional range of the herders. The situation closely resembles the movement of Arab herders in Darfur into agricultural lands maintained by indigenous African tribes that helped spark the Darfur crisis in 2003:

- In Nigeria’s Nasarawa State, some 18 people were killed in recent clashes between local residents and gunmen reported to be well-armed Fulani tribesmen dressed entirely in black, though the State’s governor expressed doubt over the participation of the Fulani in the attacks (Nigerian Tribune, April 7, 2012).

- In Benue State, over 3,600 Fulani nomads were forced to take refuge in temporary IDP camps in neighboring Cross River State after a series of clashes with local farmers. However, new problems arose when Fulani cattle began grazing on farmland in Cross River State (Nigerian Tribune, April 11, 2012; The Nation [Lagos], April 11, 2012).

- Six villages were reported to have been razed by men believed to be Fulani raiders in Taraba State on April 4. A small patrol of soldiers from the 93rd Battalion engaged a large body of raiders in the early hours of the morning, suffering the loss of two soldiers (Nation [Lagos], April 5, 2012; Leadership [Lagos], April 5, 2012).

The great Fulani jihad leaders of the 19th century appear to have provided the inspiration for a recently formed offshoot of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) known as Jamaat Tawhid wa’l-Jihad fi Garbi Afriqiya (Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa – MUJWA). With a leadership consisting of West African Muslims rather than North African Arabs, the movement has cited the examples of ‘Uthman Dan Fodio, al-Hajj ‘Umar Tal and Amadou Cheikou, whose massive armies fought animists, fellow Muslims and Christian imperialists alike to form their own short-lived empires in West Africa.

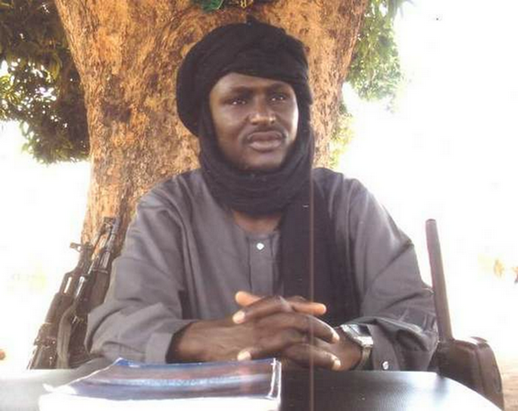

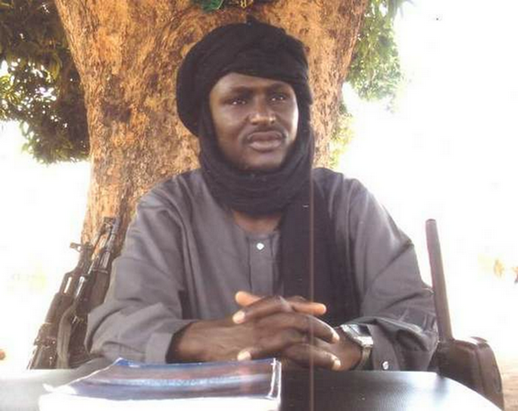

“General” Abdel Kader Baba Laddé

Operating from deep in the ungoverned bush of the northern part of the Central African Republic (CAR), a poorly educated Fulani tribesman from southern Chad leads a rebel movement of several hundred men that claims to be both a Fulani self-defense militia and an armed movement set on bringing democracy to Chad and the CAR. Led by the self-appointed “General” Abdel Kader Baba Laddé, the Front Populaire pour le Redressement (FPR) is regarded by many as little more than a bandit group with a political veneer despite its broad ambitions.

“General” Abdel Kader Baba Laddé

“General” Abdel Kader Baba Laddé

The 42-year-old Baba Laddé hails from the Mayo-Kebbi region of southwestern Chad, near the borders with Cameroon and Nigeria. A former non-commissioned officer in the Chadian army, Baba Laddé promoted himself to the rank of general after leaving the army and forming a rebel group to overthrow the government of President Idris Déby. Baba Laddé is not a man of minor ambitions, however, and in addition to overthrowing the leader of Chad he also proclaims his desire to unite all members of the scattered Fulani tribe from Mauritania to the Sudan (Jeune Afrique, December 26, 2011).

“General” Laddé’s lightly armed militia was unable to maintain a presence in Chad in the face of a government offensive in 2008 and crossed the border into the northern regions of the CAR, a lawless area that has become home to all manner of bandits, rebels and coupeurs de routes (highwaymen). Baba Laddé eventually made his headquarters in the market town of Kaga-Bondoro, 245 km north of the capital of Bangui. Lying just south of the border with Chad, the wilds of the Ubangi-Shari region (as the CAR was known during the French colonial period) have traditionally provided shelter to a variety of Chadian renegades. Parts of this region were severely depopulated by slavers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a calamity from which the area has never completely recovered.

A recent petition of leading citizens of the affected areas demanding government action against the “exactions” of Baba Laddé and his inclusion in an international list of war criminals cited various crimes carried out by the FPR, including looting, rape, mutilation, the displacement of thousands of people, the assassination of international aid staff and the kidnapping of children for use as child-soldiers. The movement has also been accused of being sympathetic to the goals of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). [1]

The Central African Republic

The Central African Republic

Baba Laddé’s sympathizers suggest that, unlike the other marauding rebel/bandit groups in the CAR, the FPR is popular with local people due to its dedication to peace and security but has fallen victim to a malevolent press allegedly in the pay of CAR President François Bozize that hold Baba Laddé “responsible for all the ills of the CAR.” [2] When asked to respond to claims that the “General” was keeping order in the areas under his control, the President replied: “But who authorized him to do so? Who asked him?” (Jeune Afrique, February 9). In reality the FPR raises much of its funds by “taxing” Fulani herders driving their cattle through the northern CAR (Centrafrique-Presse, December 19, 2011). Extortion of local communities, cattle theft and revenues from raiding provide most of the rest (IRIN, January 12, 2012). As well as recruiting from the Fulani community, the FPR welcomes local bandits and former members of the dozen or so rebel movements operating in the northern CAR. Weapons are acquired from across the Sudan border in Darfur, where they are found in abundance after years of warfare. N’Djamena has tried to avoid giving the FPR any political legitimacy – the Chadian Ministry of Information and Communications recently asserted that there are no Chadian rebels in the CAR, only “criminals and zaraguinas [highway robbers]” (AFP, February 14, 2012).

Deportation to Chad

In September, 2009 Baba Laddé agreed to talks with Chadian government representatives in Bangui under the mediation of the CAR government. The FPR leader appeared ready to sign on to the Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration process (DDR) process already signed on to by a number of rebel movements, but first demanded a personal apology from the Chadian president to Mbororo (the Fulani sub-group to which he belongs) cattle herders for attacks allegedly carried out by Chadian military forces. Baba Laddé also suggested it “would be judicious” for the Chadian president to provide the FPR with logistics, food and financial compensation to prepare the group for their return to Chad (Le Confident [Bangui], September 22, 2009). Supposedly under the protection of MICOPAX peacekeepers during negotiations in the CAR capital, the FPR leader disappeared on October 9, 2009 on his way to the CAR Defense Ministry. [3]

Angered by clashes between the FPR and Chadian forces along the CAR’s northern border, the CAR government had apparently decided to solve the Baba Laddé’ problem by quietly extraditing him to Chad in an operation allegedly planned by Colonel Mila Allafi Tanga, the Chadian military attaché at the Chadian Embassy in Bangui (Centrafrique-Presse, December 19, 2011, Le Confident [Bangui], October 13, 2012; October 15, 2012; October 22, 2012). MICOPAX claimed it had no involvement in the abduction and extradition and later sent a mission to N’Djamena to ascertain his location and condition (Le Confident [Bangui], November 15).

The Front Islamique Tchadien (FIT – Chadian Islamic Front), an insurgent group that also promotes Fulani solidarity, threatened to launch a jihad against Bangui unless Baba Laddé was released (L’Hirondelle [Bangui], October 13, 2009; for FIT, see Terrorism Focus Brief, July 16, 2008). FIT also claims to have sent some of its members to the CAR to organize “vigilante” groups amongst the Chadian herders “under threat” in the northern CAR. [4]

In November, 2009 panic was created in the Kaga Bandoro region when the FPR was attacked by Jean-Jacques Démafouth’s Armée Populaire pour la Restauration de la Démocratie (APRD), a much stronger militia whose area of operations overlaps that of the FPR in the Kaga-Bondoro region (Le Confident [Bangui], November 3, 2009). The APRD has since declared that it would only join the DDR process if the FPR returned to Chad (IRIN, January 12, 2012).

