Dr. Andrew McGregor

June 10, 2006

In recent years the Sudan government has been responsible for pouring weapons into Darfur at a time when territorial and environmental tensions were already high. Rather than encourage and supervise resolutions to these issues the government has chosen to inflame ethnic and racial divisions in the region. The well-known devastation created by this policy has a precedent in British activities in the region in 1915-16 as part of the buildup to the Anglo-Egyptian invasion that brought the independent Sultanate of Darfur under the control of the Khartoum government.

Anglo-Egyptian Rule in the Sudan

Darfur’s independence was first shattered by an invasion led by the powerful slave-trader and freebooter Zubayr Pasha in 1874. Zubayr’s conquest was quickly taken from him by the Turko-Egyptian government,[1] which controlled the rest of the Sudan at the time. The Egyptians in turn were expelled by the forces of the Mahdi, whose Islamic movement took control of most of the country except for a small strip of the Red Sea coast.

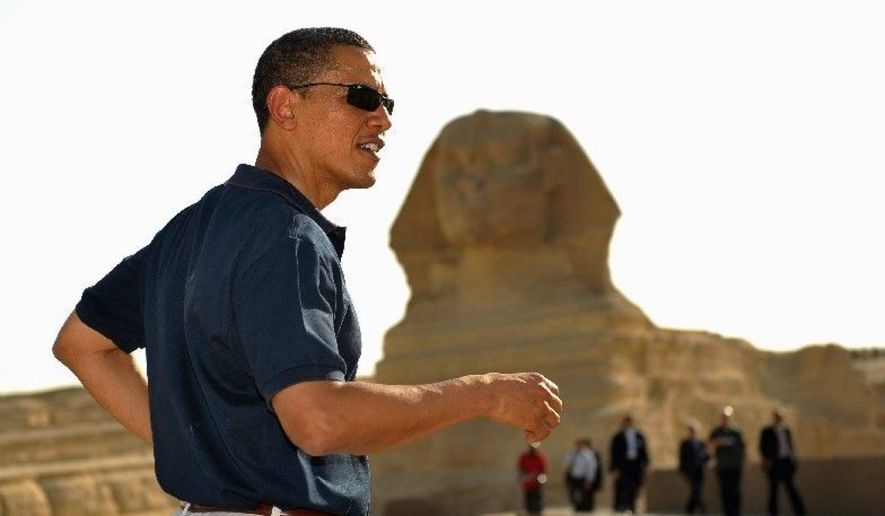

An Embassy from Sultan ‘Ali Dinar to Khartoum, 1907

An Embassy from Sultan ‘Ali Dinar to Khartoum, 1907

(Sudan Archives, Durham University)

After the Mahdist government of Sudan was crushed at Omdurman by the British-led Egyptian Army in 1898 a so-called British-Egyptian Condominium government was created to administer the Sudan. Though a partnership in theory, government decisions were made exclusively by the senior partner, the British. Units of Sudanese and Egyptian troops were available to enforce the government’s writ, but the senior officers were all British soldiers on loan to the Egyptian Army. The Governor General of the Sudan was also exclusively British, creating friction with Egyptian nationalists who justifiably questioned the balance of this ‘partnership’. Added to this were civilians of the Sudan Political Service, powerful and independent men who often worked in isolation from other Europeans for long stretches of time. Almost exclusively drawn from Oxford and Cambridge universities, they were fluent in Arabic and expected to make most decisions in the field without having to refer everything to the Governor General in Khartoum. For over five decades this low-cost and, indeed, low-interest, form of administration worked surprisingly well, in large part because of British willingness to apply overwhelming force to any sign of defiance, especially in the early days of the Condominium.

Darfur remained outside the Condominium. It had been intended that it would form part of the Sudan in 1898, but a member of the Fur royal family, ‘Ali Dinar, beat the British back to the capital of al-Fashir after the battle of Omdurman, deposing a British-supported pretender while re-establishing the Fur Kingdom. The British recognized ‘Ali Dinar as sovereign of distant Darfur in exchange for an annual tribute and a nominal acceptance of the Sudan Government as the suzerain power.

Most of the British inspectors were trained in Arab language and culture, and had little sympathy for what they saw as backwards and ignorant Black Africans, regardless of their skills or achievements. For the Fur these achievements were considerable. For three centuries they had ruled a prosperous trading nation with a rich culture, building political unity from a nearly impossible ethnic and linguistic diversity.

