Andrew McGregor

January 8, 2018

The career of Sulayman Arcua Minawi (better known as “Minni Minawi”) is the story of how a primary school teacher in a remote corner of northern Africa parlayed an ability to read and write and a previously hidden penchant for ruthlessness into his appointment in October 2017 as chairman of the Sudan Revolutionary Front (RSF), a coalition of Sudan’s armed opposition movements. Though widely disliked and lacking any semblance of the charisma usually found in revolutionary leaders, Minawi has nonetheless survived nearly two decades as a rebel leader in the brutal and unforgiving conflict being played out in Darfur.

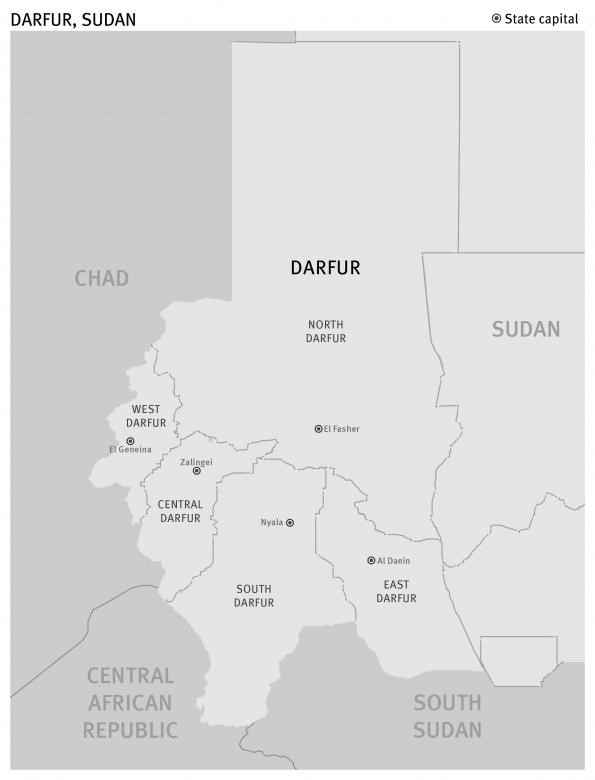

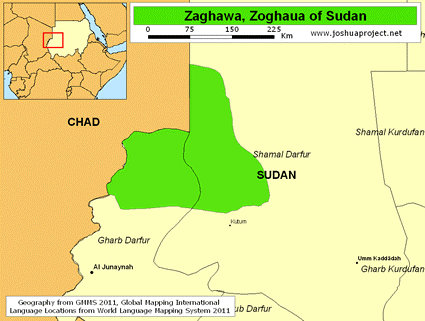

Born in or near the North Darfur town of Kutum on December 12, 1968, Minawi is a member of the Ila Digen clan of the Wogi sub-group of the Zaghawa, a desert-dwelling ethnic group speaking a Nilo-Saharan language but with broad knowledge of Arabic and French.

Prior to the opening of the Darfur rebellion, Minawi was a primary school teacher with a secondary school education but no political or military experience. [1] He spent much of the 1990s away from Darfur working as a trader in neighboring countries and learned English in Nigeria before returning home in 2001. After joining a Zaghawa self-defense militia, Minawi’s literacy helped a rapid ascent to important administrative positions, though a strong dislike for intellectuals and resentment of more experienced individuals has characterized much of his career. [2]

The Zaghawa

The Zaghawa, who call themselves “Beri,” are found in some of the most inhospitable regions of northern Sudan, northern Chad and southern Libya. Estimates of their total numbers range from 225,000 to 450,000, making them a small minority in each region.

The traditionally nomadic Zaghawa, divided by colonial borders imposed in the early 20th century, belong to one of three sub-groups; the Zaghawa Kobé, mostly in northern Chad with smaller numbers in northern Darfur; the Bideyat (close to the Tubu ethnic group) who are also found on both sides of the border, and the Zaghawa Wogi, most of whom live in northern Darfur. Each of these sub-groups is in turn divided in to a number of clans with little political cohesion. The broad range of northern territory inhabited by the Zaghawa is known as “Dar Zaghawa,” the Zaghawa homeland.

The traditionally nomadic Zaghawa, divided by colonial borders imposed in the early 20th century, belong to one of three sub-groups; the Zaghawa Kobé, mostly in northern Chad with smaller numbers in northern Darfur; the Bideyat (close to the Tubu ethnic group) who are also found on both sides of the border, and the Zaghawa Wogi, most of whom live in northern Darfur. Each of these sub-groups is in turn divided in to a number of clans with little political cohesion. The broad range of northern territory inhabited by the Zaghawa is known as “Dar Zaghawa,” the Zaghawa homeland.

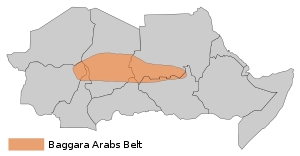

An early recognition of the value of education and success in commerce at home and in Libya and the Gulf region have given the Darfur Zaghawa an influence disproportionate to their numbers in Sudan, a development that has led some Arabs and other non-Zaghawa groups to fear the Zaghawa seek to create a “Greater Dar Zaghawa” (Dar Zaghawa al-kubra) at their expense. The recent geographical dispersal of the group and the establishment of powerful Zaghawa-led armed groups have only fueled these suspicions. [3]

Chad’s president since 1990, Idriss Déby Itno, is a Zaghawa of the Bilia clan of the Bideyat group and has played an influential role in the Zaghawa rebellion in Darfur. Many of Déby’s inner circle, as well as the leaders of the armed opposition, are Bideyat. In December 2010, Déby dismissed his half-brother Timan as sultan of the Bilia and assumed the post himself (Jeune Afrique, December 27, 2010).

The Darfur Zaghawa became increasingly militarized by their participation in Chad’s civil conflict in the 1980s and by their creation of self-defense militias during clashes with government supported Arab groups in northern Darfur in the 1990s and early 2000s. Weapons were frequently made available by their kinsmen in the Chadian and Libyan militaries.

The Sudan Liberation Front

In June 2002, Minawi became a founding member of the short-lived Darfur Revolutionary Front (DLF) led by Abd al-Wahid al-Nur, a Fur lawyer and former member of both the Communist Party of Sudan and the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A), a largely but not exclusively southern-based revolutionary movement determined to break the hold of Sudan’s Arab riverine tribes (the Sha’iqiya, the Danagla and the Ja’aliyin) over Sudan’s central government. The group’s first military action occurred in February 2003 when it temporarily seized the town of Gulu in the mountainous Jabal Marra region, homeland of the Fur.

Shortly afterward, al-Nur changed the name of the DLF to the Sudanese Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A), adopting the dual political-military structure of the SPLM/A. The movement was composed mainly by the non-Arab Fur, Zaghawa and Masalit groups.

The SLM/A transformed a minor rebellion in an obscure region to front-page news with a spectacularly effective April 25, 2003 assault on the military airport at al-Fashir, the Darfur capital. The operation was carried out jointly with the Zaghawa-led Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), a group with Islamist sympathies and a national focus.

On the same day as the airport attack, the SLM/A engaged Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) troops in Minawi’s hometown of Kutum, where they seized four tanks. Further engagements in Zaghawa territory followed, with the late May destruction of an SAF battalion at Kutum, a mid-July attack on Tine in Dar Zaghawa that killed 250 troops, and the capture of Kutum on August 1, 2003. [4] The Zaghawa initially benefited from their familiarity with the highly mobile tactics employed in Chad but a strong government counter-offensive sent Minawi fleeing for safety in Libya. His attempts to control the rebellion from abroad led to dissent within his own movement. [5]

