Andrew McGregor

Military History Online, August 21, 2016

Romolo Gessi Pasha

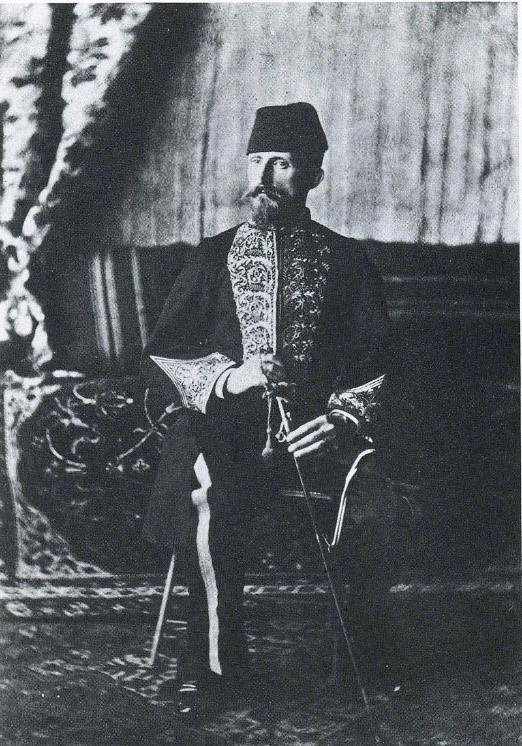

Romolo Gessi Pasha

Successful counterinsurgencies typically combine the deployment of superior weapons, competent logistics, advanced tactics and the ability to win the “hearts and minds” of the non-insurgent population. What is striking about the success of Italian soldier-of-fortune Romolo Gessi Pasha (1831-1881) against insurgent Arab traders and slavers in the south Sudan was his ability to overcome a much larger group of fighters who possessed similar weapons, had greater experience in both irregular and conventional warfare, held fortified positions, were at home in the terrain and had wide public support in the most influential parts of Sudanese society, including the military. Ultimately, Gessi Pasha would go down in history as the relentless weapon used by Sudanese governor-general Charles “Chinese” Gordon to smite the Arab slavers of Bahr al-Ghazal and destroy their expanding influence.

Early Career

Gessi is believed to have attended military schools in Germany and Austria before finding work as an interpreter for British forces in the Crimean War, where he would first meet Captain Charles Gordon of the Royal Engineers, later governor of Sudan’s Equatoria Province (1874-76) and governor general of the Sudan (1877-79).

Dr. Robert W. Felkin, an English medical-missionary and occultist, described the nervous energy that propelled Gessi, “a small wiry man, very impulsive and vivacious. He had grey hair, bright lively eyes and highly nervous hands; he seemed as if he could not sit still for a moment, but was always on the move, and continually occupied in making cigarettes… I think I never met a more entertaining companion.” [1] Gordon later described Gessi in his journal in 1881, when Gessi was 49-years-old: “Short, compact figure; cool, most determined man. Born genius for practical ingenuity in mechanics. Ought to have been born in 1560, not 1832. Same disposition as Francis Drake.” [2] Gessi’s colleague and sometime antagonist Carl Christian Giegler Pasha, the German deputy governor-general of the Sudan until 1883, remarked after Gessi’s death that he had been “one of the most striking figures in the Sudan.” [3] According to Giegler:

When [Gordon] went to the Sudan, he took Gessi with him, for he had a fancy for daredevils like Gessi… He knew how to tame such people and make them useful… Anyone was good enough for the wilds of Central Africa. It was of no importance to Gordon whether the people had previously been honest citizens or rogues. [4]

Giegler claimed Gordon once told him that “Gessi was a fellow capable of the worst and basest actions. Gordon once said to me in the course of conversation, ’Do you know Gessi yet? If I were to order him to kill his own mother, he would certainly do it.’” [5]

When Gessi accepted Gordon’s offer of a staff position in the Sudan in 1873 he was 42-years-old. Though the multilingual Gessi had only an acquaintance with Sudanese Arabic, he did speak Turkish, the command language of the Egyptian Army. While he was now under the authority of the Muslim Egyptian Khedive (Turkish – “viceroy”) and thus an official of the Ottoman Sultan, Gessi had a very low opinion of Islam, which he characterized as only “the first step from fetishism.” [6] Gessi once recommended “colonization on a large scale” to Christianize the Sudan, citing as a model the Protestant Dutch Boers in South Africa. [7]

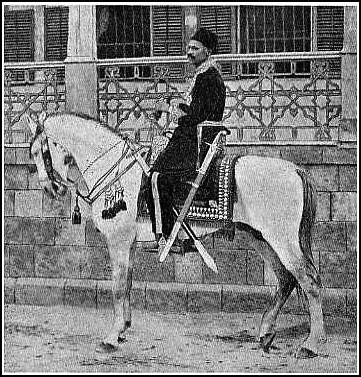

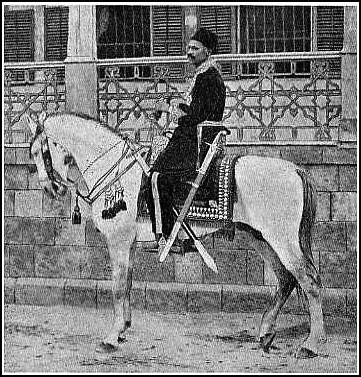

Carl Christian Giegler Pasha

Carl Christian Giegler Pasha

In 1875 Gessi led a mission to Uganda’s Lake Albert conducted on a lice-ridden open boat through continual storms; bananas were often their only food. Gessi feuded with an Italian compatriot on the expedition, beat his Arab sailors with a cudgel and made no useful contacts with the natives. [8] Gessi claimed to have circumnavigated the lake, but according to Giegler, no one in Khartoum believed him. [9] Gessi was often consumed with sketchy money-making enterprises; Giegler and another official lost a substantial sum of money in Gessi’s attempt to speculate in sorghum, an incident that may have helped color much of Giegler’s later negative assessments of Gessi’s character. [10]

