Andrew McGregor

AIS Special Report, July 9, 2018

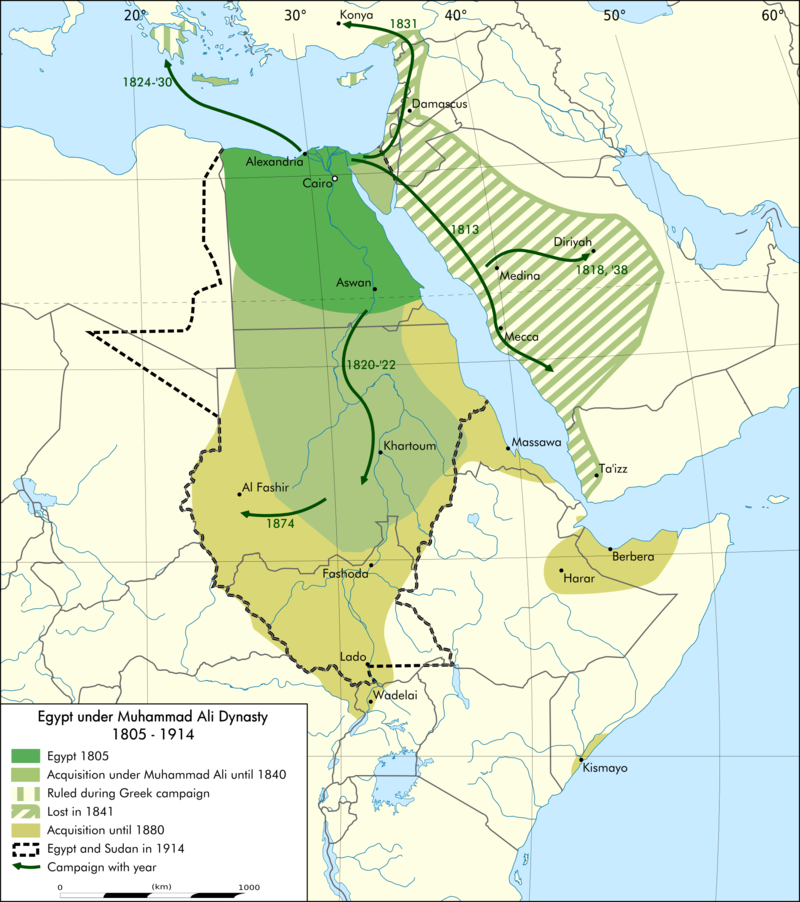

Libya’s fractious southern desert region is dotted by castles dating to Libya’s 19th century Ottoman period and the succeeding era of Italian colonial occupation in the early 20th century. The purpose of these defensive works was always the same: establish a fortified position with a strong garrison at choke-points of the Saharan trade network. Government control of watered oases, food supplies and local trade forced most caravans into communities dominated by fortifications intended to convince local tribes of the permanence of the occupiers. [1]

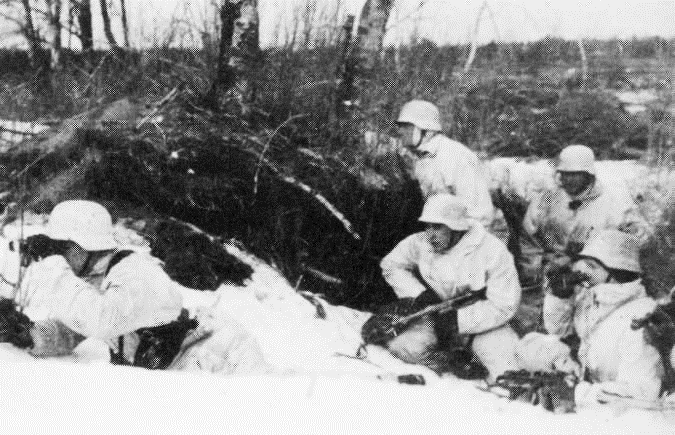

Sabha Castle Under Fire by Tubu Fighters (Libyan Express)

Sabha Castle Under Fire by Tubu Fighters (Libyan Express)

Insecurity in the south has taken the form of sabotage to power and water pumping stations, occupation of oil fields by gunmen, civil conflict, tribal warfare, fuel smuggling, arms proliferation, intrusion of foreign mercenaries, rampant kidnappings, human trafficking and even body-snatching. As fighting rages on around them in bursts of tribal, ethnic or politically motivated violence, Libya’s aging fortresses have become valuable strongpoints in many southern cities, including Sabha, located in the heart of the Libyan Sahara.

The Castle

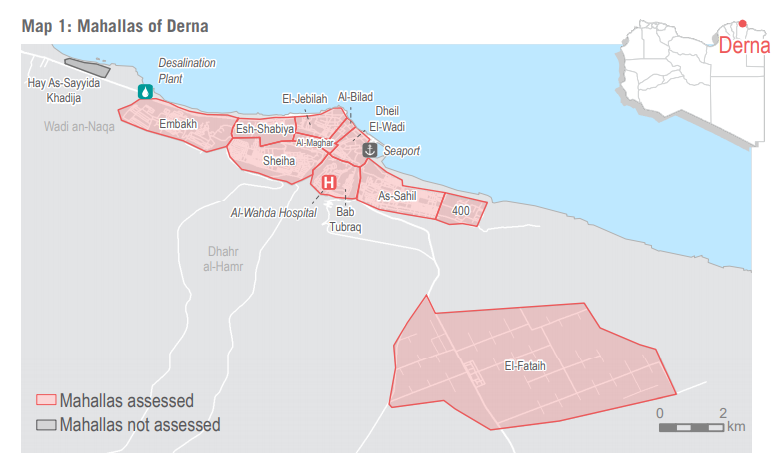

With some 75,000 people, Sabha is the largest city in Libya’s southwestern Fezzan region and is 780 km south of Tripoli. Surrounded by desert, Sabha experiences average daily highs between 88º F and 102º F for seven months of the year. During Libya’s 2011 civil war, the city became a Qaddafist stronghold, only succumbing to revolutionaries aided by British airstrikes in September 2011.

Sabha Market – Castle on horizon, center right.

Sabha Market – Castle on horizon, center right.

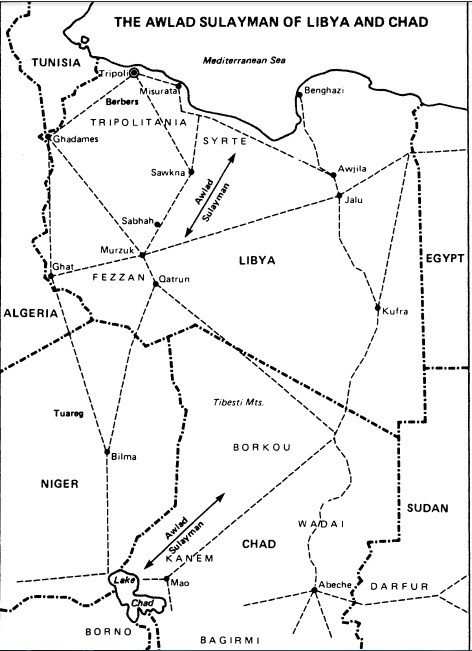

In the chaos that followed the overthrow of Qaddafi, the largely anti-Qaddafi Awlad Sulayman Arabs succeeded in seizing control of Sabha’s security apparatus and created a tribal militia under the official-sounding name of the 6th Infantry Brigade. Various tribal factions turned Sabha into a battleground in 2012 and 2014 as they fought for control of the city and the smuggling routes to the south of it.