As secretary-general of the SLM/A, Minawi released the group’s manifesto on March 14, 2003. The “Political Declaration” of the SLM/A called for a secular and “united democratic Sudan” with “full acknowledgement of Sudan’s ethnic, cultural, social and political diversity. [6] The similarity of the declaration to the principles of John Garang’s SPLM/A was no coincidence, as the document was largely written by SPLM advisors. [7]

Minawi and the Formation of the SLM/A-MM

Minawi attempted to seize control of the SLM/A at the rebels’ October 2005 Haskanita Conference. Methods that included having opponents beaten led to a split in the movement, with Minawi leading what came to be known as the SLM/A-Minni Minawi (SLM/A-MM).

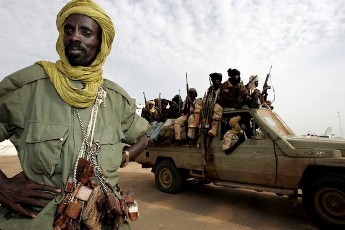

Fighters of the SLM/A-MM (AFP)

Fighters of the SLM/A-MM (AFP)

Minawi also began to clash with JEM, which accused him of partnering with Khartoum and Idriss Déby’s Zaghawa-dominated government in Chad to eliminate JEM in return for cash, a leadership role in Darfur and a sultanate for his Ila Digen sub-clan. [8] The Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) was largely Zaghawa Kobé while Minawi’s SLM/A-MM was largely Zaghawa Wogi. By this time the conflict in Darfur was becoming intertwined with the struggle for power between various Zaghawa clans in Chad.

Abuja Agreement and Government Member

The turning point in Minawi’s career was his decision to become the lone rebel commander to sign the Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA, also known as the “Abuja Agreement”) with the Khartoum government. When he signed the pact on May 5, 2006, he alienated not only other rebel commanders who refused to sign, but also many in his own movement.

Minawi, according to the agreement, was made special assistant to President Omar al-Bashir and chairperson of the Transitional Darfur Regional Authority on August 5, 2006. Many members of the SLM/A-MM began to abandon the movement for other rebel groups, reducing the movement mostly to members of Minawai’s Ila Digen clan. [9]

A month after signing the deal, Minawi returned to Darfur and began launching attacks on his former allies in the SLM/A-AW. Fifteen men of the latter group were kidnapped northwest of al-Fashir and were tortured by Minawi’s men for refusing to sign the peace agreement. Eleven were released and their signs of torture documented by AU peacekeepers. Among those held was the elderly Zaghawa humanitarian coordinator Sulayman Adam Jamous (Independent, June 7, 2006). As Minawi’s men began to gain a reputation for such excesses they became known to some Darfuris as “Janjaweed Two” (IRIN, August 4, 2006). The result was another wave of defections from Minawi’s movement, even including members of his Ila Digen clan. [10] Battlefield defeats followed, with the loss of many of the weapons supplied to Minawi’s fighters by the SAF.

In early July 2006, Minawi’s men were accused of mass murder and rape in the area around the town of Korma, with the attackers telling their victims they were being punished for opposing the DPA. The SLM/A-MM gunmen were allegedly supported by units of Janjaweed and the SAF. [11] Nonetheless, Minawi travelled to Washington for a meeting with President George W. Bush later that month (npr.org, July 28, 2006).

By September, there were reports of Zaghawa herdsmen attacking Fur villages supported by Minawi’s fighters. The attacks caused flight into IDP camps around AU bases where armed SLM/A-MM fighters extorted money and carried out kidnappings for ransom (IRIN, September 5, 2006). Representatives of the movement blamed UN reports of rape and executions on biased UN observers. [12]

While in Cairo in February 2009 for talks with President Mubarak and top Arab League officials, Minawi acknowledged the Abuja agreement had failed due to its failure to include all the rebel factions. Minawi also claimed to have asked for Egypt’s assistance as a mediator due to its knowledge of the Darfur situation, but his approach did not bear fruit (al-Ahram Weekly, February 19-25, 2009).