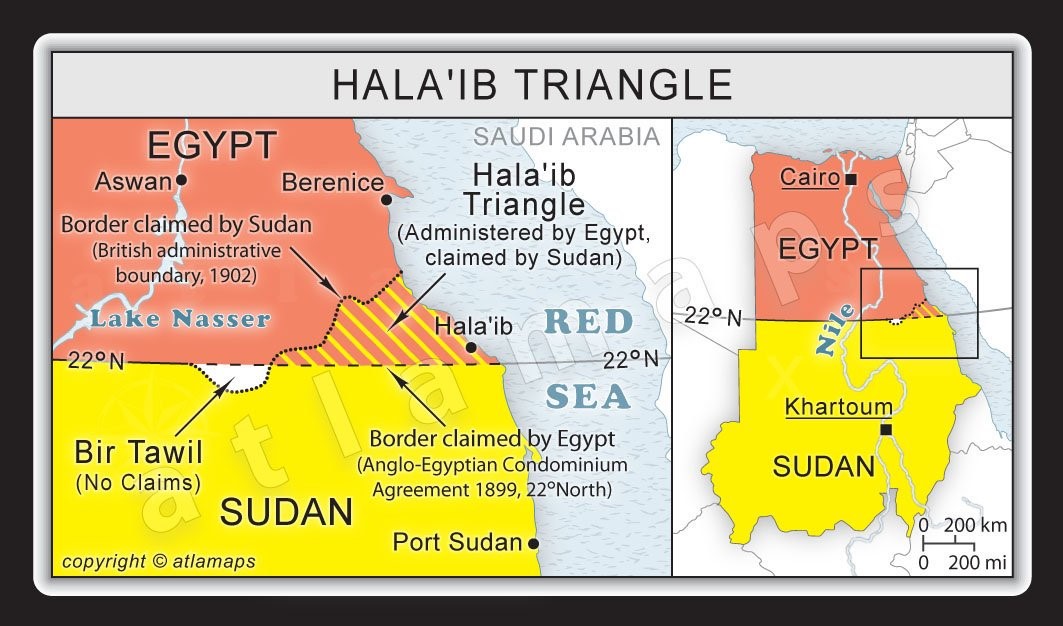

Gessi resigned after Gordon presented him with only a minor Ottoman decoration for his work on Lake Albert. [11] An 1878 mission to the Upper Sobat region followed and Gessi was planning yet another venture in the southern Sudan when news came that Sulayman Bey Zubayr had revolted in Bahr al-Ghazal Province, massacring the Dem Idris garrison and 400 loyal Arab traders before proclaiming the independence of Bahr al-Ghazal. Despite Gessi’s resignation, Gordon asked him to mount an expedition against the powerful rebels.

Bahr al-Ghazal in the Age of Slavery

After its conquest by Egypt in 1821, Sudan was ruled by elements of the non-Arab Turco-Circassian elite that dominated Egypt’s Arab majority. Though the Egyptian Khedive ruled largely independently of his nominal master, the Ottoman Sultan, the Egyptian administration in Sudan was dominated by Turks, Circassians and other peoples of the far-flung Ottoman Empire. Of local importance were the three powerful Arab tribes of northern Sudan, the Danagla, the Ja’aliyin and the Sha’iqiya.

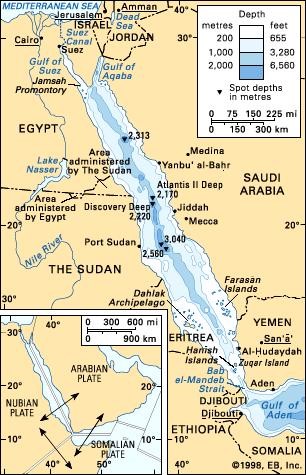

In the mid-19th century so much of Sudan’s economy was built around slave labor that any attempt to simply abolish it would mean the ruin of the country and certain revolt. From 1837 to 1848, the Egyptian government maintained a monopoly on the south Sudan slave trade. This trade was eventually turned over to private merchants before Cairo yielded to international pressure in 1869 and engaged Sir Samuel Baker to abolish slavery in Egypt’s southern dominions. Baker’s often brutal methods succeeded mostly in displacing the slave trade from Sudan’s Equatoria Province to the less accessible Bahr al-Ghazal Province.

Prior to 1850, trade in the Bahr al-Ghazal was largely carried out by itinerant Arab and Arabized-Nubian traders from north Sudan known as jallaba. However, as ivory began to dry up, the traders turned to “black ivory” – slaves. Up to this point, the jallaba (not all of whom were slavers) had paid local rulers for trading rights and protection, but now aligned themselves with the armed trading establishments run by Khartoum-based trading houses.

Europeans and Levantines were also important as ivory traders in Bahr al-Ghazal, but most had sold their interests to Arabs by 1862 as a result of the depletion of ivory stocks, the undesirability of being associated with the expanding slave trade and the increasing violence in the region. [12] The slave markets in Khartoum were closed in 1857 but reopened in more inaccessible places in the south. Nonetheless, the European traders based in Khartoum continued to profit from the trade by offering high-interest loans to Arab slavers. [13]

In 1877 the Egyptian Khedive signed an anti-slavery agreement with the British government that called for an immediate end to the slave-trade and the gradual elimination of slavery over seven years in Egypt and twelve years (i.e. 1889) in the more slave-dependent Sudan. Gordon maintained that the agreement could never be properly implemented in that time-frame: “No man in the place of a governor would plunge the whole country into revolt on this question…” [14]

Most slaves were women who performed domestic tasks or were destined for harems in Cairo, Istanbul and other parts of the Ottoman Empire. Corvée labor was usually preferred to slave labor on large projects and plantation labor was rarely performed by male slaves, who were instead diverted to the army for training before being sent back to the Sudan as soldiers. Manumission, susceptibility to disease (particularly Cairo’s regular plague epidemics) and low fertility rates meant that the slave population was constantly in need of replenishment.

Most of the leading traders in Sudan established zariba-s, trading settlements initially fortified by encirclements of thorn bushes and later by earth berms and timber. The traders deployed thousands of armed men, many of them bazinqir-s, former slaves who were allowed a share of the profits in return for their service. Maintaining private armies was not cheap, however, and the traders increasingly focused on expanding the slave trade with the connivance of officials of the Turco-Egyptian government. Unable to assert its authority in the region, the government attempted to integrate the traders into the official administration, giving their activities a degree of immunity.

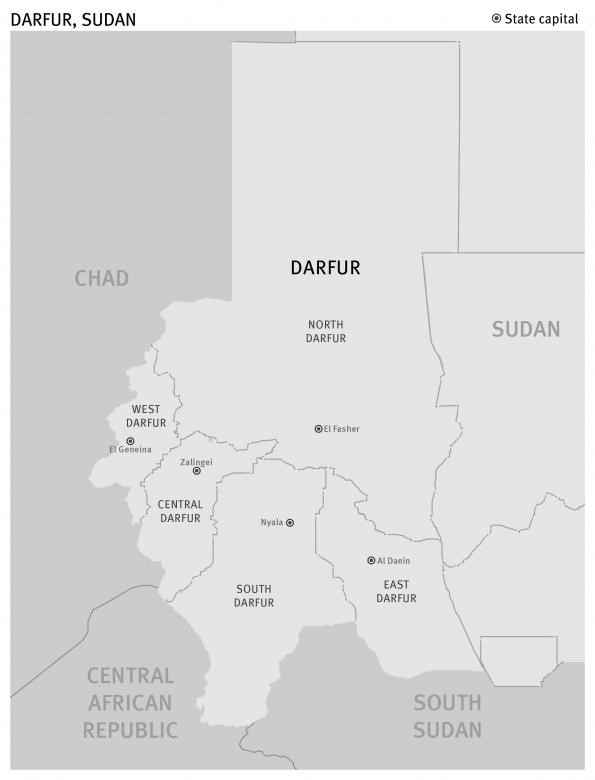

With the main occupation of Egyptian Army detachments in the region being the collection of slaves and ivory, the traders began sending their illicit cargoes north through desert routes to avoid the Nile. Mortality rates were now far higher, making it necessary to send greater numbers of slaves north in order to maintain the normal profit margins. Sulayman’s powerful father, Zubayr Rahma Mansur Pasha (c. 1831 – 1913), attempted several times to negotiate right-of-passage treaties with the Baqqara (cattle-raising) Arabs of southern Darfur, but despite agreeing to a pact in 1866, the Arab tribesmen could not in the end be persuaded that receiving payment for passage would ultimately be more profitable than raiding slave caravans. These difficulties eventually inspired Zubayr to invade Darfur and add it to his personal empire.

The slavers’ private armies were no mere rabble; in most cases they were as disciplined as government troops, often better fed and supplied, at least as well armed and frequently more experienced in combat and the use of firearms. The men were fiercely loyal to their commanders and were paid in goods, including cattle and slaves. [15]

Zubayr Pasha and Sulayman Bey

By 1865, Zubayr controlled most of the Dar Fertit region of Bahr al-Ghazal. Following a successful thirteen-month war with the militarily powerful Zande peoples, Zubayr found himself the strongest force in the region by early 1873. In the meantime, Zubayr had angered authorities in Khartoum in May 1873 by killing the government-appointed ruler of Dar Fertit, an adventurer from Baguirmi (a slave-raiding sultanate in southern Chad) who had tried to seize Zubayr’s goods on a pretext.

Zubayr Pasha

Zubayr Pasha

In December 1873 the Khedive issued a royal decree making Zubayr governor of Bahr al-Ghazal with the Ottoman rank of Bey (a high Ottoman administrative rank, second to Pasha). [16] With his status vis-à-vis the government now normalized, Zubayr began to use his ever-increasing wealth to bribe all levels of officialdom, making himself one of the most powerful men in Sudan.

After a series of disputes with the Khedive’s appointee as Darfur governor, Zubayr decided to travel to Cairo in 1875 to lay his case before the Khedive personally, leaving a force of 6,000 men under the command of his son Sulayman (Zubayr maintained Sulayman was 15-years-old at the time; Gordon believed he was 21, a more likely age). [17] Though he was initially received with great ceremony, Zubayr eventually learned that the Khedive intended his stay in Cairo to be permanent to sideline the possibility that Zubayr might create a mighty empire in Darfur that could eventually threaten Egypt. [18]

While in Cairo, Zubayr met with Gordon, who was on his way back to the Sudan. Zubayr entrusted his son’s safety to Gordon while writing to Sulayman to remain loyal. Shortly after Gordon’s arrival in Khartoum he succeeded in quelling a revolt by Sulayman, but rather than executing the young man, Gordon exacted a promise of future loyalty and released the would-be rebel. The governor-general’s decision to free Sulayman was calculated rather than based on moral softness; Gordon expected reciprocity when he was magnanimous and, in this sense, Sulayman’s days were numbered once he decided to launch a new revolt. [19]

An unconfirmed story claims Zubayr had gathered his officers under a Tamarind tree near Shakka (a town in south Darfur Zubayr had seized from the Baqqara Arabs) and instructed them to revolt if they received a message from Cairo to “carry out the orders given under the tree.” Gordon believed such instructions were sent after he refused to assist Zubayr’s return from Cairo. [20]

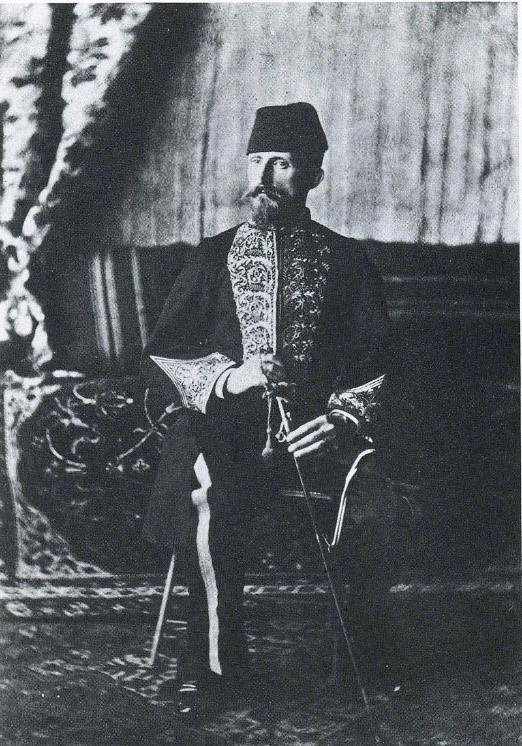

Charles George Gordon Pasha in Ottoman Uniform

Charles George Gordon Pasha in Ottoman Uniform

Meanwhile, Zubayr’s empire had been damaged by the maladministration of Idris Abtar, a Danagla slave-trader and merchant who had been appointed in Zubayr’s absence. Rightfully sensing trouble with Sulayman and his Ja’aliyin following, Idris convinced Gordon that Sulayman was in revolt. Idris was given command of Bahr al-Ghazal and set out with some 200 regulars to bring Sulayman to heel. Sulayman reportedly wrote to Gordon, expressing his willingness to submit to a Turk or European, but not to Idris, whom he regarded as a mere servant of his father. [21] Sulayman now seized Dem Idris and slaughtered the garrison, which brought support from other leading slave-traders opposed to the government’s anti-slavery measures. However, as Gessi noted, “Gordon Pasha was not the man to leave acts of revolt and the massacre of his soldiers unpunished.” [22]

Sulayman’s Revolt

Prior to Sulayman’s revolt, Bahr al-Ghazal, a massive province of over 48,000 square miles at the time, was held for the Egyptian government by only two companies of Egyptian Army regulars, 2 cannon and 700 irregulars, the latter including Arab Sha’iqiya horsemen, local slave-troops and a mixed bag of adventurers and bashi-bazouq (“cracked brains”), Ottoman mercenaries who worked mainly for loot. Sulayman, on the other hand, had four “superior” cannon (with ample supplies of shells and grapeshot), Congreve rockets, ammunition in “enormous quantities” and thousands of well-trained troops. [23]

If Gessi was unaware of the hopelessness of his task, there were many in Khartoum who were ready to remind him: “When, solicited by Gordon, I accepted my mission, everybody began to laugh, saying that Gordon wished at all costs to get rid of me, and that he was sending me to certain death.” [24]

Sulayman’s appeals for fighters brought in thousands of recruits eager to preserve their slice of the lucrative slave trade. According to Gessi, Sulayman had some 700 wives, concubines and slaves, his lieutenant Rabih Fadlallah had 400 slaves, individual Arabs typically had 50 to 100 slaves, and even the lowly bazinqir-s could expect to own five to ten slaves each.