Baba Laddé was not seen again until August, 2010 when he surfaced in Cameroon, claiming to have escaped ten months of torture in N’Djamena. Baba Laddé then disappeared again in November, 2010, turning up in the CAR in January, 2011 (AFP, April 19, 2011).

The CAR – A Permanent State of Instability

A CAR-based UN representative, Margaret Vogt, told the UN Security Council last December that the CAR was “on the brink of disaster” due to its inability to find $22 million to pursue the DDR process. Vogt also demanded that Baba Laddé be held accountable for his human rights violations against the people of the CAR (UN News Center, December 14, 2011). It has been alleged locally that Baba Laddé has supporters within the CAR government, most notably Minister for Livestock Youssoufa Yerima Mandjo, a fellow Fulani (Centrafrique-Presse, December 19, 2011; January 6, 2012).

Baba Laddé signed a peace agreement with Chadian representatives in Bangui on June 13, 2011, telling national radio: “I think we have put a final end to the hostilities” (AFP, June 14, 2011). However, by this time it appeared that Baba Laddé had begun to lose interest in Chad as expanding his influence in the CAR became more appealing than a return to his homeland (Centrafrique Matin [Bangui], December 23, 2011).

Abdoulaye Miskine (3rd from left) with FDPC fighters (FDPC/AFP)

Abdoulaye Miskine (3rd from left) with FDPC fighters (FDPC/AFP)

Baba Laddé’s forces clashed in January, 2012 with the Front Démocratique du People Centrafricaine (FDPC) led by Abdoulaye Miskine (real name Martin Koumta-Madji), another Chadian adventurer who once provided security for former CAR President Ange-Felix Patassé, overthrown in 2003 by Bozizé, his former army chief-of-staff. In November, 2008 Miskine’s men ambushed a Forces Armées Centrafricaines (FACA) patrol, killing nine soldiers. President Bozizé has close ties with the Déby regime and came to power with the assistance of the Chadian military. Chadians are well represented in the Garde Républicaine (responsible for the president’s security), the only reasonably equipped branch of the security forces. The Guard is otherwise made up of members of Bozizé’s Gbaya tribe, who protect the president from the army, which is largely composed of members of the Yakoma tribe. Since the army is only sporadically paid and is generally alienated from its own commanders, it tends to act as yet another predatory force rather than a savior when dealing with civilians outside the capital, the only region that can honestly be said to be under FACA’s control. France maintains a small garrison of 150 to 200 men in Bangui that can be quickly supplemented by the Force d’Action Rapide to protect French citizens and interests in times of crisis.

Chad and the CAR began joint operations against the FPR in the region north of Kaga Bandaro in late January (Journal de Bangui, January 24, 2012). Chadian helicopters worked in concert with ground forces of both nations in attempting a pincer movement to trap and eliminate Baba Laddé’s group, though this strategy appears to have failed due to the movement’s habit of dispersing itself in small groups of fighters over a large area. Nonetheless, heavy fighting was reported and the joint forces claimed to have smashed the FPR’s command post north of Kaga Bandaro (AFP, January 26, 2012; Journal de Bangui, January 30, 2012).

Fulani Herdsmen Are Typically Armed These Days

Fulani Herdsmen Are Typically Armed These Days

In response to the joint offensive against the FPR, Laddé declared that he considered the CAR’s position to be “a declaration of war by [President] François Bozizé” and announced the formation of a new anti-Bozizé political movement, the Parti Pour la Justice et le Développement (PJD), with a military wing going by the name of the Forces Armées Révolutionnaires de Centrafrique (FARCA) (RFI, January 28, 2012). According to the founding communiqué, PJD-FARCA was in discussions with three other movements to overthrow the Bozizé “dictatorship,” these being the aforementioned APRD, the Convention des Patriotes pour la Justice et al Paix (CPJP) and the Union des Forces pour la Démocratie et le Rassemblement (UFDR). Some of these groups, however, have signed a ceasefire agreement with Bangui and none have reported forming an alliance with the FPR or PJD-FARCA.

