Andrew McGregor

July 28, 2011

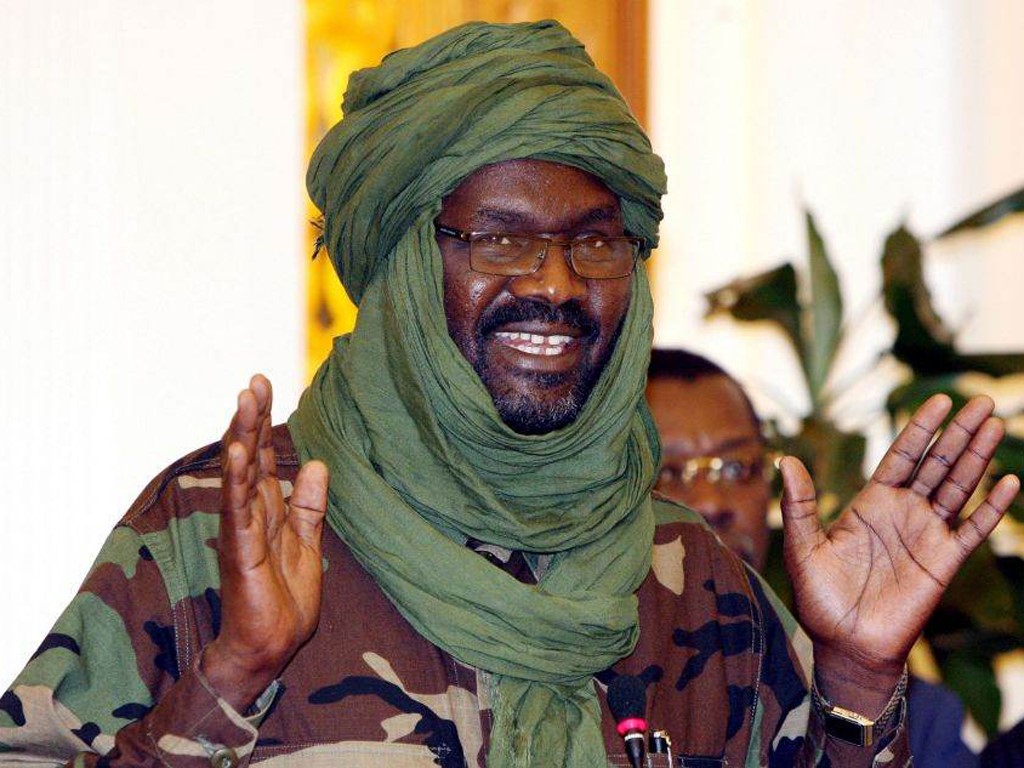

After several weeks of conflicting reports from Khartoum regarding the presence or absence of fighters from Darfur’s rebel Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) in the Sudanese state of South Kordofan, a military spokesman has announced the capture of a leading JEM commander, Brigadier General al-Tom Hamid Toto, in a battle between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and a combined force of JEM rebels and Nuba rebels of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) (for the war in South Kordofan, see Terrorism Monitor, July 1).

JEM Fighters: A Highly Mobile Force

SAF spokesman Colonel al-Sawarmi Khalid Sa’ad said the JEM commander would soon face trial in Khartoum. The official Sudan News Agency (SUNA) quoted the JEM Brigadier confirming his arrest, which he said happed after his vehicle was destroyed by shelling, during which he sustained a head injury. Toto added that his force had received logistical support from the Government of South Sudan (GoSS) during the JEM incursion into South Kordofan (SUNA, July 21).

A combined SPLA/JEM press release later confirmed the capture of three fighters, including two commanders, Brigadier Toto and Commander A. Zaki. The joint force reported overrunning the SAF garrison in al-Tais (25 km south of the state capital of Kadugli) in a battle that lasted from July 10 to July 17, killing 150 SAF troops and seizing large quantities of light and heavy machine guns, artillery, RPGs and anti-aircraft missiles. The statement also warned the prisoners must be treated as prisoners of war, a status Khartoum has routinely denied to JEM fighters [1] After earlier denials, the battle and the capture of Brigadier Toto led to an SAF admission that it was indeed fighting JEM units in South Kordofan, but said the rebel alliance would make little difference to the region’s balance of power (Sudan Tribune, July 18). The commander of the SAF’s 5th Brigade, Fadl al-Mula Muhammad Ahmad, claimed that government forces had “inflicted enormous losses of life and property” on the joint JEM/SPLA forces at al-Tais (Sudan Tribune, July 22).