Many of Gessi’s troops were former slaves purchased by Gordon, a recruitment method that earned Gordon the ire of the politically influential London-based Anti-Slavery Society. Gordon did not have great confidence in the rough types of dubious loyalty of the Egyptian Army in the Sudan commanded by Gessi, noting in his diary that: “I am very anxious about him, amid all that gang of scoundrels.” [25]

Though a loyal servant of the Khedive, Gordon was at all times aware of the corruption and brutality that characterized the Turco-Egyptian administration of the Sudan, suggesting that had Zubayr’s group not been slave-traders it might have been better for the people if the revolt had been successful. [26]

In Pursuit of the Slavers

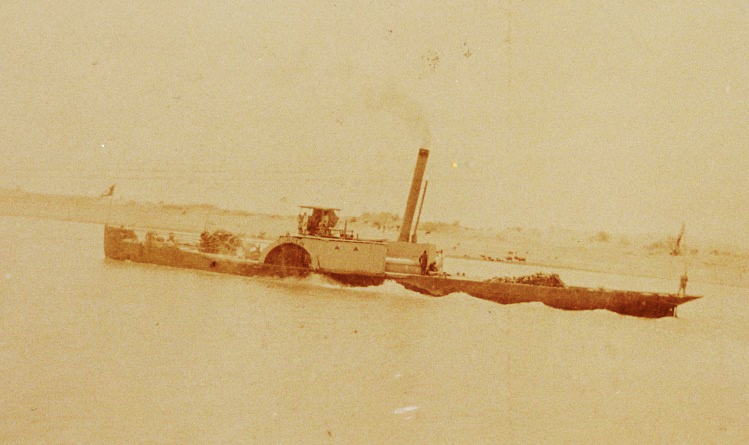

Gessi left Khartoum on July 15, 1878 on the steamship Burdayn with 40 soldiers before spectators entranced by the sight of men heading to a certain death. [27] The strategic goal was to prevent Sulayman’s forces from joining in the north with the 5,000 men under Amir Muhammad Harun al-Rashid, a Fur prince who was seeking the expulsion of Egyptian troops from Darfur and the re-establishment of an independent Fur sultanate. [28] Gessi believed that Sulayman was intent on using Darfur as a base to seize Khartoum and force the Khedive to free his father.

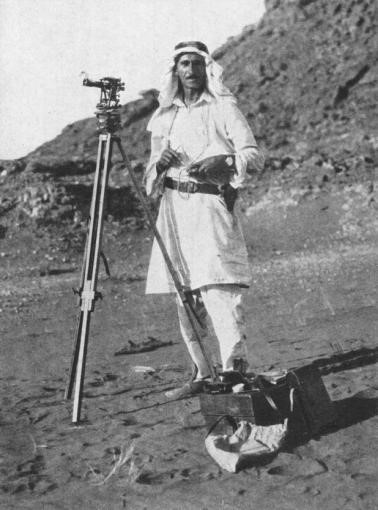

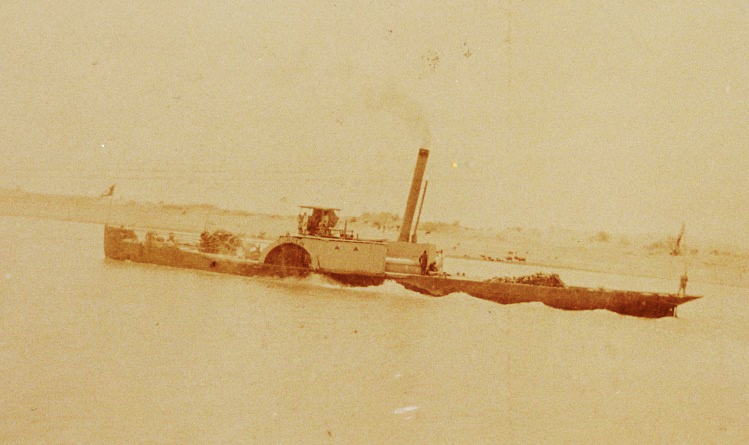

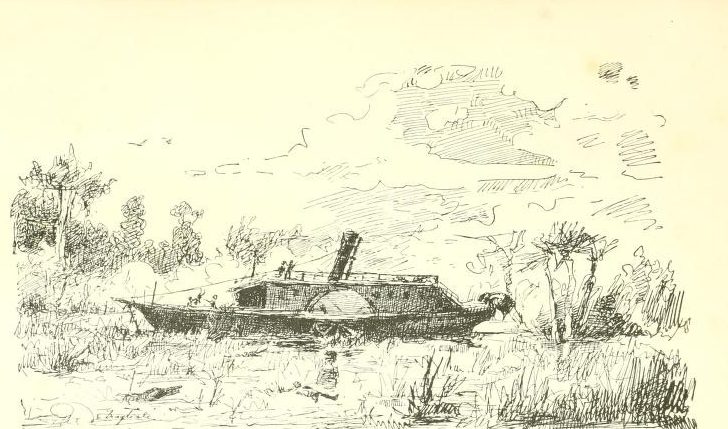

The Burdayn on the Nile

The Burdayn on the Nile

The difficulty faced in eliminating the deeply entrenched slave trade was apparent when Gessi detained a two-masted dahabiya (a shallow-bottomed boat designed for use on the Nile) carrying 92 slaves crammed below decks. The ship was government-owned, the slaves were in the care of an officer of the regular army, and the cargo allegedly belonged to Colonel Ibrahim Fawzi Bey, governor of Equatoria Province and a favorite of Gordon. The captain of the ship was the brother-in-law of Yusuf Bey al-Shallali, Gessi’s Nubian second-in-command. [29]

Gessi expected to collect more troops on the way, but when he reached the garrison at Fashoda, he found only sick and convalescent men, of whom “the greater part were afflicted with syphilitic diseases, festering wounds, and the itch.” [30] The Fashoda arsenal was empty; at Lado, officials made 240 antique firearms available, but hid from Gessi all the modern Remingtons and ammunition.

By October 1878, Gessi could only muster 3,000 of the 7,500 troops he expected to command. At Rumbek, he obtained four companies of regulars and 1,000 irregulars of questionable loyalty, most having friends and relatives in the rebel camp. Arabs enticed many of the men to desert, a practice Gessi inhibited by publicly executing a deserter and flogging others.

The annual floods in the region that inhibited campaigning began to fall, and by mid-November 1878, Gessi was ready to march against the rebels. Once the fighting had started, Sulayman received a telegram from his father urging submission, an approach also favored by a council of 12 elders established to advise the young Sulayman. This advice was dismissed, with Sulayman convinced that he and all the leading men under him would be executed if they surrendered. [31] Nonetheless, Sulayman consented to sending two delegations to Gordon; all members were executed by Gordon as spies on Gessi’s advice. [32] This marked the end of any possibility of a negotiated settlement. Success would now be the only means of survival.

From the beginning, Gessi’s advance overland was slowed by thick vegetation and the soldiers’ insistence on bringing their women, children and slaves with them, a practice Gessi knew would hamper his progress but felt unable to correct without provoking dissent in the ranks. [33] The camp followers left the columns in a “perpetual turmoil which at times threatened a hopeless confusion.” [34]

Terrain was near impassable at times; one particular five-hour “march” through waist-high swamp water underlain by thick, boot-sucking mud was called “the Devil’s Walk” by Gessi’s men. Forty-two men declined to answer the roll-call that night, “lying in the mud, preferring to die rather than go on, as they had no more strength.” [35] Powerful lightning storms lit up the nights and rain fell “with such force that it took one’s breath away.” [36] Villages on the way had been emptied by the slavers, who also burned grain-stores and the boats needed to cross crocodile-infested rivers.

Fatal illnesses such as smallpox and dysentery struck with frequency, while Gessi complained it was difficult to convince fatalistic Muslims of the wisdom of preventative health and sanitation measures. Lack of medical treatment meant an agonizing death was the most common fate of the wounded on both sides. The methods of the few Egyptian doctors under Gessi’s command was eye-opening: “Never have I seen doctors beat sick soldiers!” [37]

Constant ammunition shortages were another problem. Sulayman’s Arabs made their own copper bullets with metal from southern Darfur and traded slaves for ammunition and food. At times, Gessi had to order his troops to gather spent rebel bullets to be recast into ammunition for government rifles, sometimes in the midst of a firefight. When ammunition did arrive, it was in the form of ingots of lead and barrels of powder. Paper for making cartridges was in short supply, with official stationary and books from Gessi’s baggage being pressed into use during one crisis.

When supplies of meat and salt expired, Gessi noted that Zande troops under his command remained healthy, “owing to the feeding on human flesh. Directly after a battle they cut off the feet of the dead as the most exquisite dainties, opened the skulls and preserved the brains in pots.” [38] What is implicit here is that Gessi, like the later Congo Free State army of the 1890s, tolerated such practices, preferring to reserve the use of authority for measures directly concerned with military success while enjoying the psychological threat cannibalism imposed on the enemy.

By December 12, Gessi had gathered 2400 soldiers under his command at Wau, thanks in part to the decision of trader Abu Amuri to join the government side, bringing with him 700 armed men. [39] This force enabled Gessi to advance on Dem Idris, which under Sulayman had been commanded by ‘Abd al-Qassim, “a wild beast in human form” alleged to have conducted human sacrifices. [40]

If he tried to assault Dem Idris directly, Gessi was guaranteed a ferocious fight from a defending force at least as large as his own when assaults on fortified positions usually dictated a minimum of a three-to-one advantage over the defenders. Gessi dictated a message to a captured spy warning of the imminent arrival of large numbers of government troops at Dem Idris. The letter, written in the spy’s own hand to guarantee its acceptance, was entrusted to a slave to deliver to Dem Idris. By dawn the next morning, the Dem Idris garrison was falling back on Dem Sulayman, leaving Gessi in control of the fortified position without firing a shot. [41] When the deception was discovered, Sulayman hurled wave after wave of fighters against Dem Idris, whose fortifications had been quickly improved at Gessi’s order. A thousand rebels fell in the 3 ½ hours of continuous assaults against the government troops, most of whom were facing gunfire rather than spears and arrows for the first time. Gessi was astonished by the determination of the rebel fighters: “The best European soldiers could not have shown a greater contempt of death.”

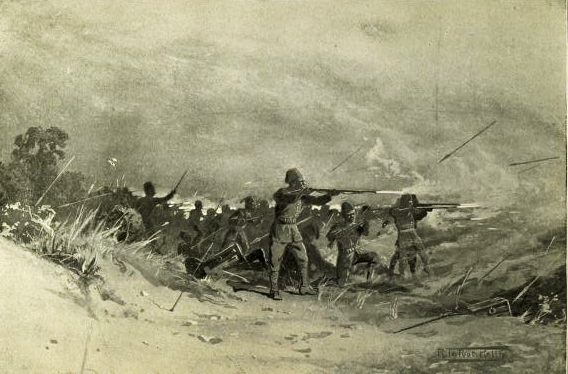

In late December, 1878, Sulayman again turned his forces against Dem Idris, so confident of victory that some of his 10,000 men had been issued with ropes to tie their captives. The Arabs and bazinqir-s stormed the zariba four times before being driven off with the loss of another thousand men. [42]

After receiving reinforcements, Sulayman determined to put an end to Gessi on January 12, 1879, swearing on the Quran with his officers to succeed or die. The rebels made two fierce assaults on Gessi’s defenses, with the Arabs driving the attack forward by decapitating black troops who faltered. The rebels returned to the attack the next day, but Gessi’s outnumbered troops managed to repel the rebels after an exhausting seven hour battle. Sulayman’s force returned to the attack twice more and his artillery set fire to the government camp, but Gessi advanced into the open and defeated the rebels in a further three-hour battle.

By March 1879, food was running short in the rebel camp and Sulayman had begun executing both Arabs and bazinqir-s who expressed dissent. [43] On March 16, Gessi launched four columns against the rebel camp after receiving a much-needed supply of powder and lead. Gessi’s guns and Congreve rockets (still useful, but already a military antique in Europe) set fire to the camp and its tree trunk barricades. Five rebel sorties were driven back, with Sulayman and the surviving rebels forced to abandon the blazing zariba: “The dead lay one upon the other, most of them reduced to a cinder… Our nostrils were offended by the odor of burning flesh, which flamed as if it were fat.” [44]

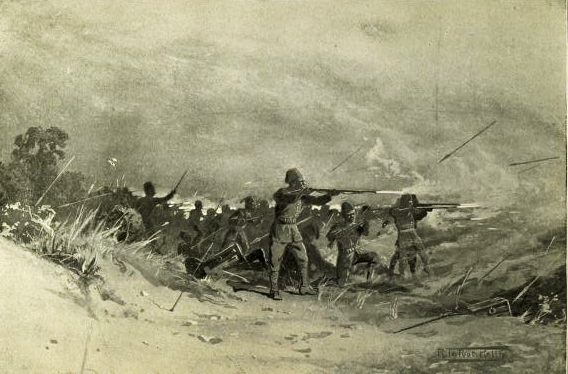

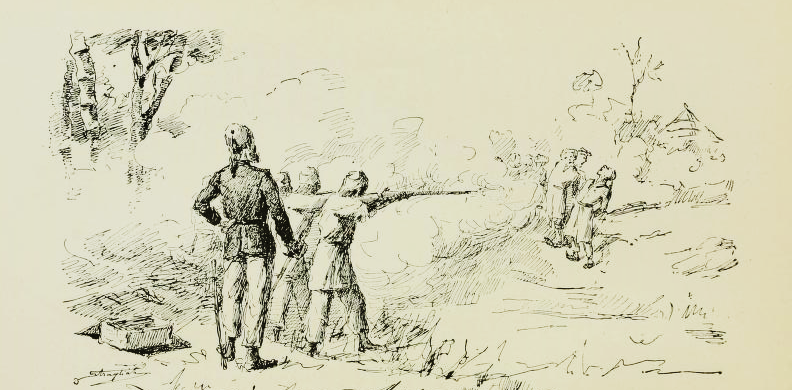

Egyptian Troops Attack Dem Sulayman

Egyptian Troops Attack Dem Sulayman

By now, Sulayman had only 1,000 soldiers left while Gessi had begun striking those zariba-s that served as the prime rebel recruitment centers. After ordering local shaykh-s to kill any jallaba they could catch, Gessi’s native allies began arriving with numerous baskets of heads. [45] Unfortunately, this had the effect of driving the remaining unaligned jallaba into Sulayman’s camp for safety. With the addition of a column of Arab and Zande reinforcements (the Zande were present on both sides), Sulayman was now able to muster over 3,000 men. [46] Though troubled by an outbreak of smallpox and the question of how to feed some 12,000 camp followers, Gessi had received reinforcements and supplies of ammunition. Mass public hangings of captured slavers continued to rouse local support. [47]