Creating Divisions

The Arabs were never enthusiastic about Fur rule, but the centralized authority of the region created a tense but workable relationship between the tribes and the Sultan, who had recourse to a large professional army. Tribute was usually paid, and a degree of order prevailed between African and Arab tribes who might otherwise raid each other to their mutual impoverishment. What had changed by the late 19th century was the encroachment of European imperialists, the French to the West, and the British to the East. The Arab leaders realized that they now had a new card to play by manipulating this presence to their advantage. A similar phenomenon occurred in the Sultanate of Dar Sila on Darfur’s western border, where the nomadic Arab tribes besieged the French with complaints about the ‘African’ Sultan Bakhit. The Sudan government’s relationship with Darfur began to change in 1914, when the British became interested in using the Arabs against the African tribes who dominated Darfur.

The security of the Darfur border region was placed in the hands of one of the Sultan’s most trusted lieutenants, Khalil ‘Abd ar-Rahman. Determined to put an end to the insolence of the Arabs, Khalil pursued an active policy of force against the tribes, creating an incident in 1913 when he attacked a large party of Zaiyadia Arabs fleeing the Sultan’s troops. The attack took place on the Kordofan (Sudanese) side of the border, causing a great deal of anxiety amongst the handful of British administrators who regarded this as a direct challenge to government authority in the region.

The problem was that there was no uniform policy in dealing with the Arab tribes, especially those that routinely crossed the border to seek refuge from the Sultan or the Khartoum government, depending on the circumstances. The generally pro-Arab inspectors were divided on the timing and degree of support to be offered to the Arabs, while the Inspector-General, Rudolf von Slatin Pasha (who knew ‘Ali Dinar from their mutual captivity in Omdurman during the days of the Mahdist government) favoured a conciliatory relationship with the Sultan. Before the Mahdist revolution Slatin had been governor of Darfur in the old Turko-Egyptian regime. Under the Condominium government Slatin was given nearly total control over the nomadic tribes and the appointment of their leaders, mostly men known personally by Slatin and regarded by him as loyal to the government.

With the outbreak of a European war in August 1914, the Austrian-born Slatin was expelled from the Sudan as a security risk despite having been a member of the Egyptian Army since 1879. No European had such intimate knowledge of the peoples of Darfur as Slatin. Tribal policy in the western Sudan now passed into the hands of less-experienced British officials. In November 1914 the Ottoman government declared war on the Allied Powers, followed soon after by a declaration of jihad for all Muslims by Ottoman Sultan Muhammad Rashad V in his role as Caliph of Islam. From this point on a religious dimension emerged in the deteriorating relations between ‘Ali Dinar and the Khartoum government. Governor-General Wingate (an experienced intelligence hand in the Egyptian Army) began to make funds available to the Kordofan inspectors to mount espionage and other secret operations against Darfur.

Preparing the Grounds for War

The Ottoman Sultan’s proclamation of jihad had no impact on the Arabs of Darfur. The bitter legacy of the Turko-Egyptian 19th century occupation of the region meant that the Arabs had no interest in supporting the Ottomans. The survival and growth of the tribe remained paramount, and the key to this was seen to be cooperation with the British.

With the Kababish Arabs raiding the eastern frontier of Darfur in 1915 the Sultan appealed to the Government for arms and ammunition to defend his territory, a natural request to make of the suzerain power. The Kordofan-based Kababish were the largest nomadic tribe in the Sudan. In 1911 they had been bold enough to strike into western Darfur to raid one of the Sultan’s own caravans carrying a large shipment of arms. The tribe’s loyalty was more important to the Khartoum government than ‘Ali Dinar’s satisfaction, so the Sultan’s request for arms was denied. In the end the British relented to sending 1,000 rounds, a ridiculously small amount. Larger considerations were at play here; ‘Ali Dinar had for years battled French encroachment on his western border and had repeatedly requested arms from the government, only to be denied in every case. The British did not wish to create an incident with their wartime French allies by giving a Fur army the means of defeating a French expedition.[2] The British and the French had already been negotiating the limits of the western border of Darfur before the war, but put off a decision until the war was over.

Rizayqat Herders (Dabanga)

Rizayqat Herders (Dabanga)

By May 1915 ‘Ali Dinar was sending threatening letters to the leader of the Kababish Arabs. He accused them of joining the infidels but suggested they follow the path of jihad instead. The Kababish chief, ‘Ali al-Tum, immediately dumped the letters on the closest British inspector with a warning that the government should take care of this ‘fanatic’. The British inspectors in Kordofan now began to realize the thinness of their rule, and broached the idea of a pre-emptory invasion of Darfur.

