Andrew McGregor

October 28, 2010

Over half the world’s kidnappings for ransom occur in Latin America, however, among these nations only Mexico and Colombia merit official U.S. travel advisories that mention the danger of kidnapping. Despite this, Mexico and Colombia continue to enjoy thriving tourist industries. Yet the African state of Mali, with only a handful of such kidnappings each year, has been afflicted with similar travel advisories, not only from the United States, but from other Western nations as well that have devastated a nascent tourism industry with enormous potential. The difference? Al-Qaeda.

Mali’s Military: Up to the Job?

Mali’s Military: Up to the Job?

With an economy based on agriculture and gold production, Mali is one of the poorest nations in the world. The development of a tourism industry based on the growing popularity of Saharan tourism (particularly in European markets) promised a new economic sector, a source of foreign currency and a potential solution to the unrest in Mali’s Saharan north, which is largely based on lack of economic opportunity. To the disappointment of Mali’s government, this growing economic sector has come to a halt due to the criminal activities of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), whose Southern Command now focuses on drug trafficking, smuggling and high-profile kidnappings for ransom. The tourism industry of some regions of the north is now operating at only 10-15% of capacity.

On October 15, Mali’s Minister of Tourism and Crafts, N’Diaye Ba, complained of what might be termed “the al-Qaeda effect,” or the disproportional damage caused by even the limited presence of Islamist terrorists:

While it is undeniable that some events that took place in the Sahel-Saharan strip incite prudence to avoid endangering the lives of visitors, it’s equally evident that a zero risk exists nowhere in the world… The use of the terrorist menace, which gives free publicity to the terrorists, seems like a fearful weapon to compromise all the prospects of development of a place, a region, a country (AFP, October 15).

Since al-Qaeda took advantage of Mali’s weak security infrastructure to establish bases in the vast desert wilderness of the country’s north roughly two years ago, Mali has entered a situation in which the presence of the terrorists prevents the economic development that would convince tribal elements in the north (particularly the Arab tribes and to a lesser degree, the Tuareg) from joining or doing business with AQIM units that are rolling in cash as a result of collecting enormous ransoms (estimates vary from 70 to 150 million Euros in total) based on their fearsome reputation.

International vs. Regional Solutions

Malian President Amadou Toumani Touré says that Mali is both “a hostage and a victim” of AQIM: “These people [i.e. AQIM] are not Malians. They came from the Maghreb with ideas that we do not know. The problem is the lack of regional cooperation. Everyone complains about their neighbor…” (Ennahar [Algiers], October 1). Mali’s government has declared a series of measures designed to deal with the concerns about its security:

• A rational occupation of territory by the state administration.

• Increased mobility on the part of troops for prevention and intervention.

• A social mobilization to reduce the influence of sects and criminal groups (AFP, October 15).

The G8’s Counter-Terrorism Action Group (CTAG) held a two day meeting in Bamako in mid-October to discuss the AQIM threat. President Amadou Toumani Touré told the meeting that security alone could not resolve the AQIM issue, saying that development of the Sahel region is necessary to undercut support for militant groups (AFP, October 14). Though the meeting was also attended by representatives of the African Union (AU), the UN, the EU and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), its success was hampered by the absence of Algeria, which refused to attend due to the presence of Moroccan representatives (Le Républicain [Bamako], October 14; Ennahar [Algiers], October 13; AFP, October 13). Tensions between the two states remain high due to disagreement over the status of the Western Sahara.

Malian Colonel Yamoussa Camara said in the meeting that foreign forces should avoid operations in Mali and limit themselves to providing training and equipment to Mali’s armed forces to prevent the latter from losing popular support (AP, October 13). There were complaints in Mali in September that Mauritanian troops were operating against AQIM in the north of the country while Mali’s own troops were busy with parades celebrating the 50th anniversary of independence (Jeune Afrique, October 9). Colonel Camara’s remarks were echoed a week later by Algerian Minister of Foreign Affairs Mourad Medelci who said foreign military operations in the area are undesirable. According to Medelci, “We are responsible for security, as the Sahel, of all who live in the area where the situation is worrisome… Algeria has never said that countries that are not part of this area were not affected [by terrorist activities]. If these countries can provide assistance, they are welcome but they cannot establish themselves among us to bring the solution” (Ennahar, October 22).

Mali’s insistence that regional cooperation is the key to solving the AQIM dilemma must overcome significant distrust between many of the countries of the Sahel/Sahara region. Besides the seemingly intractable diplomatic conflict between Algeria and Morocco, there is also suspicion of the motives and activities of Libya’s Muammar Khadafy. Even inside Mali, there are misgivings regarding the sincerity of Algeria’s counterterrorism efforts; according to numerous reports circulating in Mali, the last words of Colonel Lamana Ould Bou (a senior Malian security officer investigating AQIM activities in northern Mali before being gunned down in his home last June by unknown assailants) were, “The Département du Renseignement et de la Sécurité [DRS] is at the heart of AQIM” (al-Jazeera, August 29; Le Hoggar [Bamako], October 11). The Algerian DRS is widely believed to have infiltrated operatives into the DRS, with some suspicious Sahel observers even claiming AQIM is a false-flag operation run entirely by the Algerian intelligence service.

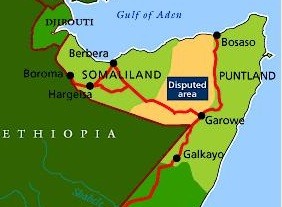

The question of allowing foreign military operations in Mali became more complicated when Mauritanian aircraft in pursuit of suspected al-Qaeda fighters killed two civilians near Timbuktu in September (Reuters, September 20). However, with little ability to control its northern region, Mali seems determined to avoid inflaming AQIM by allowing military forces of France (the former colonial power) to be based there (Le Monde, September 22). Mali does, however, accept military training from French forces and has a number of American Special Forces training teams stationed within Mali (see Terrorism Monitor Briefs, June 4). Nevertheless, based on the inability of Mali’s military to even refuel Mauritanian forces during a September 18 clash with AQIM in northern Mali, Algerian authorities have described Mali’s armed forces as “incompetent” (Jeune Afrique, October 15).