Though Khartoum seemed reluctant to admit JEM was again operating in Kordofan, the chief of Sudan’s Joint General Staff, Lieutenant General Ismat Abdul Rahman Zain al-Abdin, claimed that the SAF had anticipated the revolt of the Nuba SPLA in June by learning of a plan to ally the Nuba fighters with a rebel faction from Darfur prior to announcing the confederation of South Kordofan with the new state in South Sudan (Sudanese Media Center, June 27).

JEM has lately been threatening to mount a new attack on the national capital of Khartoum. Elements of a massive 2008 long-distance desert raid reached the suburbs of Omdurman (Khartoum’s sister city on the west bank of the Nile), but fizzled out there under counter-attacks by local security forces before entering Khartoum proper (see Terrorism Monitor, May 15, 2008).

JEM has also made several raids from Darfur into Kordofan since 2006:

- JEM forces joined other Darfur rebels in a raid on Hamrat al-Shaykh in Northern Kordofan in July 2006 (al-Sahafa [Khartoum], July 4, 2006).

- On August 29, 2007, four columns of JEM fighters seized a Sudanese military base at Wad Banda (West Kordofan) for several hours, killing at least 41 SAF troops and taking large quantities of weapons and ammunition (SUNA, August 31, 2007, Sudan Tribune, August 31, 2007; see also Terrorism Focus, September 11, 2007).

- In October, 2007 JEM seized Chinese-operated facilities at the Defra oil field in South Kordofan as a warning to China to cease its support for Khartoum (Reuters, October 25, 2007; October 29, 2007).

- A JEM force attempted to take Chinese oil facilities at al-Rahaw (South Kordofan) in November 2007. JEM claimed to have taken al-Rahaw, but the SAF claimed they were driven off.

- JEM officials said the local Arab Missiriya had joined them in a December, 2007 raid on the Heglig oil field in South Kordofan, the most important oil field in Sudan (Reuters, December 11, 2007).

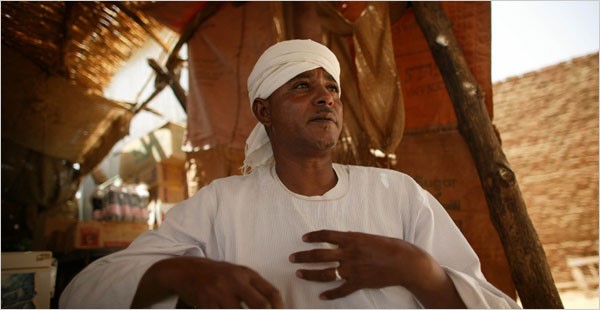

Though Khartoum professes to be unworried, it is almost certain that there is major concern in the capital over a possible alignment between JEM and the Nuba SPLA or the GoSS, which now has one of the largest armies in Africa. Khartoum has hinted at such a development for years and was likely alarmed by the appearance of a high-level JEM delegation in Juba during the July 9 South Sudan independence celebrations. The JEM leaders held talks with SPLM (Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – the political wing of the SPLA) leaders and conveyed a written message from JEM leader Dr. Khalil Ibrahim (Sudan Tribune, July 10).

JEM and the other major rebel movements in Darfur have abstained from the Doha peace talks, which Khartoum says will be the last opportunity for negotiations. The head of the government delegation at Doha, Dr. Amin Hassan Omar, claimed on July 22 that JEM leader Dr. Ibrahim Khalil had been arrested by Libyan intelligence (Radio Omdurman, July 22). Though this has not been confirmed, Khalil had been staying in Libya after being expelled from Chad when N’Djamena and Khartoum agreed to stop hosting each other’s rebel movements in January 2010 (see Terrorism Monitor Brief, January 21, 2010). Last February, the movement appealed to the United Nations to rescue the JEM leader from Libya, saying his life was in danger as a result of Khartoum’s allegations that JEM fighters were acting as mercenaries in Qaddafi’s military (Reuters, February 28). [2]

Note

1. “Joint JEM/SPLA Forces defeat SAF in South Kordofan: A Military Statement,” http://www.sudanjem.com/2011/07/52292/

2. See Andrew McGregor: “Update on African Mercenaries: Have Darfur Rebels Joined Qaddafi’s Mercenary Defenders?” Jamestown Foundation Special Commentary, February 24, 2011, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=1082

This article was originally published in the July 28, 2011 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.