After four and a half months at Dem Idris, Gessi’s small army left on May 1, 1879 to take the rebel headquarters at Dem Sulayman. Gessi’s troops defeated a group of rebels outside the camp before storming it on May 4. Sulayman and the rebels fled but pursuit was halted because Gessi’s troops were busy looting Dem Sulayman’s considerable wealth. Gessi later claimed to have found a letter there from Zubayr to Sulayman instructing his son to “free Bahr al-Ghazal from the Egyptian troops…” [48]

Slaver Killing an Exhausted Slave

Slaver Killing an Exhausted Slave

Gessi was now pursuing Sulayman’s forces through uncharted territory as they tried to make for Darfur. Sulayman’s progress was marked by wounded bazinqir-s whose throats had been cut. When Gessi’s advance encountered the bodies of small slave children slaughtered by the traders because of their inability to keep up due to fatigue and hunger, his sorrow “soon gave way to indignation” and some thirty captured slavers were brought up to witness the sight before their execution; according to Gessi, “God punished them by my hand.” [49]

Sensing the time had come to destroy the rebels, Gessi, now made a general by Gordon, assembled a group of chosen men consisting of two companies of regulars and 400 bazinqir-s. The force was small, but von Clausewitz’s maxim was to hold true: “The weaker the forces that are at the disposal of the supreme commander, the more appealing the use of cunning becomes.” [50] Departing on May 9, Gessi’s talent for deception soon brought results.

Gessi avoided the usual roads as he closed in on Sulayman’s chief lieutenant, Rabih Fadlallah. While camped in a glade, several men approached Gessi’s camp shortly after midnight. Mistaking the camp for Rabih’s in the darkness, the men revealed they were an advance party from a group led by Idris al-Sultan, a leading slaver and ally of Sulayman. Staying out of sight, Gessi ordered his men to tell the advance party that they would wait for Idris further on the next day. In the early morning Gessi fell upon Rabih’s camp, killing many, though Rabih himself escaped. The area was cleared of all signs of a battle and Rabih’s flag was re-hoisted beside his tent. Encouraged by some of Gessi’s men posing as Rabih’s followers, Idris al-Sultan’s group was led into a massive ambush outside Rabih’s former camp that began just as a storm broke. Confused and disoriented, most of al-Sultan’s group was annihilated despite repeated attempts to break out. Gessi “felt sorry for these soldiers, but though I admired their pluck I was obliged to order the firing to be continued against those who obstinately refused to surrender.” [51] With food short, Gessi’s men now returned to Dem Sulayman with vast stores of seized ivory and many leading slavers in chains. [52]

Despite promises of great riches and future victories, the shattered morale of Sulayman’s men soon led to acts of insubordination and a rise in desertions. [53] Sulayman had roughly 20,000 people with him at the time, all of them hungry. Native tribes-people removed all the grain in the path of the column, forcing the rebels to subsist on leaves and roots. Hundreds died from hunger daily and those jallaba who fell out encountered the lances of vengeful tribesmen. [54]

The campaign slowed for several weeks as Gessi fell ill and devoted most of his time to sending in great amounts of captured ivory. Gordon, who had occupied Shakka to the north to stop reinforcements from reaching Sulayman, was able to meet with Gessi on June 25. The governor-general remarked that Gessi was “looking much older,” [55] but was able to give Gessi the news of his elevation to pasha, the award of a major Ottoman decoration and a cash bonus of £E 2000.

Constant shortages meant that Gessi was usually in greater need of supplies than men. Even when desperately under strength, Gessi chose not to take untrustworthy irregulars: “The irregular soldiers… were the scum of all that is bad. The greater part, escaping the justice of the Soudan Government, committed the vilest actions; every day they were intoxicated, ravished the native women and carried away everything that fell into their hands.” [56]

The campaign’s pace picked up in early July when a deserter informed Gessi that Sulayman was encamped at three days’ distance. Gessi hastened to catch the rebel, but Sulayman’s spies informed their leader and his force departed in three columns led by Sulayman, ‘Abd al-Qassim and Rabih to join Harun Rashid’s rebels in Darfur. To prevent this rendezvous Gessi led 290 men through rain and mud in three days of forced marches. Meanwhile, Sulayman was having his own problems, with his right-hand man Rabih arguing against the advance into Darfur (Rabih was proved right – Harun Rashid’s rebellion was crushed in March 1880).

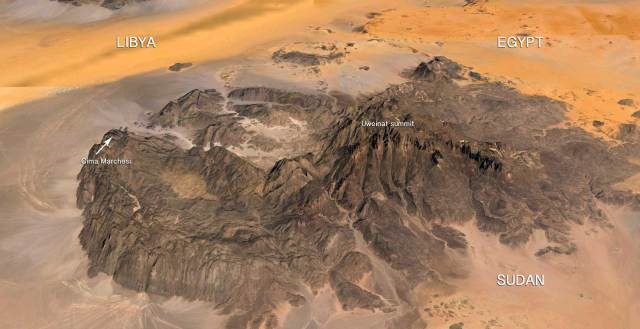

As Gessi’s column neared Darfur, the terrain began to change. This region was dry and often waterless. Massive and isolated Baobab trees replaced the forest and the tracks of elephants, giraffes, gazelles and buffalo could be seen everywhere. The men often resorted to drinking stagnant pond water that made many of them ill, though food became less of a problem with the presence of game.

The Destruction of Sulayman

By mid-July, 1879, Gessi had finally caught up with Sulayman’s column at a place called Gara. Gessi encamped several hours away, instructing his men to avoid lighting fires and to maintain absolute silence to prevent Sulayman’s scouts from discovering their position.

Sulayman commanded some 700 men at this time, while his lieutenant Rabih had a similar number nearby. At daybreak on July 16, Gessi concealed his force of 275 men in the woods and sent a message to Sulayman’s camp that they were surrounded and had five minutes to lay down their arms and surrender or they would be destroyed. It was yet another example of deception as a weapon; Gessi actually feared that surrounding the much larger group would allow his force to be overrun and instead kept his detachment intact. Believing that Gessi had 3,000 troops and that their own end was imminent, the rebel camp broke into mass confusion, with some fighters fleeing into the woods while most, including the leaders, laid down their arms and surrendered. Sulayman was visibly dismayed when he realized the actual size of Gessi’s force, exclaiming to his captor: “What! Have you no other troops?” [57]

What happened next is still a matter of controversy. The leading prisoners, Sulayman and eleven of his chief advisors, were oddly not bound, the usual practice, suggesting there was some type of agreement between the antagonists. Austrian Rudolf Slatin Pasha (governor of Darfur, 1881-1883) claimed that an officer in the government expedition told him that Gessi had offered Sulayman a pardon in return for his surrender, but this has never been confirmed. [58] In the night Gessi claimed to have received reports that Sulayman and his chiefs were conspiring to escape; according to Gessi, the slave-traders’ horses were found to have been saddled and supplied with food and arms. This uncommon lack of security seems strange, but it supplied Gessi with a justification “to have done with these people once and for all.” [59]

Execution of Sulayman Pasha

Execution of Sulayman Pasha

Sulayman and the chiefs were lined up in front of a firing squad. The young Sulayman reportedly fell to his knees in shock and anguish, but most of the chiefs met their death with dignity and defiance. [60] Gordon took full responsibility for the killings; “I have no compunction about [Sulayman’s] death… Gessi only obeyed my orders in shooting him.” [61] Gessi makes only a fleeting reference to the most important incident in his career in his posthumously published memoir, noting he ordered the executions after an escape attempt. [62] Meanwhile, Rabih had moved off to Dar Banda in the Zande country, going on to carve out his own slave-based empire in central Africa before he was killed and decapitated by French colonial troops and their Baguirmi allies in 1900.