Governor-General Wingate and most of his fellow officers in the Sudan were refused in their applications to transfer to the fighting on the Western Front on the grounds of their experience and irreplaceability in the Sudan. These were all professional soldiers who began to realize that their own efficiency in keeping Sudan quiet during the war was cutting them out of the opportunities for promotion and decorations they could get in Europe. Once planted, the idea of creating a new battleground for the Great War began to take on steam. Rumours of German officers in al-Fashir and diabolical cruelties committed by the Sultan began to circulate. Eventually these rumours and other fantasies were all packed off to London labeled ‘Intelligence’.

Musa Madibbu and the Rizayqat

Normally Arab complaints of the Sultan’s hostility were grounded in the Arab tribes’ own prevarication in paying the annual tribute. Therefore the Government usually responded with a few words of sympathy and a suggestion to pay the tribute more promptly. In July 1915 the Governor-General instructed his agents to advise Musa Madibbu, chief of the Rizayqat tribe, to avoid paying the tribute, advice sure to result in fighting. It was thought that any government invasion of Darfur would benefit greatly from having the Sultan’s army ’embroiled with the Rizayqat’. Wingate, whose experience in intelligence work included what may be called ‘dirty tricks’, suggested that in his correspondence with the Sultan, Madibbu should name any supporters of ‘Ali Dinar in his own tribe as the individuals preventing him from collecting the tribute.

Musa Madibbu was interested in enlisting the aid of the Sudan Government in a growing struggle between his tribe and the Fur Sultan. In 1913 the Rizayqat had narrowly beaten a Fur punitive expedition, but losses were heavy and Madibbu did not believe the Rizayqat could duplicate their win. In September 1915 British Inspector John Bassett offered to loan the Rizayqat arms and ammunition to defend themselves from the Sultan. The total amount came to 300 rifles and 30,000 rounds, enough to turn the Rizayqat into potent challengers to Fur rule. In December a similar loan of 200 rifles and ammunition was made to ‘Ali al-Tum and the Kababish. Musa Madibbu had no intention of taking on the Sultan himself, however, and wrote to the Government that ‘we are poor Arabs and have no power to resist this man’. By this point both the Arabs and the Government were trying to manipulate each other. The dispute grew as the Sultan sent Musa Madibbu a pair of sandals to run away with, while Musa replied that he would soon be watering his horses at the Sultan’s capital of al-Fashir.

The new Government policy was a reversal of its long-standing efforts to disarm the Arab tribes of Kordofan. The region was still awash with 35-year old rifles seized by Mahdist fighters from the ill-fated Hicks Pasha expedition of 1883, but many of these had lost their sights or seen their barrels sawed off to make them easier to carry. Even those still intact commonly used pebbles for ammunition in lead-poor Sudan. The supply of modern weapons and ample ammunition was a dramatic change to the strategic situation in Darfur.

Nomadic Maelstrom

By April 1916 460 Arabs of the Kababish, Kawahla, and other Arab tribes had been deployed in a string of eight posts along the Darfur frontier. All were armed and paid by the Government. The Arabs were ordered to carry out scouting forays into Darfur, but, as one inspector wryly put it, ‘their vigorous interpretation of the term reconnaissance’ took them some 300 miles right across Darfur. The new British-supplied weapons were used by the Arabs to attack their old rivals in French territory, the Bidayat and the Gura’an. There were suggestions that a Government man be sent to the Arabs to reign in their excesses, but eventually it was decided it was better to look the other way, as a government representative would simply be a witness to ‘enormities’ that he could do nothing to prevent.

As the Egyptian Army crossed Kordofan ‘Ali Dinar sent a strange report to Sultan Muhamad Rashad in Istanbul that reflects his agitation and a great deal of wishful thinking besides:

We beg to inform Your Majesty that the Moslems who have abandoned Islam and embraced Christianity have been punished in a miraculous way never heard of on this earth – except during the time of the Prophets… It fell on a tribe called Rizayqat, subjects of ours who had abandoned the light of Islam and followed the advice of the Christians, the dogs – The heaven rained fire on them and they ran to the river and diving therein, turned into black coal – In another place Heaven rained red blood.[3]

|

‘Ali Dinar failed to meet the British at the border with his army, fearing that if he moved his troops up, Musa Madibbu would sweep in behind him and loot al-Fashir (presumably with those Rizayqat who had not been turned into coal). The Sultan now took on a more friendly tone in his communications with the Rizayqat chieftain. The Sultan announced that he was satisfied with Musa, and in a mix of threat and encouragement informed the Arab chief that the Fur army had already met the Anglo-Egyptian invasion force, and that though each of his men was hit at least ten times by the infidels’ bullets, there were no injuries.