The Arlit Hostage Crisis

The latest crisis involves the kidnapping of seven Areva and Satom employees from the uranium mine at Arlit in northern Niger on September 15. The operation was carried out by the Tarek Ibn Ziyad katiba (military unit) led by AQIM commander Abd al-Hamid Abu Zaid (a.k.a. Abid Hammadou) (Le Monde, October 11). Five of the hostages are French; the other two are from Togo and Madagascar. Heavy fighting between AQIM forces under Algerian commander Yahya Abu Hamam and Mauritanian forces was reported shortly after the abductions (Ennahar, October 15; Jeune Afrique, October 9).

While this latest group of hostages is being held in northern Mali, there are denials from all sides that France ever requested permission to base troops or aircraft involved in the search on Malian territory, though this may be a sop to Bamako’s sensitivity on the issue. The air component of the search is thus based in Niamey in neighboring Niger, while French Special Forces are awaiting deployment in the Burkina Faso capital of Ouagadougou. The Kidal airstrip in northern Mali would be useful in the search, but would have the disadvantage of exposing French forces to direct attacks by AQIM (Jeune Afrique, October 9; Air & Cosmos [Paris], September 29; Le Monde, September 22). Not surprisingly, one of AQIM’s reported demands for the release of the hostages is a commitment from Bamako that further French and Mauritanian military operations will not be allowed on Malian territory (L’Indépendant [Bamako], October 12). When and if the time comes for a military intervention on Malian soil to save the hostages, it is expected that Bamako will look the other way until the operation is completed.

Is Regional Security Cooperation a Mirage?

As a result of the Tamanrasset meeting, a joint Sahel information center (Centre de Renseignement sur le Sahel – CRS) was established by the intelligence chiefs of Algeria, Niger, Mali and Mauritania in Algiers on October 7 to collect intelligence from the security services of the four nations and make it available to the new joint military operations center in Tamanrasset (L’Expression [Abidjan], October 7).

In April, Algeria, Niger, Mali and Mauritania formed the Tamanrasset-based Joint Operational Military Committee, designed to provide a joint response to border security and terrorism issues. Ten days after the Arlit abductions, the committee (composed of the military chiefs of the four nations) met on September 26 to establish a coordinated response against the AQIM threat. The committee is currently headed by Malian Brigadier-General Gabriel Poudiougou, but there is little enthusiasm in Bamako for the new security center in Tamanrasset, which is referred to at the highest levels of the government as “an empty shell” (Jeune Afrique, October 15).

The absence of Chad, Libya and Morocco from the new cooperative security infrastructure will certainly hinder efforts to eliminate AQIM from the region. The leaders of Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Mali and Chad held a consultative meeting on the sidelines of the Arab-African Summit in the Libyan city of Sirté on October 10, though this did not seem to ease the admission of new members into the four-nation Sahel security grouping. Mali’s efforts to broaden the group have been continually vetoed by Algiers. Earlier this month, however, Libya donated two much-needed Italian Marchetti surveillance aircraft to Mali to combat local unrest (AFP, October 4).

Despite the insecurity in its own northern region and the fact the Arlit hostages were seized in Niger before being moved to Mali, Niamey has been quick to identify Mali as the source of regional insecurity. According to Amadou Marou, president of Niger’s National Consultative Council (which is managing the country in the aftermath of February’s military coup), “Somalia got away from us and northern Mali is in the process of getting away from us” (AFP, October 15).

Conclusion

International crime statistics alone will not solve Mali’s dilemma, nor will claims that it is the object of a “disinformation campaign” (AFP, October 15). So long as AQIM can conduct one kidnapping or hold one hostage on Malian territory each year, it will, in the current perception that there is no kidnapper as deadly as an al-Qaeda kidnapper, prevent the necessary economic development of Mali’s northern region. To enable development, Mali is left in the unenviable situation of having to establish almost complete security in a vast region with precious few security resources or having to turn to foreign military forces to aid in the elimination of al-Qaeda elements – something these same forces have failed to achieve elsewhere. Mali, however, cannot disclaim any responsibility or involvement in the rash of AQIM kidnappings. A sophisticated network of mostly Malian negotiators and mediators has emerged, with these middlemen making enormous profits through receiving a cut of the ransoms. Some mediators are even believed to participate in the kidnappings and then act as negotiators (Info Matin [Bamako], October 14; L’Indicateur du Renouveau [Bamako], October 14; Daily Times [Karachi] October 12). There can be little doubt that, as with the Sahel/Saharan narcotics trade, some of these illicit funds are reaching senior levels of the political and military structure in Bamako. This does not make Mali unique among nations facing similar problems, but the lure of easy money in an impoverished nation represents a threat in itself.

One option being considered in the Malian capital to deal with the security threat is rearming and deploying Tuareg fighters (only recently disarmed after rebelling against the central government) to hunt down and eliminate al-Qaeda operatives. At present, Bamako faces a problem that is more criminal in nature than political or religious, but foreign intervention brings the immediate risk of escalation and an uncertain political future in the event of a popular backlash in Mali. Neither prospect promises a new era of stability, so Bamako will likely continue for now in its calls for a regional security cooperation that may be largely illusory due to the mutual suspicions of the Sahel/Sahara nations.

This article first appeared in the October 28, 2010 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor