Andrew McGregor

May 4, 2006

Any observer of Yemen’s political scene cannot help but notice that Yemen appears to be awash with al-Qaeda suspects. Mass trials follow mass arrests as hundreds of suspects flow through Yemen’s legal system. Some are selected for execution and others for lengthy prison sentences, but many avail themselves of early release or periodic amnesties. The system seems designed to weed out those who present a direct threat to Yemen or its regime, while relieving U.S. pressure in the war on terrorism by offering a constant demonstration of activity. In the wings of this performance is the constant threat of an insurgency led by Yemen’s powerful Islamist movement.

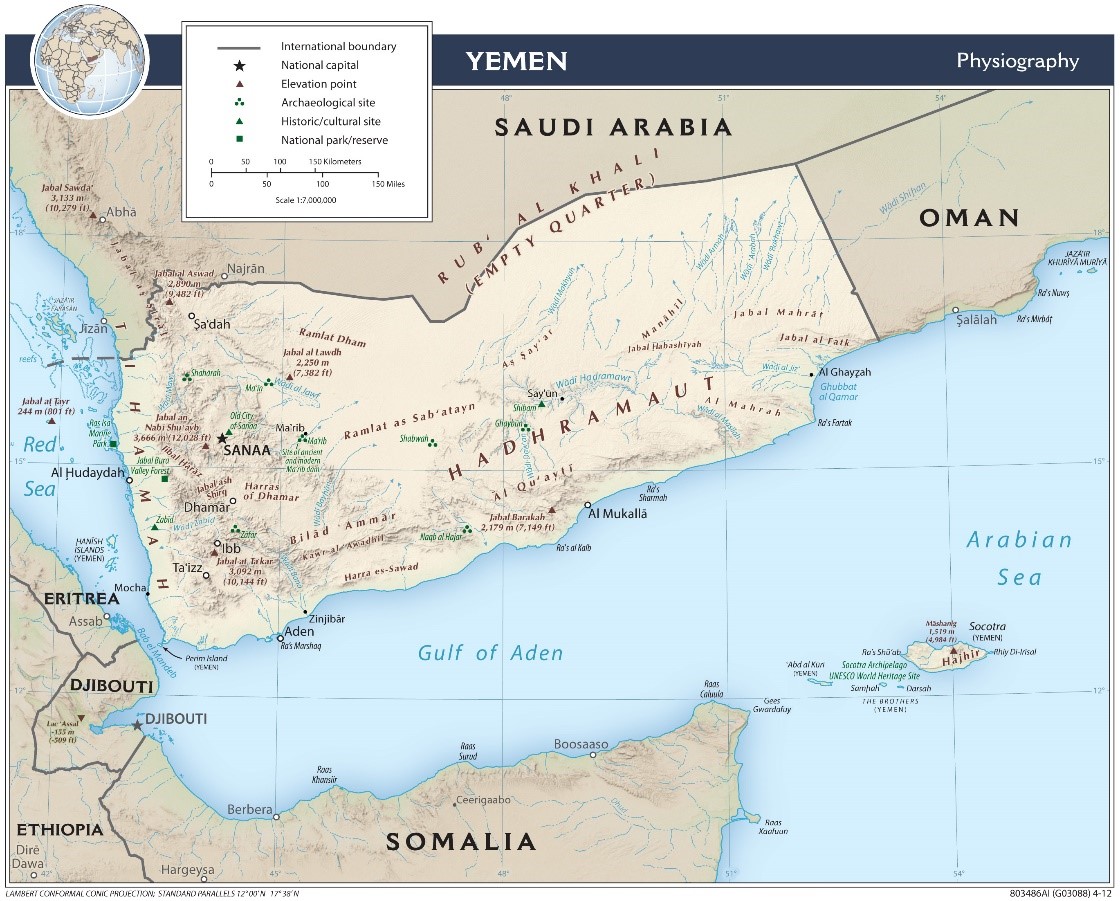

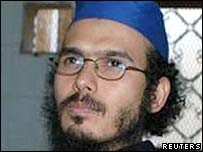

A continuing irritant in Yemen-U.S. relations is the status of Shaykh Abd al-Majid al-Zindani, the country’s most prominent Islamist and leader of the Iman University in Sanaa. In February 2004, the U.S. Treasury Department identified al-Zindani as a “specially designated global terrorist” (Terrorism Monitor, April 6). The U.S. would like to see the Shaykh extradited for his al-Qaeda connections and possible involvement in the USS Cole bombing, but al-Zindani enjoys the personal protection of Yemen’s president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, who describes him as “a moderate.” The president called such extradition attempts “unconstitutional” and noted that “we are not the police of any other country” (Yemen Observer, March 1)