The statement also called on all members of the Central African armed forces to desert and join FARCA (Le Jour [Conakry], January 27, 2012). In one of his grander moments, Baba Laddé also suggested an alliance between the Fulani, the Tuareg, the ethnic-Somali rebels of Ethiopia’s Ogaden region, the Sahrawi Polisario and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) (Jeune Afrique, December 26, 2011). On February 14, the FPR announced it had captured 27 FACA soldiers and added that it was sending a detachment of FPR fighters to reinforce rebel groups in the mainly Tubu Tibesti region of northern Chad, though there is no evidence this actually happened. [5]

In Defense of Rebellion

On March 12, Baba Laddé issued an extraordinary “Appeal to the Defenders of Human Rights,” a document that revealed much of the inflated self-view of the “General,” beginning with the regal tone of the opening line: “I am the General Baba Laddé and I have decided to take up my pen to inform the world of two very important things.” [6] Laddé continued with an appeal for human rights organizations to secure the release of the “many members of my family and families of my fighters” who were arrested in the CAR and Chad. Baba Laddé then announced that the FPR and PJF-FARCA have decided to launch a call for peace negotiations under the auspices of the UN. The proposed international peace conference would gather representatives of “the CAR, Chad, all political and military movements of Chad and Central Africa, the legal opposition parties, representatives of neighboring states of both countries, including Libya, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan and Sudan, as well as representatives of states conducting military operations in both countries: France, the United States and Uganda.” Representative of Darfur’s Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) and the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) could also attend, provided the latter dismissed Joseph Kony and other leaders wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC). Baba Laddé warned his movement “will be obliged to resume the armed struggle to establish democracy” in Chad and the CAR should it not receive a positive reply to this proposal by May 1.

Baba Laddé was also disturbed by remarks made in a March 2012 interview by former Burundian president and current African Union mediator Pierre Buyoya, who expressed surprise that a well-known “bandit and coupeur de route” like Baba Laddé now had political policies and suggested that the FPR leader might be manipulated by external forces (Jeune Afrique, March 16, 2012). In his response, Baba Laddé asked if “a Black, an African cannot have political ideas without being manipulated by an external power? Or is this [just] Chadians or Fulani who cannot have an opinion? Or is it because I’m not from a middle-class [background] and have not done studies abroad? And yes, a poor Chadian Fulani may have a political opinion” (Press-FPR, March 21, 2012).

In the same statement, Baba Laddé then went on to describe his “political discourse,” a far-ranging Qaddafi-esque platform that included democracy for Chad and the CAR, the abandonment of a “genocide” against Nigerians under the guise of fighting Boko Haram, peace negotiations between all parties in Mali, justice for “atrocities” against the Fulani in Guinea-Conakry, equality between blacks and Moors in Mauritania and between Arabs and Tubu in Libya, condemnation of the “crimes” of Bashar Assad, Vladimir Putin and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in Syria, support for the independence of the Angolan province of Cabinda, an end to torture in Ethiopia and a request for Israel to cease bombing in Gaza. The FPR commander went on to express his wish to fight Joseph Kony’s LRA (which operates in the southern CAR), an oft-expressed desire that is never transformed into action but serves to deflect attention from the activities of his own men in the northern CAR. Baba Laddé wrapped up his message by informing his opponents that: “Despite the threats, the FPR and the PJD will continue to fight the dictatorship of Déby and Bozizé. And if you want peace, you must negotiate with us, the lower people.”

Notes

1 “Collectif á Lingbi Awe Baba Laddé Tous Contre les Exactions de Baba Ladde en Centrafrique,” January 5, 2012, published by Centrafrique Press, January 16, 2012.

2 http://makaila.over-blog.com/article-bozize-et-deby-ont-conspire-contre-le-fpr-il-va-de-notre-interet-de-tendre-la-main-aux-groupes-reb-98342951.html.

3 The Mission de consolidation de la paix en République Centrafricaine (MICOPAX) is a peacekeeping operation led by the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), formed by Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, the CAR, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Congo-Brazzaville and São Tomé and Príncipe. With a strength of just over 500 troops and training from French military advisers, MICOPAX attempts to restore security to regions of the northwest CAR plagued by roving zaraguinas.

4 “Protégeons les tchadiens en RCA,” April 10, 2010. http://frontislamiquetchadien.blogspot.ca/2010/04/protegeons-les-tchadiens-en-rca.html ,

5 Press Release, PJD-FARCA, Cellule de Communication du Front Populaire pour le Redressement (FPR), ChariNews, February 14, 2012.

6. http://makaila.over-blog.com/article-rca-tchad-l-appel-du-general-baba-ladde-101447598.html

Remains of the Shrine of Shaykh Zuwayid after its Destruction (Reuters/Asmaa Waguih)

Remains of the Shrine of Shaykh Zuwayid after its Destruction (Reuters/Asmaa Waguih)