Andrew McGregor

Jamestown Foundation, June 2008

INTRODUCTION

The Turkish Armed Forces (Turk Silahli Kuvvetleri – TSK) consists of an army, navy and air force of considerable size and power. The Turkish Coast Guard and the paramilitary Gendarmerie (Jandarma – responsible for security in rural areas) both come under the command of the Ministry of the Interior but work closely with the TSK. In wartime both organizations would come under the command of the Ministry of Defense.

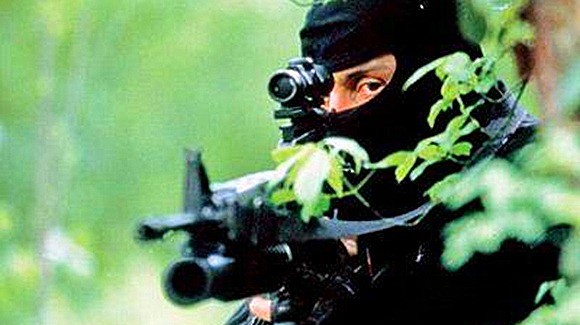

Turkish Special Forces in Northern Iraq (Hurriyet)

Turkish Special Forces in Northern Iraq (Hurriyet)

Under General Yasar Buyukanit (who took command of the armed forces as Chief of Staff in August, 2006), the Turkish General Staff (TGS) has intensified its program of military reforms while undertaking the largest military operations in over a decade.

In August 2008, General Buyukanit will be succeeded as Chief of the TGS by General Ilker Basbug, the current commander of Turkey’s Land Forces Command. Basbug is on record as stating that the main purpose of the TSK and the state is the struggle against counter-revolutionary forces opposed to secular Kemalism (Yeni Safak, April 10, 2008).

The governing Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi – AKP) has gradually asserted greater civilian control of the military procurement process since 2002 as well as having undertaken steps to reduce the influence of the TSK General Staff in domestic politics in order to meet European Union standards on civil-military relations.

Though changes are underway, Turkey still maintains a vast conscript army of over one million men, the second largest in NATO and the largest in Europe. Despite having a much smaller economic base than many of its NATO partners, the large size of the Turkish military establishment has always found assured funding through the immense political presence the TSK wields in Turkish life. The military views itself as the guardian of the secular Kemalist republic and has repeatedly shown its willingness to intervene in Turkey’s politics as part of that role. At the moment, the TSK finds itself in the unusual position of fighting a cross-border counter-insurgency with the support of an Islamist government it has substantial differences with regarding the direction of the Turkish state. Despite critical words that were often harsh at times, the current leadership of the Turkish General Staff (TGS) has backed off in several recent confrontations with the government over issues that once would have seen TSK tanks rolling towards Ankara’s parliament building (these issues include the appointment of Islamist Abdullah Gul as the nation’s president and the volatile “head-scarf” debate). General Buyukanit expressed the concerns of the TGS when he recently warned of “reactionary circles” that were determined to pursue anti-secular activities in Turkey through various foundations and associations (Anatolia, April 4, 2008). Despite political support from the ruling Justice and Development Party for military reforms, the AKP’s plan to increase social spending throughout the country may initiate a rare debate on the future of Turkish military spending.

Turkey’s substantial defense industry consists of over 200 firms (many wholly or partly owned by the state) with an annual turnover of between $3 and $4 billion (Anatolia, February 26, 2008). There are over 1,000 Turkish sub-contractors with the number growing every day due to intensive state efforts to involve small and medium sized enterprises in the industry. Over 50,000 people are employed by the defense industry. Despite efforts to build a domestic arms-industry, Turkey remains the world’s fourth-largest importer of arms but the world’s 28th largest arms exporter. Turkey is aggressively seeking to increase its market share, expecting to increase its annual exports to $1.5 billion in the next three years (Anatolia, February 26, 2008). Turkey is also seeking to increase its share of domestically produced military equipment from the current 25% to 50% and its share of NATO projects from 4% to 20% by 2011 (Jane’s Defence Weekly, May 9, 2007; TDN, February 26, 2008). According to the chief of Turkey’s national military procurement agency, Turkey’s annual defense spending is 11.3 billion per year, ranking it fifth in Europe and twentieth in the world (Today’s Zaman, April 15, 2008).

Turkey’s Geo-Political Situation

Turkey is located at the strategic crossroads of Europe, Asia, the Caucasus and the Middle East. As such, it shares borders with no less than eight countries; Bulgaria, Greece, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, Iraq and Syria. Far larger than its land borders are Turkey’s 8,300 km of coastline along the Mediterranean, Aegean and Black Seas.

Despite being NATO allies, Turkey and Greece retain long-embedded suspicions of each other’s motives and intentions, fuelled by unresolved disputes over the status of Cyprus and smaller territories in the Aegean Sea. An example of these tensions can be found in a press article by Ali Kulebi of Ankara’s National Security Strategies Research Center; “It is absolutely clear that if Greece believes that it has reached our military power one day, it would certainly attack Turkey without any question” (Turkish Daily News, December 3, 2007). General Buyukanit paid a visit to Greece in 2006 at the invitation of Chief of the Hellenic National Defense General Staff Admiral Panagiotis Chinofitis, during which a number of initiatives were launched to increase greater cooperation between the two NATO allies (Turkish General Staff Press Release BA 29/06). The current Greek Chief of Staff, General Dimitrios Graspas, met with General Buyukanit in Ankara in late May of this year to discuss confidence building measures (Hurriyet, May 29; CNNTurk.com, May 26).

The increasing threat posed by the development of ballistic missile programs in neighboring countries (particularly that of Iran) has compelled Turkey to respond to this growing threat by the development of its own missile program. Turkey has also entered into talks with Iran over greater military cooperation, particularly against Kurdish rebels based in northeastern Iraq’s Qandil Mountains. The Kurdistan Workers Party (Partiya Karkere Kurdistan – PKK) has gradually become almost inseparable from the Iranian Kurdish Party for a Free Life in Kurdistan (Partiya Jiyana Azad a Kurdistane – PJAK), which carries out attacks on Iran from its bases on the Iraqi side of the border.

Turkey’s participation in international arms markets has frequently been hampered by issues such as human rights concerns over Turkey’s methods in combating PKK terrorists and even the lingering debate over the so-called “Armenian genocide” allegedly carried out by Ottoman forces during the First World War. Despite clear expressions of Turkish displeasure, the debate has been most strongly pursued in the legislatures of Turkey’s NATO partners in Western Europe and North America. Israel has also become involved of late and the whole issue has become a contributing factor in the selection of bids for arms sales or military-industrial partnerships with Turkey.

Military Challenges

Turkey has taken enormous strides in developing its military capabilities, currently fielding the second-largest military in NATO and the second most technologically advanced military in the Middle East. While Turkey is certainly prepared for conventional warfare, the question is whether the TSK’s size and structure prepare it to address the new threats posed by asymmetrical warfare.

Today Turkey is on the path of developing a smaller, more professional military force in much the same way its European and North American allies have already done. The usefulness of massive conscript armies is rapidly fading as new military technologies require highly-trained professionals to operate them. The cost of maintaining such a personnel-heavy military establishment is rapidly becoming prohibitive and the changing nature of security threats, from nation-states to small non-state forces such as guerrilla groups or terrorist cells, also requires greater specialization with a new emphasis on intelligence work. The U.S. commander in Iraq, General David Petraeus recently noted that sophisticated intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance equipment had become the key to battlefield success (Army Times, April 14, 2008). Where Ottoman armies in the field were once notorious for ignoring the most basic concepts of reconnaissance or intelligence collection (to their continual expense on campaign), today’s TSK is eager to embrace and integrate the most modern methods of intelligence collection in their strategic and tactical planning. General Buyukanit has stated that future military operations will be based on information management, requiring a core of highly trained and educated professionals; “The essential point will be to know everything about the adversaries, to minimize the information they have and to use their information to our advantage” (Jane’s Defence Weekly, October 4, 2006).