General Ismat Abd al-Rahman Zine al-Abdin

General Ismat Abd al-Rahman Zine al-Abdin

The tensions between Minawi’s men and government security forces led by General Ismat Abd al-Rahman Zine al-Abdin exploded on March 28, 2007, when clashes broke out between the Darfuris and security forces surrounding the SLMA/A-MM office in Omdurman, leaving at least eight of Minawi’s men and two policemen dead. Over 90 of Minawi’s followers were arrested in the incident, during which the movement claimed government forces tore down the SLM/A-MM flag and confiscated computers and documents (Sudan Tribune, March 25, 2007).

Despite friction with the Khartoum government, Minawi was still regarded abroad as sufficiently influential to be invited to Cairo by the Arab League in February 2009, where he participated in talks with Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, intelligence chief Major General Umar Sulayman, Field Marshal Muhammad Hussein Tantawi and Foreign Minister Ahmad Abu al-Gheit. During his visit, Minawi met with U.S. diplomatic officials. The U.S. officials were unimpressed with Minawi, concluding that he “did not appear to have a vision for the future of Darfur, and was vague about the future of peace talks, his role in Sudan, the future of the GOS, and even the opening of a SLA office in Cairo.” [13]

In January 2009, Minawi’s forces were driven out of the South Darfur town of Muhajariya by their JEM rivals. Minawi had taken the town (largely Birgid) from JEM in 2005, when it became the largest settlement under Minawi’s control. The SLM/A-MM had held the town through repeated attacks by Birgid, Tunjur and Janjaweed fighters. [14] JEM’s re-conquest was short-lived, as Birgid and SAF forces arrived to expel the town’s transplanted Zaghawa population (IRIN, January 28, 2009; al-Jazeera, January 24, 2009; BBC, February 5, 2009; Los Angeles Times, March 21, 2009).

Leaving the Government of Sudan

In an interview at his Khartoum residence with American law professor Rebecca Hamilton three years after signing the DPA, Minawi confided, “I can see the president any time I want. But he doesn’t trust me – and after three years here, I don’t trust him.” [15]

Despite the election of several SLM-MM members in the April 2010 general elections, Minawi was dropped from his position as fourth vice-president. [16] Minawi resigned from the government, moved to Juba (capital of South Sudan) and returned to the armed opposition. The GoS declared that Minawi was now “an enemy” of the Sudanese state and launched a new campaign against Zaghawa fighters and civilians in which Birgid and Tunjur militias were recruited and armed by the state. The campaign soon degenerated into a brutal tribal conflict with little political direction (al-Jazeera, December 13, 2010). [17]

The SLM/A-MM was not a signatory to the Qatar-sponsored Doha Document for Peace in Darfur (DDPD), signed July 14, 2011 by the Liberation and Justice Movement (LJM), a coalition of ten Darfur rebel movements. The agreement thus replicated the weakness of the earlier Abuja Agreement in not including all major rebel groups. Some Zaghawa Wogi abandoned the LJM to join Minawi’s movement or strike out on their own. [18]

By September 11, 2011, the SLM/A-MM was functioning as four separate units; one on the Sudan-Libya border, one in eastern Jabal Marra; one in northern Bahr al-Ghazal (South Sudan); and another in North Darfur. [19]

After his collaboration with the Khartoum government, Minawi had little credibility left in Darfur. In the first months of 2014, a much-weakened SLM/A-MM came under heavy attacks from the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a restructuring of the notorious Janjaweed intended to bring the Arab militias under the control of Sudan’s National Intelligence and Security Service. [20]

The SLM/A-MM Goes Mercenary

Under relentless pressure from the RSF and SAF, Minawi’s movement split, with one group heading south to take refuge in South Sudan while the greater part (like JEM) headed north to Libya’s southern Fezzan region. Arriving in March 2015, they began to operate as mercenaries, working for Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) or rival Islamist militias based in Misrata according to who offered more cash or arms. On this basis Minawi’s fighters took part in the LNA campaign to take control of the Sidra and Ras Lanuf oil terminals on Libya’s Mediterranean coast.