The Shaykh met in early April with Khaled Meshaal, the Syrian-based leader of Hamas. At a fundraising event for the new Palestinian government (which has lost nearly all foreign aid from the West), al-Zindani referred to Hamas as “the jihad-fighting, steadfast, resolute government of Palestine” (UPI, April 14). Al-Zindani is a leading member of Yemen’s Islah Party, an Islamist opposition party that often works closely with the government. The leader of Islah is Shaykh Abdullah al-Ahmar, chief of the powerful Hashed tribe. President Saleh and many other government figures are members of the Hashed. Al-Ahmar is close to the Saudis, and it is partly through his mediation that many long-standing territorial and security disputes have been resolved in the last few years.

Al-Zindani is one of many Yemeni “Afghans,” the term used for veterans of the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan. Rather than alienate the so-called Afghans, Saleh’s regime has used them to eliminate opponents of the government, most notably in the assassination campaign against members of the Yemen Socialist Party in the period 1990-94. Others are reported to have been deployed against Zaidi Shiite militants in Northern Yemen.

Meanwhile, Saudi-born Mohammad Hamdi al-Ahdal is facing the death penalty in another U.S.-related prosecution. A veteran of conflicts in Afghanistan and Chechnya, al-Ahdal is charged with being a leading member of Yemen’s al-Qaeda network, raising funds and organizing bomb attacks on U.S. interests in the country. He has admitted to collecting over one million Saudi riyals to buy the allegiance of Yemeni tribesmen in the Ma’rib region. Nineteen security men were killed in a three-year pursuit of al-Ahdal that ended in 2003. Al-Ahdal used his chance to speak in court to charge Saudi and U.S. authorities with pressing Sanaa for a conviction. Al-Ahdal’s onetime superior in al-Qaeda, Ali Qaed Senyan al-Harthi, was killed in Ma’rib in 2002 by a U.S. unmanned Predator aircraft.

Nineteen men currently on trial in Sanaa are accused of planning attacks against U.S. interests as revenge for the killing of al-Harthi. The suspects, including five Saudis, are accused of operating under the instructions of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, leader of the al-Qaeda faction in Iraq (Yemen Times, April 16). Two of the accused have admitted to possessing arms and explosives for use in training fighters for Iraq and Afghanistan, but proclaimed that their war was with the United States, not Yemen (Yemen Observer, March 4).

In an interesting case that attracted little attention, a group of former Iraqi army officers were acquitted on appeal in March on charges of plotting to attack the U.S. and UK embassies in Sanaa. Other former Iraqi officers are reported to have found employment in Yemen’s military. The two armies cooperated extensively in the Saddam Hussein era, and a large part of Yemen’s military received training in Iraq. The Iraqis have spent three years in prison, but appealed to be allowed to stay in Yemen over fears for their safety in Iraq.

Furthermore, on April 19, a group of 13 Islamists led by Ali Sufyan al-Amari were handed prison terms of up to seven years for plotting attacks against political and security officials in Yemen. Prosecutors announced in late April that 60 more suspected members of al-Qaeda are being brought to trial (26September.com, April 25).

Though the mass prosecutions suggest Yemen is mounting a successful campaign against Islamist militants, hundreds of convicted extremists have found a quick route to freedom through cooperation with Yemen’s Dialogue Committee, which engages the prisoners in a Quran-based rehabilitation program. Other convicted Islamists are released in periodic amnesties, while suspects with political connections are often never brought to trial. Over 800 Zaidi Shiite rebels were freed in March in order to resolve the 2004-2005 conflict that erupted in the mountains of Northern Yemen. While the “revolving door” system of Yemeni justice frustrates U.S. security agencies, dispute resolution, mediation and reconciliation are all traditional art forms in Yemen’s fractious social framework. They are what prevent the state from disintegrating, and Saleh’s proficiency in these skills keeps the regime afloat.

Hunting Fugitives

Yemeni security forces continue the hunt for the 23 Islamists who escaped prison in Sanaa in February 2006. The facility was run by Yemen’s leading intelligence service, the Political Security Organization (PSO). Particularly distressing to the U.S. was that many of the fugitives had been involved in terrorist attacks against U.S. interests, while some were making their second escape from PSO prisons. Eight of the escapees have surrendered or been captured, but the two most prominent fugitives, Jamal al-Badawi and Jaber Elbaneh, remain at large. Al-Badawi was sentenced to death in 2004 for planning the attack on the USS Cole, while Elbaneh was one of the so-called “Lackawanna Six,” a terrorist cell based in upper New York state. Of the six, five are serving sentences in U.S. prisons, but Elbaneh escaped to Yemen where Yemeni police eventually detained him.

Security forces are reportedly using tribal and religious leaders in negotiations with the other fugitives for their surrender (Yemen Observer, April 3). Several PSO prison governors were put before a military tribunal on April 27 on charges of “inadequate conduct” in relation to the escape. The PSO is widely believed to include Islamists in its ranks, and there were serious questions raised at the time of the escape regarding PSO assistance to the escapees.

The escape has created barriers to the release of over 100 Yemeni detainees in Guantanamo Bay. The Yemen government maintains that 95 percent of these prisoners have no involvement in terrorism. According to a government study, most of the captive Yemenis worked in Afghanistan as teachers of the Quran or the Arabic language (26September.com, March 21). Nevertheless, some prisoners already released from Guantanamo Bay have been charged in Yemen with membership in al-Qaeda. One Yemeni prisoner who is unlikely to be released anytime soon is Shaykh Muhammad Ali Hassan al-Muayad, who is serving 75 years in a Colorado prison for financing terrorism. The Shaykh was a member of the Shura Council of the Islah Party and imam of the main mosque in Sanaa before he was arrested in Germany in 2003 and extradited to the U.S. Al-Muayad complains of mistreatment in the U.S. and his family is appealing to President Saleh to intervene.

The escape has created barriers to the release of over 100 Yemeni detainees in Guantanamo Bay. The Yemen government maintains that 95 percent of these prisoners have no involvement in terrorism. According to a government study, most of the captive Yemenis worked in Afghanistan as teachers of the Quran or the Arabic language (26September.com, March 21). Nevertheless, some prisoners already released from Guantanamo Bay have been charged in Yemen with membership in al-Qaeda. One Yemeni prisoner who is unlikely to be released anytime soon is Shaykh Muhammad Ali Hassan al-Muayad, who is serving 75 years in a Colorado prison for financing terrorism. The Shaykh was a member of the Shura Council of the Islah Party and imam of the main mosque in Sanaa before he was arrested in Germany in 2003 and extradited to the U.S. Al-Muayad complains of mistreatment in the U.S. and his family is appealing to President Saleh to intervene.

Yemen and the War in Iraq

U.S. intelligence has identified Yemen as a leading source of foreign fighters in the war in Iraq. The leader of the Islamic Army of Aden-Abyan (one of Yemen’s largest Islamist militant groups), Khalid Abd al-Nabi, has complained that members of his group were arrested by PSO officers and then taken before U.S. operatives for interrogation regarding plans to fight coalition forces in Iraq (Yemen Times, April 4). The Islamic Army was formed in 1994 from “Afghans” who had helped Saleh’s regime defeat Southern Yemen’s socialists. They are accused of maintaining ties with al-Qaeda while sending fighters to join al-Zarqawi’s network in Iraq.

In 2002, the government mounted a largely ineffective assault with heavy artillery and helicopter gunships on the group’s training camp in the mountains near Hatat in Abyan district. Abd al-Nabi surrendered to the government, but was only briefly detained before being released without charges. Convicted Islamist militants released through the Dialogue Committee program agree to avoid further militancy within Yemen, but there is no mention made of Iraq.

Conclusion

A report released in April by Yemen’s Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation revealed that 41 percent of Yemenis are below the poverty line and lack access to basic health and educational services (Yemen Times, April 25). Rising food prices, a 17 percent unemployment rate and a general lack of opportunity for Yemen’s youth provide a pool of dissatisfied recruits for Islamist organizations.

The number of Yemenis currently fighting in Iraq is probably not large, but the presence of the conflict provides an external outlet for Yemen’s most militant Islamists, much like Afghanistan once did. With the Islamist opposition forming the largest political force in Yemen outside of the current government, the United States will continue to find it difficult to leverage the Saleh regime. Any U.S. intervention at this point would present serious consequences for the stability of the region. For now, Yemen will remain a troubling ally in the war on terrorism.

This article first appeared in the May 4, 2006 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor