Andrew McGregor

March 18, 2011

Speech delivered to the Jamestown Foundation Conference – “The Impact of Arab Uprisings on Regional Stability in the Middle East and North Africa,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington D.C, March 18, 2011.

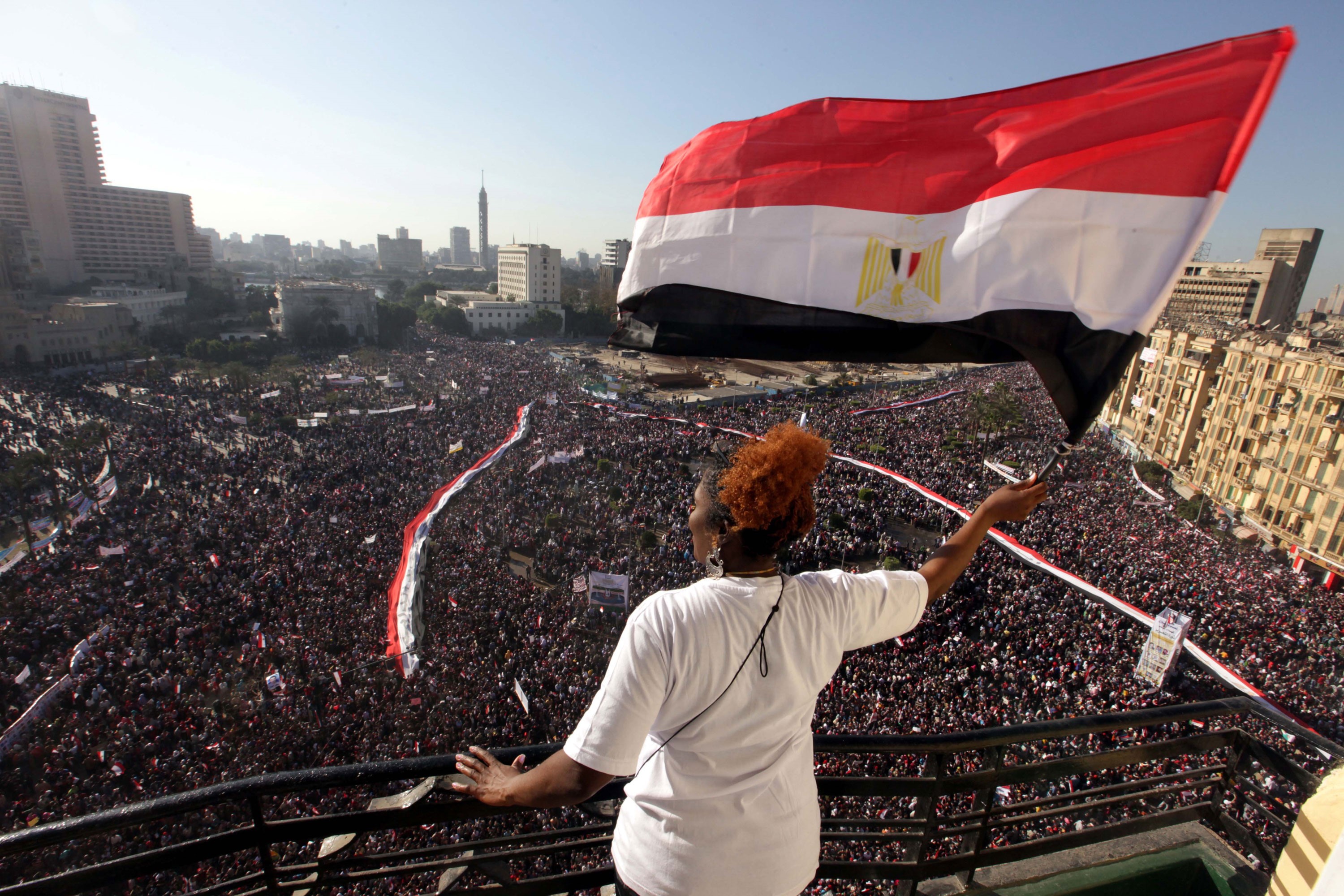

Storming the Bastille – Revolution in France, 1789

Storming the Bastille – Revolution in France, 1789

Introduction

Nostradamus himself could not have foretold the wave of political change that has been unleashed on the Arab world, all sparked by the self-immolation of a single Tunisian sidewalk vendor who could not find any other way of expressing his indignation at a corrupt and authoritarian system.