Governor of Bahr al-Ghazal

Having eliminated Sulayman, Gessi was now compelled to turn his attention to the development of Bahr al-Ghazal. His first step was disarming many of his own troops, “who were no less brutal and savage than Suleiman’s troops.” [63] Harsh penalties were promulgated for all slavery-related offences. Public hangings were meant as a deterrent, but much of Gessi’s time was occupied in expeditions against the region’s remaining slavers with only 150 regulars. By now, long exposure to brutality, fever and isolation had helped turn Gessi into a delusional prototype for Conrad’s Colonel Kurtz character in The Heart of Darkness:

I am obliged to rule by fear, and it is quite a miracle that I am still alive. My whole strength lies in the inhabitants, who obey me as if I were their Deity, and, if necessary, I should have more than ten thousand armed men ready to defend and die with me. [64]

Gessi spent over two months of the summer of 1880 bed-ridden by an extremely painful Guinea Worm infection that also brought down many of his officers. During this time, Gessi (like the fictional Kurtz) stopped sending reports to his superiors in Khartoum and failed to organize the administration, creating strains with the administration of Gordon’s replacement, Governor-General Muhammad Ra’uf Pasha. The result was a demotion and cut in pay. [65]

The Death Ship

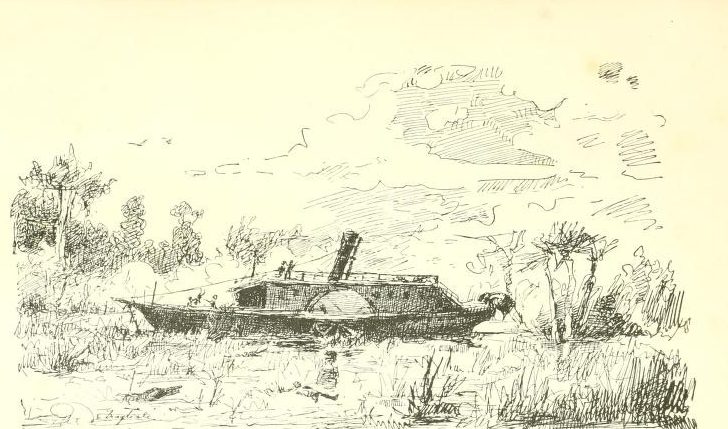

Departing Bahr al-Ghazal on his own initiative on September 25, 1880, Gessi left for Khartoum on the steamer Safiya to defend his actions to Ra’uf Pasha. Gessi ignored advice not to attempt the passage through the 30,000 square kilometer Sudd swamp of south Sudan without a trained crew, proper equipment or a steamer with sufficient power. [66] The Sudd is famous for vast islands of floating vegetation that impede navigation and can easily trap a ship.

The Safiya in the Sudd

The Safiya in the Sudd

Carrying two companies of troops and their families as well as many Danagla Arab traders, the Safiya was a small wood-burning steamer equipped with a 40 horsepower engine, insufficient to force its way through the Sudd. The ship’s tackle and equipment, essential to working the ship through the swamp, had been allowed to rot with neglect. Giegler maintained (likely on the basis of the subsequent inquiry) that the ship’s crew insisted on returning until a better-equipped ship could be sent to cut the way, but Gessi demanded the attempt be made, wanting “to waste no time in reaching Khartoum and Cairo in order to give [Muhammad] Ra’uf and me [Giegler] a slap in the face, as he put it!” [67]

Most of the soldiers and crew believed Gessi’s return to Khartoum was a result of official recall, making it difficult for Gessi to assert his authority aboard the Safiya, especially when food became scarce after the Safiya predictably became trapped in the Sudd.

Sleep on the ship in the midst of clouds of malarial mosquitos was nearly impossible and starving and exhausted men were asked to perform the brutally hard work of entering the swamp to break through the bars of vegetation. Fuel for the steamer ran out and the captain took to his cabin to sell the ship’s stores to starving men at extortionate prices. After having eaten their shoes, the lethargic men laid still on the deck to await their death. Accused of hoarding food, Gessi was forced to keep his weapons close while his native bodyguards slept in the doorway of his cabin. According to Giegler, it was only the protection offered by ivory trader and former Gessi ally Abu Amuri that kept Gessi from being murdered by his own soldiers. [68]

Passengers and crew alike began to die at an alarming rate and were simply pushed overboard, where the stench of their rotting corpses and the arrival of hordes of feeding vultures only increased the misery of those still trapped onboard. By mid-December, nearly three months after departure, Gessi recorded only eight of his 149 Sudanese soldiers still alive:

We have reached the worst. I cannot remember anything like it in all my life. Scarcely does someone die than he is devoured during the night by the survivors. It is impossible to describe the horror of such scenes. One soldier devoured his own son. [69]

On January 5, however, the Safiya was rescued by the steamer Burdayn, sent out by Giegler. Over 430 people had died on the Safiya and Gessi, a “living skeleton,” was held responsible. [70] Results of an investigation considered embarrassing to the reputation of the Egyptian Army were eventually filed away in a dark corner in Cairo. Giegler claimed it was “clear that Gessi and Gessi alone was responsible for the misfortune but this did not worry him at all.” [71]

Desperately sick in Khartoum, Gessi sought to head north to put his case before the Khedive. According to Slatin, Gessi insisted on being accompanied to Cairo by his eunuch al-Mas (likely one of the young eunuchs seized during a raid on a eunuch manufacturing operation that Gessi claimed was run by his second-in-command Yusuf Bey al-Shallali [72]), but Ra’uf Pasha, fearing a scandal, forbade it. [73]

Gessi was still sick and weak when he set out and had to be carried across the burning desert to the port city of Suakin on a litter suspended between two camels. By the time he arrived in Cairo he was clearly dying, and even a last minute personal visit from Khedive Muhammad Tawfiq was not enough to provoke his recovery. He expired on April 30, 1881; in his last note to a friend, Gessi remarked: “I have suffered too much. I have been exposed to too many fatigues. The last catastrophe of the voyage has quite crushed me. Another in my place would have died of horror.” [74] Again, one is reminded of Kurtz’s last words in Heart of Darkness: “The horror! The horror!”

Was Gessi Actually Responsible for the Conduct of the Campaign?