In a March 2016 interview, Minawi claimed Islamic State forces were hosted by the Khartoum government in Kutum and South Darfur, where extremists had allegedly gathered from Mali, Chad, Libya, Egypt and the Central African Republic (CAR). He went on to claim, without evidence, that the Sudanese government was responsible for terrorism in Libya and had a hand in the creation of the Islamic State, Boko Haram, al-Qaeda and the Islamic Séléka movement in the CAR. [21]

Return to Darfur

By early 2017, many of Minawi’s commanders and fighters were drifting back to Darfur, complaining that the movement’s leadership was withholding payments. The rest of the movement followed in May, intending to link up with the allied SLM/A-Transitional Council (SLM/A-TC, led by Nimr Abd al-Rahman) and SLM/A-MM fighters returning to Darfur from South Sudan.

The rendezvous was intercepted by RSF and SAF forces in the Kutum region and a fierce four-day battle followed in which the rebels were defeated. Nimr Abd al-Rahman, SLM/A-MM chief-of-staff Major General Juma Mundi Issa and Minawi’s military spokesman, Ahmad Hussein Mustafa, were captured. Other prisoners were reported to have been immediately executed by the NISS but this was denied by the RSF (Radio Dabanga, May 23; Sudan Tribune, May 23; Sudan Tribune, May 24; Anadolu Agency, May 23). The RSF claimed to have pursued the rebels along the upper Wadi Howar into Chad while others were reported to have fled towards Libya (Sudan Tribune, May 29; Radio Dabanga, May 21).

After the confrontation, Minawi declared: “The brutal regime of the National Congress (Party), as usual, mobilized the Rapid Support Forces militias in a desperate attempt to hit the SLM in its strongholds and impose peace through the barrel of the gun.” He added that a “cessation of hostilities” was required to contain the humanitarian disaster caused by the regime’s aggression on unarmed civilians” (Middle East Observer, May 28, 2017).

Undeterred, Minawi’s unlikely progress through rebel ranks continued with his surprising election as chairman of the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF- Al-Jabhat al-Thawriyat al-Sudan) on October 13, 2017. The SRF was formed in November 2011 as a coalition of Sudanese rebel movements. It was essentially a response to the July 2011 independence of South Sudan, which compelled a realignment of the remaining Sudanese opposition groups, including two divisions of the SPLA that continued to operate in (north) Sudan.

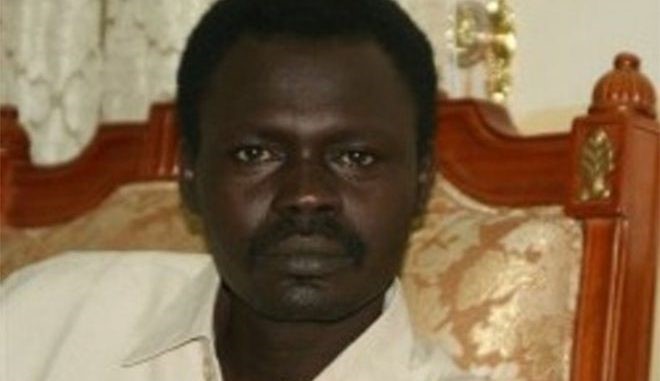

SLM/A-MM Leader Minni Minawi (Middle East Observer)

SLM/A-MM Leader Minni Minawi (Middle East Observer)

Conclusion

The battlefield defeat in May constituted a major setback for Minawi’s efforts to re-establish himself as a force in Darfur. Minawi’s movement continues to have little appeal beyond his Zaghawa Wogi base and his past behavior works against building a multi-tribal movement or effective leadership of the SRF. In fact, the record of assassinations, looting, theft of livestock and rape associated with the SLM/A-MM has succeeded in alienating Darfur’s Zaghawa population from their neighbors, who now regard Zaghawa migration from the deteriorating environmental conditions of their northern homeland with suspicion and resentment.

Notes

- “Sudan Liberation Army-Minni Minawi (SLA-MM),” Small Arms Survey, September 6, 2011, http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/fileadmin/docs/facts-figures/sudan/darfur/armed-groups/opposition/HSBA-Armed-Groups-SLA-MM.pdf

- Julie Flint, “Darfur’s Armed Movements,” in: Alex de Waal (ed.), War in Darfur and the Search for Peace, Harvard, 2007, p.110.

- Jerome Tubiana, “Land and Power: the Case of the Zaghawa,” African Arguments, May 28, 2008, http://africanarguments.org/2008/05/28/land-and-power-the-case-of-the-zaghawa/

- Robert O. Collins, “Disaster in Darfur,” in: Samuel Totten and Eric Markusen (eds), Genocide in Darfur: Investigating the Atrocities in the Sudan, Routledge, 2006, pp. 9-10.

- Julie Flint, op cit, pp.154-155.

- Salah M. Hassan and Carina E. Ray (eds), Darfur and the Crisis of Governance in Sudan: A Critical Reader, Cornell University Press, 2009, Appendix B.

- Julie Flint and Alex de Waal: Darfur: A New History of a Long War, London, 2008, p.91.

- Roland Marchal, “The Unseen Regional Implications of the Crisis in Darfur,” in: Alex de Waal (ed.), War in Darfur and the Search for Peace, Harvard, 2007, p.193.

- Abdul-Jabbar Fadul and Victor Tanner: “Darfur after Abuja: A View from the Ground,” in: Alex de Waal (ed.), War in Darfur and the Search for Peace, Harvard, 2007, p.289; Jerome Tubiana, “Land and Power: the Case of the Zaghawa,” African Arguments, May 28, 2008, http://africanarguments.org/2008/05/28/land-and-power-the-case-of-the-zaghawa/

- Julie Flint, op cit, p.160.

- “Korma: Yet more attacks on civilians,” Amnesty International, July 30, 2006, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr54/026/2006/en/

- Wikileaks: “Darfur: Update on Korma Attacks and Rape Allegations,” U.S. State Department Cable 06KHARTOUM, July 11, 2006, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KHARTOUM1637_a.html

- Wikileaks: “Darfur Leader Minni Minawi’s Visit to Cairo,” U.S. State Department Cable 09CAIRO339, February 24, 2009, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/wikileaks-files/egypt-wikileaks-cables/8327046/DARFUR-LEADER-MINNI-MINAWIS-VISIT-TO-CAIRO.html

- Mutasim Bashir Ali Hadi, “Power-sharing in Southeast Darfur: Local Translations of an International Model,” in Travelling Models in African Conflict Management: Translating Technologies of Social Ordering, Brill, 2014, pp.131-33.

- Rebecca Hamilton: Fighting for Darfur: Public Action and the Struggle to Stop Genocide, St. Martin’s Press, Feb 1, 2011, p.95.

- Small Arms Survey, op cit, September 6, 2011.

- A description of the conflict can be found in: Claudio Gramizzi and Jérôme Tubiana, “Forgotten Darfur: New Tactics and Old Players,” Small Arms Survey, 2012, p.15, http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/fileadmin/docs/working-papers/HSBA-WP-28-Forgotten-Darfur.pdf

- Ibid, p.15.

- Small Arms Survey, op cit, September 6, 2011.

- For the RSF, see: Andrew McGregor, “Khartoum Struggles to Control its Controversial “Rapid Support Forces,” Terrorism Monitor, May 30, 2014, https://jamestown.org/brief/briefs-43/

- Anadolu Agency Video, March 22, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/14310874716/videos/10154053104449717/