In May 1916 the Sultan’s army was defeated at the battle of Birinjia, followed several months later by the Sultan’s own death at the hands of an Anglo-Egyptian mounted infantry task force. While this put an end to Fur resistance the nomads of Darfur were just getting started. By the middle of 1916 the nomadic African Bidayat, Gura’an and Zaghawa tribes were all raiding from French territory into northwest Darfur. ‘Ali al-Tum led the Kababish against the Berti in northern Darfur, defeating them and seizing their herds on the pretext that they were ‘enemies of the government’. From there they turned to raiding Dar Zaghawa (a territory straddling the Chad/Darfur border). At the same time the Bani Halba of southern Darfur were looting herds without any concern for whether their owners were pro or anti-government.

In October a raiding party of 200 Kababish was in the Ennedi region (modern north Chad) seizing women and children. In retaliation the Bidayat and Gura’an raided the Arabs of northern Darfur in November, then turned south to take 3,500 head of cattle and 50 women and children from the Fur. In December, 1916, a column of the Egyptian Army Camel Corps was sent to northwest Darfur to cooperate with French units against the Bidayat and the Gura’an. The provision of arms had unleashed a storm of retaliatory violence that the government had great difficulty reigning in over the next several years.

Conclusion

The Darfur campaign never achieved recognition as part of the Great War. This was a great disappointment to the expedition’s British officers, but designation as a part of the World War meant that London would be responsible for the costs of the conquest. Although the invasion was justified as a strike against German and Ottoman forces in Africa, the conflict received the official designation ‘Patrol 16 of the Egyptian Army’ making it a purely local affair. This revisionist slight of hand allowed the entire bill to be sent to Cairo instead.

In the end, the Arab tribes contributed almost nothing to the conquest of Darfur. The violence of raid and counter-raid swept across northern Darfur long after the campaign of 1916. Even the Great War had come to an end by the time French and British colonial officials cooperated to bring an end to the destruction of life and property. Like the current situation in Darfur the Sudan government had introduced modern arms into the region while aggravating ethnic and territorial conflicts that were usually resolved by traditional methods of conciliation. As the chaos spiraled out of control the colonial government (like today’s regime in Khartoum) chose to disclaim any responsibility. Unfortunately the lessons of history have little attraction for today’s policy-makers.

Notes

[1]. So-called since the entire ruling class of Egypt at the time was composed of Turks, Circassians, and other races of the Ottoman Empire. Turkish rather than Arabic was the language of both the elite and the military.

[2]. I have used the term ‘Fur army’ in this paper in reference to the Sultans’s forces, but the army was in fact composed of many different tribes and ethnic groups. The two senior commanders were both slaves from the southern hinterland, named Sulayman ‘Ali and Ramadan ‘Ali.

[3]. National Records Office, Sudan: NRO INTELL 2/2/11, pt.2; Letter from ‘Ali Dinar to His Majesty Sultan Muhammad Rashad, 1334 (1916)

This article first appeared on Military History Online, June 10, 2006, http://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/wwi/articles/subvertingthesultan.aspx#

The region is a strategically important territory with considerable mineral, gas and petroleum wealth. Little of the wealth now produced in Balochistan has found its way back into the province, which remains badly underdeveloped and faces a major financial crisis even as new natural gas discoveries continue. As a result, pipelines and other energy installations have been primary targets of Baloch nationalists. President Pervez Musharraf’s government has recently committed large sums for development projects, but some distrustful Baloch nationalists view these as further efforts at “colonization.”

The region is a strategically important territory with considerable mineral, gas and petroleum wealth. Little of the wealth now produced in Balochistan has found its way back into the province, which remains badly underdeveloped and faces a major financial crisis even as new natural gas discoveries continue. As a result, pipelines and other energy installations have been primary targets of Baloch nationalists. President Pervez Musharraf’s government has recently committed large sums for development projects, but some distrustful Baloch nationalists view these as further efforts at “colonization.” Balochi Fighter (Friday Times)

Balochi Fighter (Friday Times)