In modern asymmetric warfare, conventional militaries have to cope with scattered opponents fighting from multiple locations. A variety of unconventional methods, including terrorism, are typically used by the weaker party to undermine militaries based on the conventional 20th century model. Every means will be sought and used to exploit vulnerable points in the state with political significance and utility guiding the means and timing of strikes against the state or its security apparatus. Asymmetric threats may also be coupled with more conventional threats. To deal with these wide-ranging security challenges General Buyukanit has sought to create a professional force, “capable of performing conventional and asymmetric combat; a more modern TSK that can assume assignments given by the constitution and the laws with a smaller number of troops” (Anatolia, April 4, 2008). Continued rivalry in Turkey between the Interior Ministry and the TSK over responsibility for “homeland security” is a major stumbling block to developing strategies for meeting asymmetric challenges (Jane’s Defence Weekly, May 9, 2007).

The TGS has expanded the range of threats it must now guard against to include terrorism, sabotage, the deployment of weapons of massed destruction (WMDs) and organized crime (Jane’s Defence Weekly, October 4, 2006; May 9, 2007). New arms and other equipment will be needed to meet these challenges; in an October 2006 article, General Buyukanit provided a specific list of the TSK’s needs as it moves towards modernization:

- Tactical wheeled armored vehicles;

- Procurement of tanks as interim requirements;

- Attack and tactical reconnaissance helicopters;

- Utility helicopters;

- Unmanned aerial vehicles;

- Multiple launch rocket systems;

- 155 mm self-propelled and towed howitzers;

- Fire support automation;

- Air-defense early warning and control systems;

- Low- or medium-altitude air-defense systems, tactical area communications;

- A tactical command and control system; and

- A logistics management system. (Jane’s Defence Weekly, October 4, 2006).

Turkey has also assumed responsibilities in UN and NATO peacekeeping missions and counter-terrorism efforts. In October 2006, Turkey contributed 1,000 troops to the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), including military engineering and naval units. Today it maintains 752 troops in Kosovo Force (KFOR) and 750 troops in the Afghanistan International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), where Turkey’s refusal to commit these troops to combat theaters has caused a diplomatic rift with Washington.

Conventional Warfare, Traditional Allies

Turkey became a member of NATO on February 18, 1952, at which time it initiated a program to modernize its armed forces to better integrate with its new NATO allies. This process was aided by NATO assistance and military credits. During the PKK insurgency of the 1990s, several European states tried to apply restrictions to the use of weapons and military equipment purchased by Turkey.

Despite occasional impatience with its allies’ views on Turkish history and Turkey’s methods of dealing with its security concerns, there is every sign that Turkey has no intention of changing its approach to defensive alliances. According to General Buyukanit; “Victory in battles of today and the next 15-20 years’ time will not belong to a single force alone. Instead, we have seen in recent regional crises and the Gulf Wars that one country’s armed forces is not sufficient to resolve these conflicts. Therefore, we will continue to participate in operations with the forces established within the scope of both NATO and UN” (Jane’s Defence Weekly, October 4, 2006).

Still awaiting approval for membership in the European Union, Turkey’s defense establishment has run into problems with changes in the European Union’s defensive alignment that have been interpreted as being exclusionary with regards to Turkey. In an early April interview with an organ of the Turkish defense establishment, General Buyukanit described Turkey’s dissatisfaction with being excluded from full participation in the decision-making process of the European Security and Defense Policy (ESDP), the basis for a European Union defense alliance that has grown out of the earlier Western European Union (WEU); “Since the transfer of most of the WEU’s powers to the EU, some full members of the WEU have lost almost all of their rights… Turkey makes a substantial contribution to the EU’s efforts for European security, but it also supports the primacy of NATO in this respect. The inseparability of security obliges non-EU countries to be active in ESDP. No discrimination should be allowed” (Savunma ve Havacilik, April 2008; EDM, April 7, 2008).

ASYMMETRIC CHALLENGES IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Asymmetric Warfare and the PKK

Lieutenant General Servet Yoruk, commander of the TSK’s Special Forces, recently spoke on the development of asymmetric threats following the end of the Cold War. Defining asymmetric threats as “a means which is used by the weak to confront the strong or between even powers to defeat one another basing their actions on difference and superiority,” the General suggested that such threats are “mostly created by ethnic unrest, gaps between living conditions of different countries, undemocratic regimes, [the] spread of weapons of mass destruction, illegal immigration and other results of globalization.” The Special Forces have important tasks in reconnaissance, target identification and direct action to destroy terrorists and their infrastructure (Defence News, March 31, 2008).

Turkish raids on northern Iraq in February and March of 2008 demonstrated an ability to mount highly-integrated aerial attacks with helicopter-borne assault teams. With the availability of real-time intelligence from U.S. surveillance sources (and to a lesser degree, Israeli-built drones), Turkish planners have also demonstrated an ability to quickly interpret and exploit such information in deadly strikes on PKK targets.

The TGS has been gradually moving away from identifying military force as the sole solution to terrorist threats; according to General Buyukanit, “terrorism has economic, social and political dimensions as well as its security dimension. Terrorism can only be eliminated with a fight comprising all those dimensions” (Anatolia, April 4, 2008).

The Internal Terrorist Threat

In Turkey the threat of terrorism comes from a variety of players; the domestic right and left wing, ethnic-nationalist groups, and both domestic and foreign-based religious extremists. Terrorism occurs in both rural and urban areas and strikes both civilian and military targets. Militant groups active within Turkey include the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), al-Qaeda, the Turkish Hizbullah, and the Great Eastern Islamic Raiders’ Front (IBDA-C). Meeting this security challenge has required the efforts of the military, the gendarmerie, various intelligence groups and Turkish police across the country.

A homeland security plan intended to coordinate Turkey’s defense industries and security structures under the auspices of the Ministry of the Interior in cooperation with the Undersecretariat for Defense Industries was developed in 2001 but never implemented due to inter-organizational rivalries (Today’s Zaman, March 25, 2008).

Military Reforms

The “Kuvvet 2014” (Force 2014) reform program calls for a 20% to 30% reduction in the size of the Turkish Land Forces Command (TLFC). According to General Buyukanit; “The main purpose of the TLFC in the future will be to reach a force structure that will enable us to respond to conventional and asymmetrical risks and threats; to conduct operations day and night in any environment and situation; to take decisions more swiftly than any adversaries; and to have available weapons with longer ranges than those of our adversary” (Jane’s Defence Weekly, May 9, 2007).

Buyukanit has described the Turkish Land Force of the future: “Force-2014 aims for a TLF that is smaller; trained for each mission; capable of fighting in high and low intensity conflicts; rapidly deployable, sustainable and survivable; and capable of conducting joint and combined operations. The force will possess adequate firepower; sufficient air-defense systems; and effective command and control systems” (Jane’s Defence Weekly, October 4, 2006; Savunma ve Havacilik Dergisi, August 2006). The new TLF will be based on rapid-reaction forces with local and strong, centrally located strategic reserves (Jane’s Defence Weekly, October 4, 2006).