Revolutions are dangerous creatures that can unleash all kinds of unpredictable social forces that can take a revolution a long way from where it started.

The French Revolution of 1789, which both inspired and terrified Europe, began with the journées, days of mass action much like the “days of anger” we see today in the Arab world. Though the king and queen were led to their death, it was not long after that leading revolutionaries such as Robespierre had their own meetings with Madame Guillotine. Liberty, Fraternity and Equality became a mere slogan as Napoleon Bonaparte, the revolution’s leading general, restored authoritarianism to France and directing the slaughter of a generation of young men in pursuit of imperial conquest.

The European Revolution of 1848 and the Arab Revolution of 2011

In its size, sudden development and transnational character, the Arab Revolution most closely resembles the revolutions that shook Europe in 1848. There were many similarities, including:

- A rapid spread from country to country, despite each nation’s revolution having a different character and circumstances

- The revolts crossed social boundaries, even attracting an often reluctant middle class

- Governments appeared to cave in at first

- Too many university graduates were pursuing too few jobs. Higher education actually left them without the skills to pursue other types of employment

- No charismatic leader emerged along the lines of a Bolivar, Garibaldi, Castro or even Washington.

The Results of the 1848 Revolutions?

- Small concessions from the governments led to dwindling interest in revolution

- When the casual revolutionaries gave up, the revolutions were doomed

- The revolutions came to be dominated by a single political perspective (in this case, the left)

- By the summer of 1848, the forces of counter-revolution had time to reorganize and began clearing the barricades with the loss of thousands of lives

- The revolts in Hungary and Italy became larger wars of national liberation, but within one year both had been solidly defeated by the Hapsburgs

- In France, the Second Republic was soon replaced by the Second Empire of Louis-Napoleon.

In the end, all of the national revolts failed, but they laid the foundation and provided the inspiration for later revolts such as the Paris Commune of 1871 and the Russian Revolution of 1917. Most importantly, they signaled that the end of absolute monarchies was in sight. In this sense, even failed revolutions can have an enormous impact on political developments decades later.

Arms for Africa

It has been suggested in some quarters that the military weakness of Libya’s rebels can be overcome with supplies of modern weapons. It must be noted, though, that every influx of arms into the Sahel/Sahara region in the last century has been followed by years of violence.

It was an influx of arms that contributed to the breakdown of order in Darfur that eventually resulted in tens of thousands of dead. Darfur used a centuries old inter-tribal resolution system usually involving compensation in cash or animals to deal with incidents of violence such as murder. However, this system broke down when the introduction of automatic weapons allowed the slaughter of dozens of people at a time by a single individual. Traditional methods of maintaining peace and security were simply overwhelmed by advances in killing technology.

Arms may be the solution to Qaddafi, but they will not bring stability to North Africa. Those advocating the shipment of modern arms to Libya’s rebels speak of controls over whose hands they wind up in. This, however, is wishful thinking. Once introduced, arms are sold, abandoned, lost, stolen, surrendered, or given away. Reports that anti-aircraft missiles taken from the armories of eastern Libya have already found their way to the hands of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb should give pause to those backing a military solution to the Libyan insurrection.

Libya – Key to African Security or African Chaos?

The half-hearted endorsement of a no fly zone by the Arab League was taken by NATO as a green light for attacks on Qaddafi’s forces. In reality, with the exception of wealthy but distant Qatar, most of the Arab League has kept a committed distance from the conflict. Egypt, with its own internal crisis that has largely disappeared from the news, appears unable or unwilling to exert influence on the events in Libya. To the west, there are unverified rumors that Algeria’s own military-based regime is providing arms and aid to Qaddafi. Algeria has no desire to see the Arab revolution wash up on the shores of Tripoli, and giving the Libyan rebels a bloody nose would go a long way to discouraging like-minded dissidents in Algeria.

In neighboring Chad and Sudan two other political survivors, General Idriss Deby and Field Marshal Omar al-Bashir, will not be hasty in counting out Qaddafi. Both nations have deep if turbulent ties with Libya, which has fluctuated between assisting their development and interfering in their internal affairs. In the meantime both are keeping their distance, but if Qaddafi falls it is likely that both will attempt to exert their own influence on the formation of a new regime.

Qaddafi’s Desert Alternative

The fall of Tripoli would not necessarily mean the end of Qaddafi or his regime. The Libyan leader would have the option of retiring on military bases in the desert where he enjoys solid support. With access to fighters from neighboring countries, Qaddafi or his successors could continue low-scale but debilitating attacks on Libya’s oil infrastructure that would effectively prevent any new Libyan government from getting off the ground without substantial foreign aid and assistance. It would not be difficult to raise a tribal force opposed to what would be seen as a Benghazi-based government intent on depriving the western and southern tribes of power, influence and funds. Such a conflict could go on for years, with predictable effects on oil prices. The rebels do not have the means, and possibly not even the inclination, to distribute oil revenues throughout the larger Libyan society.

Should Qaddafi feel he is losing his grip on Libya it is possible that he could turn to asymmetrical warfare by once again sponsoring international terrorism, especially with strikes against the Western nations leading the attack on his regime. We also have no reason to suppose that a rump government in Benghazi would be a force for restoring security in the region. The rebels lack a trained security force or any kind of administration with a common goal other than the removal of Mu’ammar Qaddafi.

The al-Qaeda Question

The question here is not whether al-Qaeda will want to take advantage of instability in North Africa, but whether it can operate in any meaningful way.

Egypt is the historical crossroads of the world and as such it is an appealing theater of operations for al-Qaeda, which has ideological roots there through the works of Ibn at-Taymiyya and Sayid Qutb. Al-Qaeda could certainly attempt to penetrate Egypt and resume operations there, a course that would definitely appeal to Ayman al-Zawahiri and the other Egyptians in exile that form much of core al-Qaeda. However, al-Qaeda does not appear to have any active cells in Egypt, or even many sympathizers. There is little appetite for a return to the dirty backstreet war between Islamist extremists and the regime in the 1990s. More importantly, most Egyptians recognize that instability equals poverty, that terrorism isolates Egypt from the international community, depriving them of markets and important sources of foreign currency.

Al-Qaeda still does not present a political alternative developed beyond slogans promising the establishment of a Caliphate and the implementation of Shari’a law. With insufficient agricultural production, a rapidly increasing population, massive unemployment and underemployment and threats to its water supply that pose dangers to cultivation and power supplies, Egypt is in need of more thoughtful strategies than those supplied by the extremists. There are many sincere Muslims in the region who desire Shari’a, but they would also be the first to question the wisdom of leaving this in the hands of the band of kidnappers, murderers and drug traffickers that make up al-Qaeda in North Africa.

Opportunities will nevertheless be presented for al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb from the conflicts that will inevitably follow revolution. Attention and resources will be diverted from their activities, while arms and alliances will become available to strengthen their position.

Sudan – Darfur

Cobbled together from scores of ethnic and tribal groups speaking hundreds of different languages, Sudan, unsurprisingly, has been a center of dissent, rebellion and outright civil war from its first day of independence. While popular revolts may be something new along the Mediterranean coast, Sudan’s people have already overthrown two dictators (Ibrahim Abboud, 1964; Ja’afar Nimeiri, 1984).

With the conflict in Darfur continuing despite a decline in foreign or media interest, and a number of unresolved issues threatening the peaceful separation of the south from the north, Sudan is now faced with the possibility of further disruptions to security arriving from its northern neighbors of Egypt and Libya. Qaddafi’s Libya has actually played a vital role in negotiating a peace settlement in Darfur and it is uncertain who would step up to fill the void. A small protest movement in Khartoum has been firmly repressed so far, but there is enormous dissatisfaction in the North with President Omar al-Bashir, who has failed to keep the country together and has lost most of its oil revenues to the new southern state. In the current situation there is the possibility of both North and South Sudan turning into failed states with enormous consequences for a large part of Africa.

The Tuareg – What Will They Do After Libya?

The collapse of the Qaddafi regime will have an enormous impact on the states of the Sahara and Sahel, including Chad, Mali and Niger. Libya is an integral part of the economies of many of these states, both through financial donations and the employment of hundreds of thousands of migrant workers from these countries. Qaddafi regards this region as the Libyan hinterland and has played in important if sometimes destabilizing role in the area, particularly through his recruitment and sponsorship of the Tuareg peoples, whose ancient homeland has been divided between half a dozen nations in the post-colonial era. Having long acted as a kind of sponsor for the activities of Tuareg fighters battling regimes that regard the Tuareg presence as inconvenient and undesirable, Qaddafi is now arming Tuareg warriors who are rallying to his cause. Regardless of whether Qaddafi wins or loses, there is immense concern in these nations that the Tuareg fighters will return to their home states to initiate a new round of rebellions in poorly secured but oil and uranium-rich regions.

What Direction for Egyptian Security?

The Egyptian Revolution is not yet history. In fact, we may only have witnessed the first phase of a process that could continue for years or even decades. It is unlikely that Egypt’s officer corps, unquestionably part of Egypt’s elite, is willing to oversee the transfer of power from that same well-entrenched elite to the masses. Indeed, it would be unreasonable to think that this would be their first instinct. In Egypt, political revolution is also social revolution, and these things don’t usually happen overnight.

Egypt’s internal security services collapsed in the wake of the Egyptian Revolution and are in the difficult process of being rebuilt and restructured with a new mandate that promises to pursue genuine security threats rather than internal political opposition.

While there were many cases of government violence against demonstrators, there were remarkably few incidents of retaliatory violence against members of the security services during the revolution. Egypt does not have a taste for violent revolution. Such matters are traditionally handled by the nation’s elite, now formed from the military leadership.

The question here is how effective will a restructured security service devoted, as promised, to foreign rather than internal threats will be in controlling extremists. Egypt managed to destroy its radical Islamist movement by deploying an Interior Ministry force three times the size of the military, aided by legions of informers, both paid and coerced. Securing Egypt from Islamist extremism has come at a considerable cost to the liberty of most Egyptians, a cost no longer considered acceptable. The question, however, is whether a lighter and less-intrusive security presence still be as effective in eliminating Islamist extremism.

Unforeseen Consequences

Qaddafi’s Libya has always been one of the major financial backers of the African Union. These donations have stopped now with significant consequences for the African Union Mission in Somalia, which already suffers from underfunding. There is no guarantee a new Libyan regime would renew such support, nor is it likely another African state would be able to step in to fill the shortfall.

Sub-Saharan countries have been effectively excluded from partaking in the resolution of the Libyan conflict, even though they will inevitably be affected by what happens in Libya and, moreover, have close ties and influence with Libya. The African Union negotiations were treated as an unimportant sideshow by the nations busy taking out Libya’s armor and air defenses. At some point the West will have to shrug off a self-assumed “White Man’s Burden” that has become outrageously expensive and deeply destabilizing. While it is true that African Union diplomatic and peacekeeping missions have an uneven record, it is also true that African troops aren’t going to get any better at this kind of thing by sitting in their barracks. More cooperative efforts between the West and Africa that acknowledge the interests of those actually living in the continent and the limitations of external parties would do more to stabilize North Africa than a hail of bombs and rockets.

Conclusion

In short, revolution is not an easy thing – most fail, and it would be presumptuous to assume that revolts in Egypt or Libya or the Middle East will lead to inevitable success, regardless of how this success is interpreted. However, whether successful or not, their repercussions can rarely be tamed, making them recipes for insecurity. At best they can be managed, with a bit of luck. At worst, efforts to contain or reverse social and political transformation are only capping the volcano – if it doesn’t erupt there, it will erupt somewhere else, at a time of its own choosing.