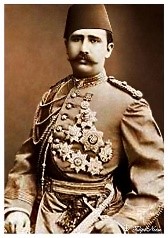

Sabha’s strong-point is undeniably the massive walled Italian colonial-era fortress built atop a hill overlooking the city. Popularly known as the “Sabha castle,” the site is also known as Fort Elena or by its Italian name, Fortezza Margharita. The fortification’s imposing bulk was intended to intimidate the local tribes and consolidate Italian control of Fezzan. In the Qaddafist era, Sabha became a major military base during Qaddafi’s long and ultimately fruitless effort to seize northern Chad. The remote city then became the center of Qaddafi’s equally unsuccessful nuclear weapons program.

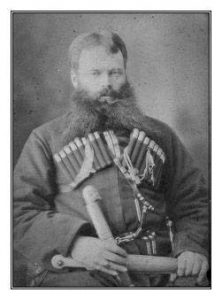

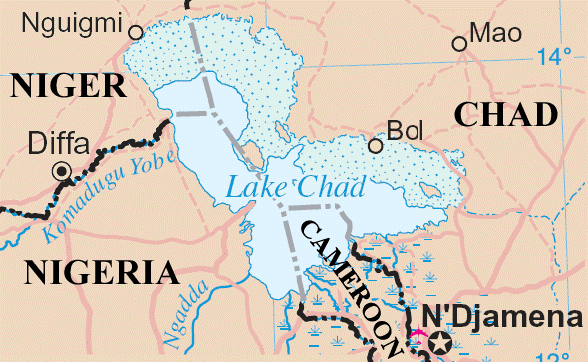

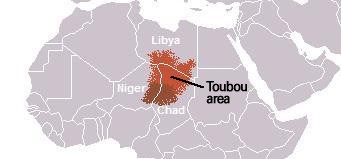

Though it is home to a number of tribes and a significant number of sub-Saharan migrants, two long-antagonistic groups emerged after the 2011 revolution as contenders for control of Sabha, the Arab Awlad Sulayman and the indigenous Tubu, a dark-skinned indigenous people found in parts of southern Libya, northern Chad and northeastern Niger. The Tubu are divided into two broad groups according to dialect; the northern Teda Tubu and the southern Daza Tubu.

The Battle

The struggle between the Tubu and the Awlad Sulayman began to escalate in February with small-scale street clashes. These intensified in early March, as homes, schools and hospitals all endured shelling. With snipers dominating the rooftops, thousands of civilians were forced to seek refuge elsewhere.

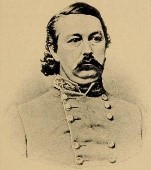

The commander of the 6th Brigade was Ahmad al-Utaybi (Awlad Sulayman). When Haftar prematurely attempted to extend his influence to Sabha by declaring the 6th Brigade a part of the LNA, al-Utaybi instead insisted the 6th was loyal to the Presidency Council/Government of National Accord (PC/GNA) defence ministry in Tripoli rather than the rival House of Representatives (HoR) government in Tobruk (Haftar’s LNA being, at least nominally, the armed wing of the HoR). An angry Haftar ordered al-Utaybi’s replacement by Brigadier Khalifa Abdul Hafiz Khalifa on February 25 (Al-Sharq al-Aswat, February 27). Al-Utaybi’s reluctance to give way led to attacks on 6th Brigade positions in Sabha by LNA-affiliated gunmen, possibly including Chadian and Sudanese mercenaries. Eventually the 6th Brigade was forced to pull back into their headquarters in the castle.

Haftar’s LNA then issued a bold order on March 9, 2017 that they had little chance of enforcing – a voluntary departure of all nationals from neighboring African countries living in the south by March 17, followed by the removal by force of those remaining “using all possible means, both land and air” (Xinhua, March 9, 2018; Middle East Monitor, March 9, 2018). Enforcing this order would likely entail the ethnic cleansing of most of Libya’s indigenous Tubu, many of whom have endured continuing difficulties obtaining citizenship documents after Qaddafi stripped them of their citizenship following the failure of his Chadian adventure. The inability or unwillingness of Libya’s post-revolution leaders to address this issue has contributed to the violence in southern Libya, where the Tubu have come to understand their presence can only be maintained by arms.

The LNA’s “Operation Law Enforcement” began on March 19 after the expiry of the ultimatum for foreign nationals to remove themselves. The operation’s goals were to restore security in the south, extend Haftar’s influence into a strategically vital region and drive those Chadian or Darfuri mercenaries not aligned with the LNA out of Libya.

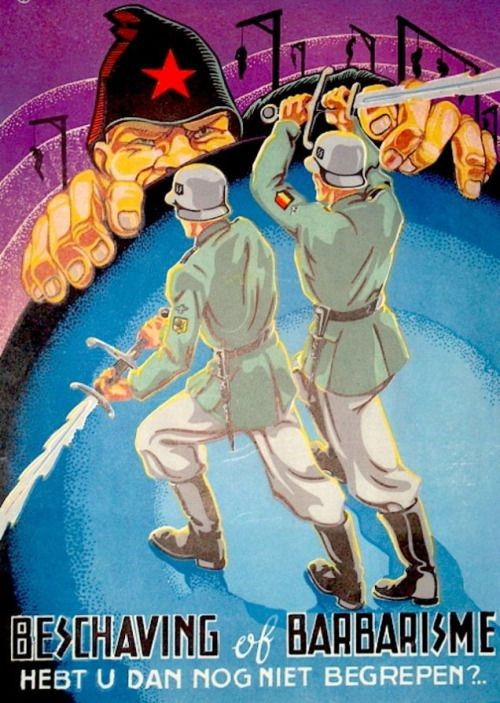

Forbidding Haruj (Norbert Brügge)

Forbidding Haruj (Norbert Brügge)

LNA reports indicated the first airstrike of Operation Law Enforcement targeted a ten-vehicle group of Chadian mercenaries operating out of the Haruj volcanic field of central Libya, a physically hostile region consisting of 150 dormant volcanoes of various sizes and the blackened remains of their lava flows. The region is well known to local nomads, who have visited Haruj since the Neolithic Age seeking volcanic rock for weapons or tools. The wadi-s (dried river beds that funnel seasonal rains) of Haruj continue to offer forage to Arab and Tubu herders to this day as well as temporary shelter for militants.

As part of Operation Law Enforcement, the LNA also despatched units from Benghazi to distant Kufra oasis, 580 miles south into the Cyrenaïcan desert (Libya Herald, March 15, 2018). These arrived in mid-March under the command of Brigadier Belqassim al-Abaj, a former Qaddafi loyalist who held Kufra for Qaddafi until early May 2011, when Tubu revolutionaries and others drove him out. Al-Abaj is a Zuwaya Arab, which is hardly likely to encourage the Tubu, who have struggled with the Zuwaya for control of Kufra since the revolution. Animosity between the two groups dates to the 1840s, when the Zuwaya arrived from the north and made their first efforts to displace the indigenous Tubu. Al-Abaj’s force joined the local LNA-affiliated Subul al-Salam, a Zuwaya Salafist militia that has fought Chadian mercenaries and displaced Darfuri rebels with some success. [2]

On March 18, the LNA reported the arrest of 16 militants who had crossed into Libya near the southern oasis of Kufra from Sudan. The detainees were said to have carried Sudanese and Syrian passports and were veterans of Syrian pro-al-Qaeda movements such as Jabhat al-Nusra (Libyan Express, March 18, 2018; Xinhua, March 18, 2018). The arrests were followed by airstrikes on unspecified targets in southern Libya two days later.

In late March, LNA airstrikes targeted a Chadian rebel group working as mercenaries inside Libya. Though Haftar has employed Chadian mercenaries himself, the targeted group, the Conseil de Commandement Militaire pour le Salut de la République (CCMSR – Military Command Council for the Salvation of the Republic), allied itself with the Benghazi Defense Brigades (BDB), bitter enemies of Haftar. [3] The CCMSR leader, Hassani Bulmay, was arrested in Niger in October 2017.