Important changes have already been made to the way Turkey tackles PKK insurgents on the ground. The detachments of roughly 15 conscripts led by an NCO that once were the mainstay of the Turkish war against the PKK are being phased out, replaced by all-volunteer units of highly-trained Special Forces personnel. In June 2007, Land Forces Commander General Ilker Basbug announced a plan calling for the creation of six Special Forces brigades composed entirely of professional soldiers of the rank of sergeant and above (Today’s Zaman, June 28, 2007; October 22, 2007). These reformed commando brigades are expected to be fully operational by the end of 2009. The move to a professional counter-terrorist force is expected to increase operational efficiency while tempering public anger over the losses of poorly-trained conscripts to ambush or improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

TURKEY’S ARMS INFRASTRUCTURE

The Undersecretariat for Defense Industries (Savunma Sanayii Mustesarligi – SSM)

The Ministry of National Defense Undersecretariat for Defense Industries (Savunma Sanayii Mustesarligi – SSM), Turkey’s military procurement agency, is designed to coordinate the activities of Turkish defense industries with Turkish military requirements, as well as encourage the development of new enterprises and technology. Through the SSM the state is also able to facilitate the work of the defense industries through seeking foreign capital investments and the development of a modern, integrated defense industry infrastructure. The SSM defines its mission as the “modernization of the Turkish Armed Forces and the improvement of the defense industry.” The goals of the SSM include the development of technological expertise, the creation of an export infrastructure and the strengthening of side sectors or related industries. The SSM also oversees the issuance of contracts for arms/equipment purchases from foreign suppliers. Murad Bayar was a consensus choice between the AKP and the TGS to head SSM in 2004.

The SSM was established in 1985 under the Defense Industry Law and exists as a legal entity in its own right with its own extra-budgetary resources. Its main purpose is to facilitate the modernization and expansion of the Turkish defense industry and implement the decisions of the Defense Industry Executive Committee (Savunma Sanayii Icra Komitesi –SSIK), the main decision-making group, consisting of the chief of the SSSM, the Prime Minister, the Defense Minister and the Chief of the General Staff. As an arm of the government, the SSM has a hand in creating favorable resolutions to trade issues and the provision of necessary financial and economic support to the defense industry. The SSM has its own source of capital independent of national defense budget appropriations, with direct access to a percentage of taxes levied on fuel, income, corporate, tobacco and alcohol. These funds are handled by a division of the SSM, the Defense Industry Support Fund.

The SSM is currently working within the outlines of a five-year (2007-2011) strategic plan. The plan calls for the SSM “to conduct supply activities effectively in accordance with the expectations of the users, to improve international cooperation in the field of defense industry and to establish an effective institutionalized structure to realize [the] abovementioned activities…” (Murad Bayar in Defence Turkey Magazine 2(10), 2008).

Most deals negotiated with foreign partners by the SSM usually call for some reciprocal purchase of goods from Turkey, either part of the defense production the partner is engaged in (offsets), or some other type of Turkish-produced goods.

Turkish Armed Forces Foundation (Turk Silahli Kuvvetlerini Guclendirme Vafki – TSKGV)

A military-run charitable trust with financing outside the national budget, the TSKGV is a major economic force in the development of the Turkish arms industry. The foundation is obligated to spend 80% of its annual gross income – of this 65% goes towards TSK projects and the remaining 35% towards defense industry investments. The foundation typically purchases defense systems required by the TSK from Turkish manufacturers.

According to the TSKGV’s general manager, retired Lt. General Engin Alan; “The foundation’s direct contribution to the defense industry is carried out by establishing new companies, being a partner of the present companies, increasing its shares in companies and participating in raising its companies’ capital. The funding required for these activities is met through 35% of the foundation’s income allocated for the defense industry” (defenseturkey.com). The TSKGV is also responsible for hosting international defense industry fairs.

Weapons of Mass Destruction: A Road Not Taken

There is no evidence that Turkey is pursuing nuclear, chemical or biological weapons, though the PKK has alleged that the TSK used chemical weapons against its fighters and Kurdish peasants in 1988 and again in 2006 (Human Rights Watch: Iraqi Kurdistan – The Destruction of Koreme During the Anfal Campaign, 1992; Firat News Agency, February 26, 2006; February 28, 2006). Turkey’s position on WMD is given on the website of the Turkish General Staff; “Turkey does not possess WMD and does not intend to have them in the future. Turkey adheres to all major international treaties, arrangements and regimes regarding non-proliferation of those weapons and their delivery means, and actively participates and supports all efforts pertaining to non-proliferation in the NATO” (tsk.mil.tr).

Concerns have been raised in some quarters that Turkey’s pursuit of nuclear power may create favorable conditions for the construction of nuclear weapons, but Turkey’s nuclear projects are under the supervision of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA); for the moment the only nuclear devices in Turkey are in the hands of the U.S. Air Force at Incirlik Air Base. Turkey supports Iran’s efforts to build civilian-use nuclear power plants, but opposes attempts by Iran or any other Middle Eastern nation to introduce new nuclear weapons into the region. Turkish Foreign Minister Ali Babacan has stated Turkey’s opposition to U.S. diplomatic efforts to isolate the Islamic Republic; “Simply isolating Iran in our view caused Iran to be more united, to weaken the hands of the reformists… Also [it led to an] Iran which had more and more influence in the region” (Today’s Zaman, April 4, 2008).

The Road to Self-Sufficiency

The biggest challenge to building a functioning domestic arms industry was Turkey’s small technological base. For a time this hampered Turkey’s international competitiveness. To deal with this problem, the TSK has defined 11 “Technology Activity Fields” and 109 “Technology Areas” in which to focus development according to immediate and long-term requirements (Turkish Daily News, December 3, 2007). Competitiveness remains a major problem in the Turkish arms industry, with the TSK frequently finding it cheaper to buy foreign products than rely on domestic development (EDM, December 6, 2007).

International cooperation on arms projects is seen as a means of closing the technology gap; “The technological level of the defense industry and international cooperation opportunities feed each other and have a triggering relationship. As its technological infrastructure improves, our industry strengthens its position as a suitable candidate for new partnerships, and as it attends to new international projects, it gets opportunity to improve its capabilities” (Murad Bayar; Defence Turkey Magazine 2(10), 2008). Turkey also pursues an aggressive policy on offset sales designed to promote exports and self-sufficiency as well as reduce the national balance of payments (Today’s Zaman, May 21, 2007).

TURKEY’S MAJOR ARMS INDUSTRIES

Aselsan is the largest defense company in Turkey, specializing in military electronics and communications systems. The state-owned manufacturer produces many systems under U.S. license, including battlefield communications equipment as well as components for several other major Turkish defense projects. It has become a major exporter of military equipment.

Aselsan was founded by the Turkish Armed Forces Foundation in 1975 to produce military radios and electronics for the TSK. Today it consists of three divisions; the Guidance and Electro-Optics Division, the Communications Division and the Microwave and System Technologies Division.

Among Aselsan’s many products is the Turkish produced Aselsan Pedestal Mounted Air Defense System (PMADS), a self-propelled surface-to-air missile system that comes in two mobile land versions, ATILGAN and ZIPKIN (Jane’s Land-Based Air Defense, March 26, 2008), as well as a naval version, BORA The systems carry four to eight Stinger missiles. Aselsan’s frequency-hopping/software-based radios have been sold to Egypt and Pakistan. Among its most important projects is its work as a subcontractor with the Israel UAV Partnership (IUP) and Elbit Systems in the development of Heron unmanned aerial vehicles (Defense Industry Daily, September 13, 2005).

Aselsan is currently working on a major surveillance and detection system to defend the Turkish Aksaz and Foca naval bases with Kongsberg of Norway as a subcontractor.

Owned by the Turkish Armed Forces Foundation, this software manufacturer achieved Turkey’s first high-tech export in 2006 by selling CN-235 flight simulators to South Korea. Havelsan is also involved in naval technology projects, such as the National Ship Project (MILGEM) and the GENESIS project (Gemi ENtegrE Savab Ydare Sistemi), designed to upgrade the combat management systems of the Turkish Navy. GENESIS involves a high degree of automation in the combat management systems and will also reduce reaction time for missile defense systems.

Havelsan aims to become one of Europe’s leading IT companies through the indigenous development of software-intensive defense systems, using regional and global partnerships to boost its international competitiveness (Havelsan GM Faruk Yarman; Defence Turkey Magazine 2(10), 2008). One of Havelsan’s biggest projects has been the manufacture and export of CN-235 flight simulators to South Korea.

Havelsan is deeply involved in improving Turkey’s electronic surveillance, reconnaissance and intelligence capabilities. To this end Havelsan plays a large role in the Early Warning and Command Control System Project (Peace Eagle), and acts as a subcontractor to France’s Thales Airborne Systems in the Maritime Patrol Aircraft project (MELTEM), which involves a significant degree of technology transfer. MELTEM involves the installation of Thales’ Airborne Maritime Situation Control System (AMASCOS) into modified CN-235 aircraft belonging to the Turkish Navy and Coast Guard (Thales Press Release, September 12, 2002). Another major project is the Airforce Information System, an integrated battle management system. Havelsan is a sub-contractor to Lockheed-Martin on the Joint Strike Fighter project (see below). Various administrative software programs are also produced by Havelsan for use by the TSK and the national government.

- Makina ve Kimya Endüstrisi Kurumu (MKEK)

State-owned MKEK (Machine and Chemical Industries Corporation) was founded in 1950 as the successor company to the General Directorate of Military Factories, established with the end of the War of Liberation in 1923. MKEK is Turkey’s largest arms manufacturer and is owned by the Ministry of Industry and Trade. It operates a dozen factories in Turkey (Ankara, Cankiri and Kirikkale), with a limited amount of mostly dual-use civilian production. Its main products are small arms (particularly G-3 rifles and MG-3 machine guns), machine guns, antiaircraft weapons, multiple launch rocket systems, antitank weapons grenades and ammunition (mkek.gov.tr). Over 80% of Turkey’s small arms and ammunition needs are met by MKEK. The G-3 A3 and G-3 A4 rifles are variations of the standard NATO 7.62mm rifle made under license (as are most MKEK products). Another notable product is the HK-33 (Heckler and Koch) 5.56mm assault rifle.

Turkey’s replacement for the G3 will be the Mehmetcik I assault rifle (similar in design to the HK-416 according to some observers). The rifle will be made in Turkey without having to pay license fees; production of the G3 will undoubtedly be a cornerstone of Turkey’s efforts to become a major player in the international arms markets.

MKEK has been directed by SSM to begin producing 40 mm grenade launchers from its plant in Cankiri. According to the Turkish press, “Plans have been made to use the automatic grenade launchers in the struggle against terror” (Hurriyet, April 14).

Otokar is a sub-division of privately-owned Koc Holding, Turkey’s largest industrial conglomerate, and is a major Turkish manufacturer of civilian vehicles (mainly buses and mini-buses) and makes the multipurpose Cobra armored vehicle, 4X4 armored personnel carriers and a variety of other armored vehicles for military and internal security use.

- Roket Sanayii ve Ticaret A.S (Roketsan)

Roketsan is Turkey’s chief producer of rockets and missiles. The company has been heavily involved in several major consortium projects, including European production of Stinger surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). Roketsan also makes the 122mm Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) and the 300mm T-300 Multi-Barrel Rocket Launcher (MBRL).

- Turk Havacılık ve Uzay Sanayii A.S. / Turkish Aerospace Industries, Inc. (Turkish acronym: TUSAS; English acronym: TAI)

Parent Company TUSAS Aerospace Industries (TUSAS) merged into a single corporate identity in 2005 with Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI), Turkey’s second-largest defense company (TDN, March 16, 2005). There were initial fears that the merger would harm competition, as the SSM might feel obliged to sole-source work to the new arms giant. Since April 5, 2007, the company has been known as TUSAS in Turkish and TAI in English.

TAI bought out Lockheed-Martin’s 42% share and General Electronics International’s 7% share in the company in January 2006 as part of an effort by SSM and TSKGV to consolidate the Turkish defense industry. Murad Bayar suggested as much as 80% of the company could eventually be privatized (Jane’s Defence Weekly, January 25, 2006).

TAI maintains a factory on the Murted Air Base near Ankara, where it was involved in a joint project through the late 1980s to the late 1990s with General Dynamics and General Electric to build 240 F-16 C/C aircraft (with TUSAS holding a 51% interest in the project). A number of these planes were sold abroad to other Middle Eastern countries.

TAI partnered with Construcciones Aeronauticas, S.A. (CASA) of Spain to build 52 CN-235 medium-range, twin turbo-prop transport/maritime patrol aircraft for Turkish use. TAI also manufactures parts for Eurocopter Cougar AS-5322 search and rescue helicopters and Aermacchi SF-260-D trainers (Anatolia, February 26, 2008). TAI is involved in the modernization of 69 Northrop T38-A supersonic jet trainers and acts as a supplier for AgustaWestland, Airbus, Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, MDHI and Sikorsky.

Most of the development of Turkey’s unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) is being done by TAI.

ARMS PROJECTS BY TYPE

Armor

Turkey’s main battle tanks are the German-built Krauss Maffei Wegmann Leopard 2A4 (built between 1985 and 1992) and the M60T, a highly upgraded version of the M60 Patton, using Israeli weapons and technology transferred to Turkish manufacturers (in Israel this version of the M60 is known as the Sabra Mk. III). After some delays, work is about to begin on an Israeli-Turkish jointly produced upgrade of 170 U.S. built M60-A1 Turkish tanks in Kayseri. The $688 million project through main contractor Israel Military Industries will use advanced systems from Israel’s Merkava main battle tank with a significant degree of technology transfer (Hurriyet, March 25, 2008). Turkish MKEK and Aselsan are both involved in the modernization project. The deal for the German Leopards involved extensive training and technology transfers as political criticism in Germany of possible Turkish use of the tanks against the Kurds diminished from previous levels (UPI, November 11, 2005).

A major upgrade of 166 Turkish Leopard 1A1/A1A4 tanks by Aselsan is nearing completion. The main focus of the upgrade was to improve the tanks’ firing systems through installation of the Turkish-produced VOLKAN fire control systems, which will allow for increased capability target acquisition in all light and weather conditions.

Turkey has committed to a major undertaking to become one of the few countries in the world to produce a main battle tank. The project’s main contractor is OTOKAR, with Aselsan, Roketsan and MKEK as sub-contractors. Four prototypes are scheduled to be delivered by 2012, with the eventual manufacture of 250 Turkish-made main battle tanks with input from South Korean or German sub-contractors.

Aviation

Turkey has made several upgrades to its fleet of warplanes to better deal with the asymmetric threat. These upgrades are mostly designed to increase the air force’s capacity to operate at night and attack ground targets with precision in any kind of weather. Over 200 F-16 C/D aircraft have been fitted with Lockheed-Martin’s LANTIRN (Low Altitude Navigation and Targeting Infrared for Night), which consists of an externally mounted navigation pod and a targeting pod. Used in tandem, this equipment allows low-flying aircraft to strike with precision despite adverse conditions. Turkey has the second largest fleet of F-16s in the world after the United States. Over 100 older F-4E and F-5A/B fighters have been similarly upgraded by Israeli contractors. Laser, infrared and TV-guided munitions are available for all these aircraft (World Politics Review, November 7, 2007).

In 2007 U.S. firm Lockheed Martin supplied 30 F-16 Block 50 fighters under a deal signed in 2006(DefenseNews.com, July 16, 2007). It was first proposed to mount electronic warfare systems locally made by Aselsan into the fighters, but the Air Force Command eventually settled on U.S. made ITT systems (Milliyet, February 2, 2008).

Turkey is also a participant in the multinational Joint Strike Fighter (JSF-35) project in a consortium including the United States, Great Britain, Canada, Norway, Denmark, Australia, Italy and the Netherlands. Turkey expects to deploy its first JSF-35 fighters in 2014. A number of Turkey’s 215 F-4 and F-16 fighters are expected to reach the end of their operational life beginning in 2010 (Anatolia, March 27, 2008). The rest will need to be decommissioned by 2020. Turkey plans to buy 100 of the F-35 fighters for an estimated $11 billion. The JSF project won over intense bidding from the manufacturers of the twin-engine Eurofighter Typhoon, produced by a British/German/Italian/Spanish consortium, Eurofighter GmbH. The consortium is leaving an option open for Turkey to join as a production partner before 2012. The selection revealed Turkey’s “asymmetric warfare” priorities – the JSF is viewed as the better option for air-to-ground attacks, while the Eurofighter is viewed as superior for air-to-air action (Turkish Daily News, May 29, 2006).

The F-16s are most useful in the counterinsurgency against the PKK when they are given precise targets beforehand. They are less useful for reconnaissance in mountainous country, a job better suited for Turkey’s Cobra helicopters. Turkey’s goal of dramatically increasing its battlefield intelligence collection capabilities will be greatly furthered when it takes delivery of four Boeing 737 Airborne Early Warning and Control aircraft (AEW&C), but delivery has been delayed for nearly two years due to problems with the software and radar. Installation of the Northrup Grumman Multi-role Electronically Scanned Array radar system is being done by Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI).

Helicopters

Turkey makes extensive use of its small fleet of attack helicopters and larger fleet of transport/utility helicopters to create a massive advantage in mobility and firepower in its struggle against the PKK. The helicopter has emerged as one of the most important tools in addressing asymmetrical military challenges. All Turkey’s attack helicopters are equipped for flying low-altitude missions using night-targeting systems.

Turkey’s search for new co-produced attack helicopters began in 1995. American firm Bell Helicopter Textron was chosen to supply 145 AH-1Z Super Cobra (or Viper) helicopters in 2000 over competition from U.S. Boeing, Italian Agusta, Franco-German Eurocopter and the Russian-Israeli Kamov-IAI. It is believed that Turkey kept Kamov in the competition long after the decision had already been made in order to put pressure on the U.S. to allow technology transfer and grant an export license, the latter being at risk at the time over human rights issues related to the conduct of Turkey’s war against Kurdish separatists. The deal eventually fell apart in 2002 due to technology transfer issues. Negotiations then opened with the Russian-Israeli partnership Kamov-IAI but this deal too collapsed by late 2003. SSM requirements that the helicopters include Turkish produced mission computers drives many potential partners away (TDN, November 23, 2005).

In September 2007, the SSM and Agusta Westland signed a deal for the production of 51 (+41 optional) A-129 Mangusta (Mongoose) attack and reconnaissance helicopters by Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI) and Aselsan in Ankara. TAI is the main contractor. The engines are to be made by Tusas Engines Industries in Turkey (Today’s Zaman, March 31, 2008). This was not the end of Turkey’s long search for attack helicopters, however, as the deal with Agusta was thrown into jeopardy in late March when the U.S. refused Agusta’s request for the transfer of technology used in the helicopters’ T800 engines. There is also dissatisfaction reported in the TGS over the suitability of the A-129 – the helicopter has never been exported before and has only seen service with the Italian armed forces. The military is said to prefer bids by Eurocopter and Boeing (Defense Industry Daily, September 17, 2007). Under the agreement with Agusta Westland, Turkey may market the helicopters anywhere in the world except Italy and Great Britain, allowing Turkey to become an exporter of helicopters for the first time.

A greater emphasis on Special Forces operations in the TSK will require more military transport helicopters. At present a fleet of 90 Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters is available to transport infantry and Special Forces units. Each Black Hawk can carry sixteen men. On April 17, Turkish Defense Minister Vecdi Gonul announced that Turkey would purchase 84 general purpose Sikorsky S-70 Blackhawk helicopters (the export model of the UH-60) from the United States in a deal worth $2.5 billion, though not all the helicopters are for military use (Anatolia, April 17, 2008; Defense News, April 14, 2008). The deal follows a 2006 purchase of 17 Sikorsky S-70B Seahawk export-model maritime helicopters (U.S. designation H-60) off-the-shelf in a $580 million deal (DefenseNews, July 16, 2007).

Turkey’s 32 single-engine AH-1 Cobra and nine twin-engine AH-1W Super-Cobra attack helicopters have seen extensive service in the campaign against PKK militants in southeastern Turkey and northern Iraq. The helicopters are made by Bell Helicopter Textron. Efforts to obtain ten additional used Cobra helicopters from the United States have failed, due officially to American needs in Afghanistan and Iraq, but the appropriateness of the request after U.S. firms had effectively been disqualified from competing in the attack helicopter competition may have played a role (DefenseNews.com, January 28, 2008; Today’s Zaman, April 13, 2008). Turkey’s existing Super-Cobras have been heavily upgraded and are fully capable of night operations.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

Turkey possesses a number of types of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), which it has used to great advantage in the difficult terrain of southeast Turkey and northern Iraq. UAV data is analyzed at Batman Air Force base while operational orders based on this intelligence are made at 2nd Army headquarters at Malatya (Hurriyet, March 25, 2008).

Turkish drones include the following types:

- GNAT-750 – Produced by General Atomic, this surveillance system has a 48 hour flight time and can carry a 150 kg payload. Turkey purchased eight of these in the 1990s but only one or two remain operational (Turkish Daily News, December 27, 2007).

- Harpy –Turkey bought roughly 100 of these from Israel Aircraft Industries in 1999. With a 500 km range, the Harpy is designed to detect, attack and destroy enemy radar installations.

- Heron – The Israeli-made Heron TP (known as the “Eitan” by the Israeli Air Force) is described as a “medium-altitude, long-endurance UAV,” capable of carrying out a variety of operational missions while staying in the air for several days at a time. The aircraft is 46 feet long, weighs five tons and can carry an additional half-ton of sensors in its forward section. A single Canadian-made 1,200 horsepower Pratt & Whitney turbo-prop engine allows the craft to fly at altitudes over 40,000 feet with a 1,000 km range and 250 kg payload.

There is strong dissatisfaction within the TSK with the failure of state-run Israeli Aerospace Industries (IAI) and Elbit Systems to meet the delivery deadline of October 2007 for the Heron UAVs, with delivery now pushed back to spring 2008. A malfunctioning camera system produced by a Turkish subcontractor has been blamed for the delay (CP, December 27, 2007). To mollify the TSK, the Israelis offered to lease IAI Heron UAVs together with Israeli operating crews for a twelve-month period at a cost of $10 million (Haaretz, December 27, 2007). The work of the Israeli crews in gathering intelligence on the PKK was recognized publicly by Defense Minister Gonul (CNN Turk, February 12, 2008).

The Israeli firms beat out U.S. (General Atomic Predator) and French competition to supply 20-30 UAVs in a contract worth nearly $200 million. Turkey is expected to finally take delivery of ten Israeli Herons in mid-2008.

Based on its favorable experience with UAVs, Turkey is determined to master the necessary technology and bring its own models online. Turkish-made drones were first deployed operationally in late January, 2008 (Anatolia, January 28, 2008). UAV types under development include:

- TIHA – Turkey is working on its own version of the Heron, the Turkish Indigenous Medium Altitude Long Endurance UAV. Prototypes are in development and it is hoped that the first flight will take place in 2009. TIHA is projected to fly for 24 hours at a maximum height of 30,000 feet in a variety of weather conditions.

- Gozcu – The Gozcu close range tactical UAV is designed and manufactured by TAI. With a maximum altitude of 10,000 feet, this surveillance platform can transmit live video feeds over 50km. TAI is likely to begin mass-production of the Gozcu after successful trials.

- Turna: TAI launched a successful test flight of its “Turna” target drone in April 2008. The Turna is made entirely in Turkey, with a turbo-prop engine built by TEI (TAI Press Bulletin, April 4, 2008).

Missiles

Having declined participation in the proposed U.S. anti-ballistic missile shield, Turkey is currently seeking to fill a $1.4 billion contract for four long-range missile and air defense systems, though there are reports that Turkey is now seeking anywhere from four to twelve additional systems (Sabah, April 30; Today’s Zaman, March 19, 2008). Russia is offering the S-400 Triumf air defense system (NATO designation: SA-21 Growler), which has already interested Iran and China, among others. The S-400 system is built by Russia’s Almaz Central Design Bureau and is a substantially upgraded version of the S-300 system, which Russia had offered initially. Russian sources claim the system is capable of destroying stealth aircraft, cruise missiles and ballistic missiles (RIA Novosti, April 30, 2008; see also Eurasia Daily Monitor, May 7, 2008).

Long-term Russian support and maintenance for the system is a major concern for Turkey (Today’s Zaman, October 3, 2007). A previous purchase of Russian-made BTR infantry fighting vehicles and M-17 helicopters ended badly when Russia failed to provide spare parts or maintenance assistance for these products, eventually rendering them useless to the TSK.

U.S. companies Lockheed-Martin and Raytheon are also competing for the missile contract, offering Patriot Advanced Capability (PAC) 2 and PAC 3 upgraded missiles through Foreign Military Sales credits. U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates has warned Turkey of interoperability problems with NATO systems if Turkey goes with the Russian bid (Today’s Zaman, April 14, 2008). Despite this, Russia may still be able to seal the deal if it offers significant technology transfer as part of its package. China has offered its HQ-9 medium to long range missile system partly based on the Russian S-300 system and, allegedly, the U.S. Patriot system. The SSM is now looking into the procurement of low-altitude air defense systems (Today’s Zaman, April 10, 2008).

Naval Forces

Naval Forces

With Turkey’s extensive coastlines and dependence on maritime shipping Turkey’s navy (Turk Deniz Kuvvetleri – TDK), plays a vital role in guaranteeing the security and economic safety of the nation. According to SSM director Murad Baytal; “After the embargo in 1974, we adopted the idea that ‘we can build our ships in our own shipyards’ and took extra investment on shipbuilding” (Defence Turkey Magazine 2(10), 2008).

Turkey is working towards becoming an independent builder of larger naval vessels through MILGEM (Milli Gemi), the National Ship Project, launched in 2005 at the naval shipyards in Istanbul. MILGEM is intended to provide the Turkish navy with twelve modern corvettes equipped with Mk.41 vertical launching systems and indigenously produced GENESIS combat management systems. The first product of this program, TCG Heybeliada, is scheduled for launch in September 2008, with commissioning in 2011. Work on a second ship has been started. Havelsan and Aselsan are both involved in the supply and integration of naval warfare systems on this project.

Istanbul’s Yonca Onuk shipyard (which normally specializes in fast patrol craft) is building two to four new submarines for completion in 2014 under the New Type Submarine Project. Turkey hopes to build most of the ships with a foreign contractor as the technology supplier in a project that might be worth $2.5 to 3 billion. German, French and Spanish firms have put in bids for the contract (Defense News, April 14, 2008). An Aselsan-Havelsan partnership has been given the task of renewing the equipment and systems of Turkey’s diesel-electric Atilay class submarines (Today’s Zaman, April 10, 2008). Yonca Onuk is also involved in the Fast Intervention Patrol Boat project. The construction of eight new corvettes is currently underway and work has begun on a $535 million contract with Istanbul’s Dearsan shipyards for the local construction of sixteen modern patrol boats. Yonca Onuk has successfully marketed its speed patrol boats to Malaysia, Georgia and Pakistan.

Prior to recent initiatives to develop Turkish shipbuilding capacity, much of the activity in this sector was carried out in cooperative projects with German firms. The main naval shipyard at Golcuk built frigates and submarines in the 1990s, while smaller shipyards produced a wide variety of naval craft, including fast-attack boats, destroyers, auxiliary ships and a host of small vessels.

On December 5, 2007, Defense Minister Vecdi Gonul announced that Turkish shipyards would undertake the construction of four new frigates at a cost of $1.6 billion (EDM, December 6, 2007). If successful, the TF-2000 project will end Turkey’s reliance on second-hand frigates from the United States, many of which were supplied on favorable terms in order to shift the Turkish market for naval technology away from Germany (Turkish Daily News, October 25, 2007). The frigate project will rely heavily on lessons learned in the MILGEM corvette project.

One of the main aims of April 2008’s Turkish- led naval exercise by the Black Sea Naval Cooperation Task Force (BlackSeaFor, involving ships from Turkey, Russia, Ukraine, Bulgaria and Romania) was training in “joint action to rebuff asymmetrical threats” (Agentstvo Voyennykh Novostey, April 10, 2008).

THE ARMS INDUSTRY AND FOREIGN POLICY

A Strained Relationship: The United States

The United State’s role as Turkey’s dominant arms supplier began with the application of the Truman Doctrine in 1947, which mandated the sales of large quantities of arms to Turkey and Greece to prevent them from falling under Soviet rule. The United States has dominated Turkish arms supply ever since, but Turkey is beginning to show a new willingness to seek military equipment elsewhere. U.S. sales to Turkey usually take the form of government-to-government sales through the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program administered by the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), or through commercial sales through tenders or sole-source purchases.

A limited embargo on U.S. arms sales to Turkey in 1975 following the Turkish invasion of Cyprus was a major factor in spurring Turkish efforts to develop self-sufficiency in arms production. Being cut off from its NATO ally compelled Turkish planners to look at previously untapped sources of military hardware and technology. A military electronics industry was formed to begin domestic production of military technology.

In 1995 and again in 1997 the U.S. State Department produced reports documenting the use of U.S.- supplied weapons in human rights abuses against Kurdish civilians in southeastern Turkey. (U.S. Department of State, 95/06/01 Report on Human Rights in Turkey and Situation in Cyprus; U.S. Department of State, U.S. Military Equipment and Human Rights Violations, Report to the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, July 1, 1997). The fallout from these reports had a negative effect on the sales of U.S. attack helicopters to Turkey. U.S. grants and loans for Turkish arms purchases from American manufacturers were cut off in 1998 when it was determined Turkey’s finances were strong enough to manage without such assistance (similar aid to Greece was suspended at the same time).

Turkey’s emphasis on technology transfers has run up against U.S. restrictions on military technology transfers, creating a significant impediment to continued U.S. arms sales to Turkey. US officials have expressed dislike for the SSM’s 2005 rules of acquisition, accusing the SSM of hindering NATO interoperability. The U.S. deputy assistant secretary of defense for Europe and NATO told a House of Representatives panel in March 2007 that the SSM was “hindering Turkey’s military modernization, interoperability with NATO allies and U.S.-Turkey defense industry cooperation… Onerous terms and conditions — liability, work share, technology transfer and upfront U.S. government approval requirements in Turkey’s standard contracts have kept U.S. firms from bidding” (DefenseNews, July 16, 2007). These restrictions played a major part in the inability of US firms to obtain a number of helicopter contracts from the SSM. Though the SSM has acted to ease Turkish conditions regarding such transfers in order to allow U.S. firms to re-enter the bidding process on Turkish arms tenders, existing Turkish demands for companies to obtain advance government authorization for export licenses have run afoul of U.S. law, creating continuing problems for U.S. manufacturers seeking to bid on Turkish arms projects (Jane’s Defence Weekly, May 9, 2007).

One benefit to the United States of arms sales to Turkey is enhanced interoperability of weapons systems with a NATO ally. This was one of the reasons cited by the Pentagon’s Defense Security Cooperation Agency (responsible for approving foreign arms sales) in its recent approval of a $227 million sale of six ship-based MK-41 vertical launch systems and two MK 41 VLS upgrade kits by Lockheed Martin Corporation (Reuters, April 9, 2008).

A new phase in Turkish-U.S. military cooperation began in November 2007, when the White House agreed to begin supplying real-time intelligence on northern Iraq to the TSK (EDM, November 6, 2007). Turkey remains one of the world’s leading markets for U.S. arms, but much of the Turkish arms development project appears designed to wean Turkey from reliance on U.S. supplies.

A New Defense Partner: Israel

The 1996 Turkish-Israeli deal on defense industry cooperation was intended to improve Turkey’s own domestic defense industry. There were initial hopes that the deal would allow for the transfer of U.S. military technology normally available only to Israel but this did not materialize despite Israel receiving a number of large contracts for upgrading Turkish tanks and warplanes. The impetus for military cooperation came from the TSK, while the Turkish government displayed greater reluctance to embrace Israel as an ally, denying the expectations of some observers who predicted the defense pact would draw the two nations into a strategic relationship (EDM, December 6, 2007; February 13, 2008).

In 2003 an $8 million contract with Israeli Aircraft Industries (IAI) to upgrade Turkey’s C-130 Hercules transports was cancelled due to IAI’s failure to meet the terms of the contract. A visit from Israel’s defense minister followed to assure Ankara that this would not happen again (Journal of Electronic Defense, July 1, 2003).

There is a growing dissatisfaction with the defense industry relationship with Israel, with complaints over substandard work, Israeli reluctance in technology transfers and delays in important projects, such as the much-needed Heron UAV project (EDM, December 6, 2007). There has also been substantial criticism of Turkish-Israeli defense cooperation from Turkey’s Islamist press; recently a columnist for Yeni Safak asked, “How much longer are we supposed to bear the shame of maintaining cooperation with Israel in [the] defense industry?” (Yeni Safak, January 23, 2008). Turkey is one of only four countries in the Islamic world to recognize Israel but there are substantial concerns in the AKP government with regard to Israel’s Palestinian policies. There are also concerns with the activities of Israeli security advisors and businesses supplying training and military equipment to Kurdish northern Iraq (Haaretz, December 27, 2007).

At a delicate time in Israeli-Turkish relations, the Israeli Knesset has scheduled a discussion on the “Armenian genocide” issue, despite a request by a Turkish parliamentary delegation to cancel the discussion. The Chairman of the Turkish Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, Hasan Murat Mercan, stated “I am convinced that Israel recognizes the negative implications this may have on ties between the two countries” (Haaretz, April 11, 2008).

Despite these tensions, Turkey continues to play an important role as an intermediary in peace discussions between Israel and Syria, though Turkey’s parliamentary opposition has raised concerns over the possibility of Turkish water sales to Israel (Hurriyet, May 28).

The Russian Alternative

As a NATO member, Turkey did not purchase arms from the Soviet Union, Russia’s predecessor state. During the embargo on U.S. arms in the mid-1990s, Turkey turned to Russia for tanks and military helicopters, but the relationship quickly turned sour when it turned out the agreement did not call for continuing logistical support and the Russian arms firms refused to provide the same. A deal was finally struck with a Rosoboronexport subsidiary to provide support, but this too failed when the company became embroiled in corruption charges in Russia and could not fulfill the contract (Today’s Zaman, April 15, 2008).

In April 2008, Russia’s state-managed Rosoboronexport won out over Israel’s Rafael Advanced Defense Systems and U.S. Raytheon for the Turkish contract for 800 medium-range antitank missile systems and 800 missiles (Kommersant, April 10, 2008; Agentstvo Voyennykh Novostey, April 14, 2008). The $80 to $100 million purchase of the Metis M-1 systems followed the success of Lebanon’s Hizbullah in using Russian-made antitank missiles against Israeli troops and armor in the summer war of 2006 (see Terrorism Focus, August 15, 2006). Though the systems will be purchased ready-made, there will still be substantial technology transfer in the deal (Interfax, May 2, 2008).

In the last few years Russia has joined Turkey in several military exercises focused on combating asymmetrical threats in the Black Sea region. These joint initiatives follow centuries of Russian-Turkish struggles for control of the Black Sea.

The Eastern Alternative: Korea

South Korea, through its state-managed Korea Aerospace Industries (KAI), is seeking to build a long-term defense partnership with Turkey based on full and unrestricted technology sharing. KAI won the contract for 45-60 T-50 jet trainers (developed with help from Lockheed-Martin) over U.S., Brazilian and Swiss bids. The latter was hampered by a Swiss decision to open political debate on the Armenian genocide claims, while the U.S. bid suffered from restrictions on technology transfers. According to KAI’s James Park; “We are prepared to provide the Turkish industry with unlimited technology transfer, which should help Turkey’s future indigenous aviation programs… We can share our experience in these programs with Turkish companies like TAI, Havelsan, Aselsan and others” (TDN, October 26, 2005).

INTO THE FUTURE

Gathering Intelligence by Satellite

The $250 million Gokturk Satellite project represents a significant effort by Turkey’s defense establishment to provide an independent solution to its intelligence needs that is not reliant on the political winds. Designed as a surveillance and reconnaissance satellite, Gokturk will be produced within Turkey under license. One of the main purposes of Gokturk will be the detection of terrorists crossing the Turkish border. It will also have a number of civilian uses, such as mapping, forest control, detecting illegal construction and assessing damage after natural disaster (Anatolia, April 4, 2008; see also Eurasia Daily Monitor, June 4, 2008).

Deployment of Gokturk will relieve Turkish reliance on U.S. and Israeli satellite data and the limited information available from its commercial satellites. The contract specifies that the satellite must be able to collect high-resolution intelligence data over any part of the world, without restriction. A bid by Israeli Aerospace Industries (manufacturers of the Ofek [Horizon] spy satellite) already appears to have fallen by the wayside over state-required restrictions over Israeli airspace (EDM, December 6, 2007; Today’s Zaman, December 6). Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak visited Ankara in February 2008 in an apparently unsuccessful effort to revive the deal. Political reluctance to deal with Israel has at times manifested itself in severe criticism of Israel’s Palestinian policies, especially under the AKP government of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Israel’s unsuccessful 2006 invasion of southern Lebanon and their “disproportionate response” to Qassam rocket attacks from Gaza have opened a deep rift with the Turkish public. It would seem normal at this point to predict there is little chance that Israel will be the beneficiary of many major arms contracts in the near future, but the ongoing Heron UAV deliveries and the Israeli upgrade of Turkey’s M60-A1 tanks suggest a certain latitude and pragmatism still dominates the assignment of Turkish defense contracts. (Haaretz, January 24, 2008; EDM, February 13, 2008).

Turkey has been unable to decide between the remaining three satellite contractors, Italy’s Telespazio, Germany’s OHB-System and British EADS Astrium. The British and Italian bids have been tainted, in Turkish eyes, by their inclusion of French partners – France recognized the “Armenian genocide” in May 1998, earning deep Turkish disapproval. The French decision was responsible for the scrapping of an earlier satellite project with French communications company Alcatel. Disagreements between the TSK and SSM over the current bids continue to hold up the project (Today’s Zaman, April 10).

CONCLUSIONS

A number of significant trends can be identified that are actually developing hand-in-hand:

- A still mostly state-controlled Turkish defense industry has benefitted from government efforts to make Turkey a major international arms exporter but there remains a possibility that efforts at consolidation may result in a lack of competitiveness.

- “Offsets” in Turkish production contracts and an ability to produce beyond Turkey’s substantial needs permit the growth of an export trade in arms.

- Government regulated reinvestment of profits from the export trade allows steady growth in the arms industry.

- Licensed production of arms and military equipment is regarded as a stepping-stone to the production of indigenous designs.

- Involvement in consortiums allows Turkey to become involved in the production of the major arms systems it requires to remain battle-ready and inter-operational with its NATO allies in a conventional war.

- Joint production through consortiums is at the same time regarded as less desirable in cases other than those above as it has not had the expected effect of upgrading the Turkish defense industry.

- Reforms to the old conscript army are designed to create a better-trained professional army capable of greater reliance on new (and preferably indigenously made) military technology.

- There is a greater emphasis on producing or obtaining arms and equipment that will aid in countering asymmetric threats such as terrorism or insurgency.

- There is no longer a preferred source for this equipment – Turkey is ready to buy battle-proven arms from anyone willing to provide them without restrictions (and especially those who don’t use their national legislatures to debate Turkish historical issues).

- Increased sharing of intelligence from the United States is not being taken for granted, as shown by Turkey’s efforts to develop new intelligence sources of its own, e.g., UAVs and military satellites.

- Technology Transfer is a major and often decisive requirement in most Turkish contract tenders for military arms and equipment.

- The Turkish defense establishment is pushing the Turkish arms industry in the direction of independent production of high-tech weapons.

- The choice of the Agusta-Westland Mangusta helicopter demonstrates that the TGS is no longer the dominant partner in the civil-military controlled SSM, Turkey’s military procurement agency.

- Embargos and like restrictions have compelled Turkey (like many others in similar situations in the past) to seek self-reliance in arms projects. Necessity has jump-started Turkey’s weapons development program successfully enough to allow the state to entertain ambitions of becoming a major global arms supplier.

Turkey’s drive for self-sufficiency in arms has brought about administrative, financial, political and military reforms designed to enable Turkey to remain a regional power capable of independent action outside its borders if it feels its national integrity is threatened. New directions are being explored in the fields of research, development and procurement to not only make Turkey self-reliant, but to allow it to become a major international arms supplier.

The drive for self-sufficiency in arms should by no means be interpreted as a trend towards military isolationism. Turkey continues to value its alliances and recognizes that international cooperation is the quickest path to victory in any conflict. Disputes with its European defense partners originate not in an unwillingness to cooperate, but a perception that Europe does not take Turkey’s security concerns seriously enough and is hesitant to fully integrate Turkey into European defense structures. New agreements with the United States on intelligence-sharing are a major step in alleviating suspicions within the Turkish military command about the sincerity of American rhetoric on the “global war on terrorism.”

Though concerns remain in Ankara about the future of Turkey’s relations with Greece, its long-time adversary and simultaneous NATO ally, Turkey’s priorities in arms procurement are now directed to the TSK’s deployment in southeastern Turkey. Here the military struggle is a classic example of asymmetric warfare, in which a proportionately smaller and weaker opponent (in this case the PKK) attempts to exploit perceived weaknesses in a larger and better armed adversary. The PKK’s strengths have been knowledge of the terrain, refuge in bases located across international boundaries, a willing supply of new recruits who identify with an ethnic/nationalist program, and the availability of propaganda outlets outside the control of the dominant power. Following decades of military successes that have had little effect on the continued existence of the PKK, Turkey has lately begun to find means of countering the PKK’s asymmetric advantages. Superior intelligence from Turkish unmanned aerial vehicles and American satellites have removed the PKKs ability to move about unobserved, improved relations with the Kurdish authorities of northern Iraq have permitted unopposed cross-border strikes on previously safe PKK bases and the initiation of new economic and social programs in ethnic-Kurdish southeastern Turkey hold the promise of drying up PKK sources of manpower. The existence of PKK propaganda outlets in places like Belgium and Germany is proving more problematic, but given that the aforementioned problems seemed insurmountable not long ago, there is hope that this difficulty may also be addressed to Turkey’s satisfaction in the near future.

Acronyms:

AKP: Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi – Justice and Development Party

DSCA: Defense Security Cooperation Agency (U.S.)

ESDP: European Security and Defense Policy

EU: European Union

FMS: Foreign Military Sales program (U.S.)

GENESIS: Gemi Entegre Savab Ydare Sistemi

IAI: Israeli Aircraft Industries

IBDA-C: İslami Buyukdogu Akıncılar Cephesi: Great Eastern Islamic Raiders’ Front

ISAF: International Security Assistance Force (Afghanistan)

JGK: Jandarma Genel Komutanligi: Gendarmerie General Command

JSF: Joint Strike Fighter

KKK: Kara Kuvvetleri Komutanligi: Land Forces Command

LANTIRN: Low Altitude Navigation and Targeting Infrared for Night

MILGEM: Milli Gemi – National Ship Project

MKEK: Makina ve Kimya Endüstrisi Kurumu (Mechanical and Chemical Industries Corporation)

MLRS: Multiple Launch Rocket System

PKK: Partiya Karkere Kurdistan – Kurdistan Workers Party

ROCKETSAN: Roket Sanayii ve Ticaret A.S.

SAM: Surface-to-Air Missile

SGK: Sahil Guvenlik Komutanligi – CGC: Coast Guard Command

SSIK: Savunma Sanayii Icra Komitesi: Defense Industry Implementation Committee

SSM: Savunma Sanayii Mustesarligi (SSM) – Ministry of National Defense Undersecretariat for Defense Industries

TAFC: Turk Hava Kuvvetleri: Turkish Air Forces Command

TAI: Turkish Aerospace Industries

TDF: Turkish Defense Fund

TDK: Turk Deniz Kuvvetleri: Turkish Naval Forces

TFLC: Turkish Land Forces Command: Kara Kuvvetleri Komutanligi (KKK)

TGS: Turkish General Staff: Turk Genelkurmay Baskanligi

TLF: Turkish Land Forces

TNFC: Turk Deniz Kuvvetleri: Turkish Naval Forces Command

TSK: Turk Silahli Kuvvetleri – Turkish Armed Forces

TSKGV: Turk Silahli Kuvvetlerini Guclendirme Vafki: Turkish Armed Forces Foundation

TUSAS: Turk Ucak Sanayi Sirketi – TAI since April 5, 2007

UNIFIL: United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon

WEU: Western European Union

WMD: Weapons of Mass Destruction

Chief of the Turkish General Staff Ilker Basbug

Chief of the Turkish General Staff Ilker Basbug Gendarmerie Colonel Cemal Temizoz

Gendarmerie Colonel Cemal Temizoz