The Castle Falls

With its new commander finally in place, the 6th Infantry Brigade declared a unilateral ceasefire on April 9, 2018 as well as its allegiance to Khalifa Haftar and the LNA (Libya Herald, April 10, 2018). Mediators and reconciliation experts from the PC/GNA and the rival HoR arrived in Sabha to ease the conflict, but their efforts were generally unsuccessful, largely because of differing approaches and ultimate aims.

By the first week of May, abductions began in Sabha and the deaths of children and other civilians from shelling were reported (Libya Observer, May 7, 2018). The Awlad Sulayman were able to place snipers on the castle’s high points, giving them a clear field of fire into the predominantly Tubu neighborhoods of Tayouri and Nassiriya (Libya Herald, May 14, 2018).

The battle for the castle intensified on May 11-12. The escalation appeared to be due to an attempt by Haftar’s newly-appointed military governor for the south, Major General Mabruk al-Ghazwi, to impose a ceasefire on both parties. Ghazwi had just been transferred from Kufra, where he acted as LNA military commander, and appeared to have lacked a full grasp of the local situation in Sabha. Before accepting a ceasefire, the Tubu demanded to know if their 6th Brigade opponents were now under LNA command. Ghazwi’s response that the brigade was indeed a part of the LNA enraged the Tubu fighters, who determined to drive the Awlad Sulayman gunmen from the castle once and for all.

By May 15, Sabha’s mayor, Hamid al-Khayali, was, describing the situation in Sabha as “tragic” (Libya Observer, May 15, 2018). In response, the Presidential Council (PC) in Tripoli ordered the creation of three new brigades to operate in the south and extend the writ of the PC/GNA (Libya Observer, May 16, 2018; Libya Herald, May 17, 2018).

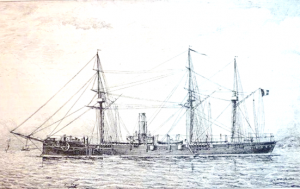

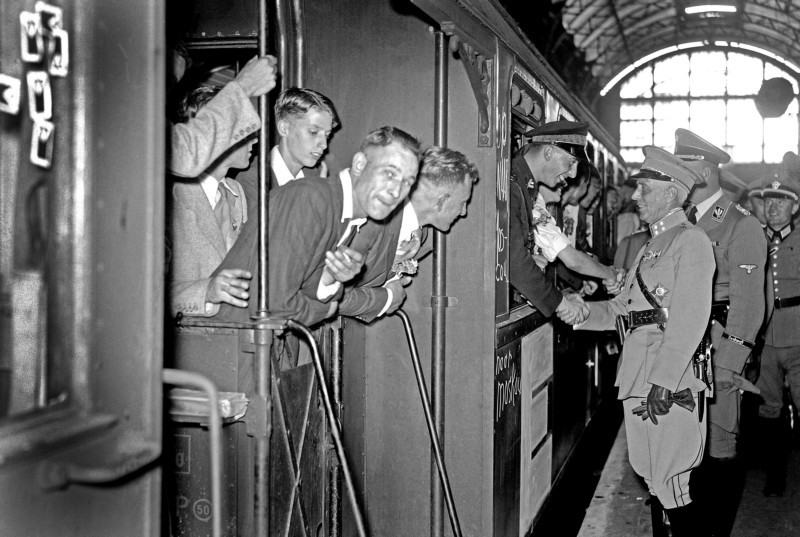

Tubu Range – Daza are in dark red, Teda in light red (Nationalia)

Tubu Range – Daza are in dark red, Teda in light red (Nationalia)

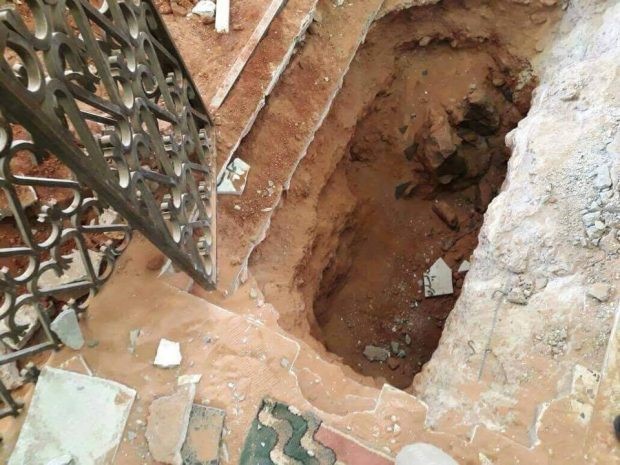

The Tubu, as is customary during clashes with southern Libya’s Arab population, were accused of hiring Tubu mercenaries from Chad and Niger or of being Chadians themselves. The claim is a Qaddafi-era canard that has survived the late dictator, though it must be acknowledged that many Teda Tubu travel back and forth across the unregulated and relatively new border through their traditional lands with some regularity. Awlad Sulayman tribesmen are also found in Chad as a result of flight from Libya during the Ottoman and Italian colonial periods; some of these have returned to Libya since the revolution. During a fierce battle on the morning of May 13, 2018, the Tubu finally broke the defenses of the 6th Brigade and poured into the castle. The Awlad Sulayman brought up armor for a counter-attack, but were ultimately repulsed. The LNA’s military governor al-Mabruk al-Ghazwi then ordered a final withdrawal, leaving the castle and the northern and eastern parts of Sabha in Tubu hands (Libya Herald, May 13, 2018). After taking the castle, a Tubu spokesman invited the Presidential Council (PC) to secure Sabha (Libya Observer, May 13, 2018).

During a fierce battle on the morning of May 13, 2018, the Tubu finally broke the defenses of the 6th Brigade and poured into the castle. The Awlad Sulayman brought up armor for a counter-attack, but were ultimately repulsed. The LNA’s military governor al-Mabruk al-Ghazwi then ordered a final withdrawal, leaving the castle and the northern and eastern parts of Sabha in Tubu hands (Libya Herald, May 13, 2018). After taking the castle, a Tubu spokesman invited the Presidential Council (PC) to secure Sabha (Libya Observer, May 13, 2018).

The castle, which appears on Libya’s 10 dinar bank-note, was badly damaged by artillery, though not for the first time since the 2011 revolution. The latest shelling of the fortress was condemned by the Libyan Antiquities Authority as an attack on “Libyan history and civilization” (Libya Observer, March 5, 2018).

The Struggle for Tamanhint Airbase

Days after the castle fell, fighting broke out at the massive Tamanhint airbase, 30 km northeast of Sabha The base was held by members of the Misratan pro-PC/GNA 13th Brigade (formerly “Third Force”), until May 25, 2017, when LNA forces from southern and eastern Libya began to assemble in large numbers at Traghan (east of Murzuq, 125 km south of Sabha) in late March 2017 (Misrata is a coastal city in northwestern Libya and the home of several powerful anti-Haftar militias). Attacks by these forces and local opposition to the Misratan presence helped convince the 13th Brigade’s leaders to withdraw to the north on May 25, 2017, leaving the base to the LNA.

On March 24, 2018, the base was occupied by the Tarik bin Zayid Brigade, a Salafist militia affiliated with the LNA. The unit is led by Sulayman al-Wahidi al-Si’aiti (aka al-Massloukh, “the skinny one”).

The LNA briefly lost Tamanhint to attackers in 15 vehicles on May 29, 2018, before the attackers were in turn driven off by LNA airstrikes, apparently without loss. The LNA claimed the attackers were a mix of Chadian mercenaries and fighters from the notorious anti-Haftar Benghazi Defense Brigades (BDB) (Libya Herald, May 31, 2018; June 1, 2018). [4]

The Israeli Defense Force in Sabha?

An unconfirmed report from London-based al-Araby al-Jadeed claimed Haftar held an early July meeting in the Jordanian capital of Amman with Israeli intelligence to discuss the insertion of Israeli security forces in Sabha in order to dissuade alleged French and Italian efforts to control the southern region (Middle East Monitor, July 3, 2018). In return, Israel could expect Libyan oil shipments and large orders from Israel’s booming arms industry (presumably despite the porous UN arms embargo).

Other reports suggest that Israeli military assistance to Haftar began in 2014, with the July 2018 meeting being only the latest in a series of secret meetings between Haftar and Mossad representatives in Amman since then. The meetings are allegedly mediated by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which provides substantial military support to Haftar and air support to LNA ground forces (Middle East Eye, August 14, 2017; Reuters, July 25, 2015; New Arab, July 24, 2017). Haftar announced on June 29 that he had information regarding “international forces” seeking to insert military forces into southern Libya in order to bring illegal migration under control. Haftar warned these un-named forces “against such actions, which are considered as a violation of international law and an attack on the Libyan state and its sovereignty” (Asharq al-Awsat, June 30, 2018).

Conclusion

An LNA spokesman in Derna declared on June 11 that the successful conclusion of the two-year battle for that city will be followed by new campaigns to secure southern Libya (Libya Observer, June 11, 2018). Meanwhile, the occupation of Sabha’s commanding fortress by Tubu militiamen has posed a setback to Haftar’s long-range efforts to secure Fezzan through local tribal fighters. Nonetheless, Sabha’s Awlad Sulayman may have suffered a defeat, but the 6th Infantry Brigade remains in the region and will no doubt spearhead any new attempts by the LNA to take hold of the region.

Whether there is any substance to Haftar’s claims that foreign militaries intend to occupy southern Libya to control the flow of sub-Saharan migrants into Europe remains unknown, though both French and Italian troops have established themselves on the Niger side of that nation’s border with Libya’s Fezzan region. With Derna’s last points of resistance likely to collapse by the end of July, the LNA will be able to deploy its forces in the south against those aligned with the internationally recognized PC/GNA government. The resulting chaos may work in the favor of Islamic State fighters already active in Fezzan [5] and attract further international attention, making Sabha’s castle the epicenter of Libya’s ongoing crisis.

NOTES

- Photos of many of these Ottoman/Italian fortifications in Libya can be found at http://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=2837

- For more on Subul al-Salam and their Saudi religious influences, see: “Salafists, Mercenaries and Body Snatchers: The War for Libya’s South,” Terrorism Monitor, April 6, 2018, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4173

- For more on Chadian militant groups operating inside Libya, see: “Rebel or Mercenary? A Profile of Chad’s General Mahamat Mahdi Ali,” Militant Leadership Monitor, September 7, 2017, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4010

- For the BDB, see: “Libya’s Military Wild Card: The Benghazi Defense Brigades and the Massacre at Brak al-Shatti,” Terrorism Monitor, June 2, 2017, http://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3917

- Islamic State militants operate close to Sabha; in March, a US airstrike killed two men alleged to be IS operatives in the southern town of Ubari (Libya Observer, March 24, 2018; Libyan Express, March 24, 2018; NYT March 25, 2018). Ubari is a principal center in the smuggling of weapons, drugs and illegal migrants from the African interior. A statement from US Africa Command (AFRICOM) declared that the attack had been coordinated with the PC/GNA government. It was the southernmost strike in Libya acknowledged so far by AFRICOM (Reuters, March 24, 2018). AFRICOM identified one of the deceased as Musa Abu Dawud, a veteran Algerian militant who led successful attacks against Algerian and Tunisian military posts (AP, March 29, 2018; Arab News, March 28, 2018). The IS leader in Libya is believed to be Al-Mahdi Salam Danqo (aka Abu al-Barakat), who served the Islamic State in Mosul.