One of the lingering questions regarding Gessi’s Bahr al-Ghazal campaign is the degree of success attributable to Gessi’s second-in-command, Colonel Yusuf Bey al-Shallali (later made a Brigadier and Pasha). Hailing from the village of al-Shallal on the First Cataract of the Nile, Yusuf had worked for Zubayr in Bahr al-Ghazal before receiving a military appointment from the Egyptian government.

According to Giegler Pasha, Yusuf was the “main-doer” on the campaign; “Though Gessi’s name is always connected with the history of the Zubayr Pasha revolt on the Bahr al-Ghazal, it was in fact Yusuf Bey who directed the whole operation. Gessi was responsible only for the end; he had Sulayman al-Zubayr captured and shot after the latter had acted so wildly.” [75] Giegler, like many in the Sudan administration, was not overly fond of the Italian mercenary, but neither did he hold a brief for Yusuf Pasha, who served the government under a certain degree of suspicion due to his reputation as a major slaver. The matter seems fated to remain unresolved; Gessi himself gave Yusuf little credit for his role in the campaign, noting that “my faith in Yusuf Bey as an officer was not great.” [76] Elsewhere Gessi accused Yusuf of the greatest crimes, including murder, slave-raiding, and rampant corruption.

Nonetheless, Yusuf’s performance in the campaign brought him promotion in Khartoum and appointment as governor of Sinnar Province. [77] Yusuf replaced Giegler as military commander under the orders of a new governor-general, ‘Abd al-Qadir Pasha. In May 1881, Yusuf Pasha left Fashoda for the Nuba Mountains with 3500 mostly unwilling troops, four field guns and a rocket battery to put down the incipient Mahdist revolt. Near Jabal Qadir, Yusuf uncharacteristically failed to post sentries around his zariba, allowing thousands of Mahdist troops to infiltrate the camp before attacking the still-sleeping soldiers. Yusuf, still in his underclothes, was killed in front of his tent and the entire Egyptian force wiped out.

Aftermath and Legacy: Tactical Victory, Strategic Failure

Bahr al-Ghazal only remained in government hands for five years after Gessi’s campaign, which inadvertently laid the foundation for the collapse of Turco-Egyptian rule in the region by disrupting the slave-based economy (for which no immediate alternative existed) and alienating many Arab groups. Those who joined the Mahdist rebellion were not, however, the Ja’aliyin Arabs who followed Sulayman Pasha, but rather Danaqla and Baqqara Arabs who had been promised much by Gessi for their support, but ultimately received nothing. Other groups that had been provided arms by Gessi for use against the slavers turned these same arms against Gessi’s successor. Soon after Gessi’s departure Arab slavers and government troops alike began to re-indulge in the slave trade in Bahr al-Ghazal. Nonetheless, Gordon was pleased with Gessi’s efforts: “He has done splendidly, and I am greatly relieved… Gessi had most inadequate means for his work – at least five-sixths of those with him were, in their hearts, friends of Zubayr’s son…” [78]

Gessi was hailed by Italian colonialists shortly after his death as a model anti-slaver and notable explorer. Gessi’s remains were repatriated to Italy in 1883 and laid to rest in Ravenna. The transfer was used by pro-colonialist Italian factions to promote new 19th century Italian colonial adventures in Eritrea and Somalia. Gessi’s legacy was again revived in the 1930s by Fascist leaders seeking to build a new “Roman Empire” in Libya and Ethiopia. World War II’s Battaglione “Romolo Gessi” was an Italian combat unit formed in May 1941 from Italian and Libyan members of the Polizia dell’Africa Italiana (Italian Africa Police), a colonial police force. It was disbanded less than a year later after suffering heavy losses. [79]

In the post-WWII era, Gessi’s accomplishments were folded into an embarrassing and ultimately self-destructive colonial past that most Italians preferred to ignore. The availability of previously unexamined correspondence and documents in the 1980s shed a negative light on Gessi’s work and his often tempestuous relations with colleagues. More recent treatments of Gessi’s life have emphasized his weaknesses as an explorer, administrator, businessman and, most harshly, as a soldier. [80]

Conclusion: Lessons Learned in Counter-Insurgency

Though Gessi never explicitly described the actual lessons he might have learned over a year in the bush fighting highly capable and well-supplied insurgents, it is nevertheless possible to list those principles which served Gessi (and Yusuf) in their campaign:

- Make liberal use of intelligence gained from deserters, prisoners and civilians hostile to the enemy

- Impose iron discipline tempered by regard for local habits and customs

- Adapt to local means of warfare by using ambushes, guerrilla tactics and mobile strike forces

- Keep your force lean and avoid the use of undisciplined irregulars whenever possible

- Employ ruthlessness as a force multiplier

- Use deception whenever possible to even the odds against a superior enemy

- Exploit local grievances to cut support for the insurgents

- Improvise to cover weaknesses in supply and logistics systems

- Offer economic alternatives to cooperation with the insurgents

Gessi was often hard-pressed to assert his authority over his own men as well as the enemy. In the circumstances, Gessi turned to severe discipline in the first case and ruthlessness in the second. Gessi later remarked:

I was the only Christian among all the Mohammedans whom I led against other Mohammedans, and who at any moment might have revolted and left me at the mercy of the enemy. Notwithstanding this exceptional positon, I used the utmost rigor against everyone. This discipline, and above all, Divine Providence, enabled me to succeed. [81]

As far as Gessi’s campaign was remembered at all in the U.K., it was mainly as an episode of the larger 19th century anti-slavery movement, while in Italy it was (in the pre-WW II era at least) an example of Italian superiority over the “lesser races” of Africa. The campaign’s controversies, the absence of other European troops, Gessi’s own death and the subsequent collapse of Egyptian authority in the Sudan did little to recommend its study in European military academies. As a result, many of the lessons that could have been drawn from the campaign had to be relearned later, initially by Belgian forces fighting their own war against Arab slavers in the Congo in the 1890s, and later by French officers like Colonels Roger Trinquier and David Galula, who developed modern counter-insurgency strategies during the bitter Indo-Chinese and Algerian insurgencies.

Colonel Galula described victory in counterinsurgency as “the permanent isolation of the insurgent from the population, isolation not enforced upon the population, but maintained by and with the population.” [82] In this sense, Gessi fell well short of ultimate victory; dissatisfaction created by Gessi’s failure to follow through on promises to his Arab allies helped promote the broader, religiously-inspired Mahdist rebellion that killed Gordon and expelled the “Turks” from the Sudan only a few years later. As the U.S. counterinsurgency manual notes, “killing insurgents—while necessary, especially with respect to extremists—by itself cannot defeat an insurgency.” [83]

Bibliography

Abbas Ibrahim Muhammad Ali: The British, the Slave Trade and Slavery in the Sudan 1820-1881, Khartoum University Press, 1972

Azevedo, M. J.: The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad, Routledge, 2005

Barrows, Leland: Review of Zaccaria, Massimo, “Il Flagello degli schiavisti” Romolo Gessi in Sudan (1874-1881) con trentatre lettere e dispacci inediti. H-Africa, H-Net Reviews. November, 2001, http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=5654

Berlioux, E. Felix: The Slave Trade in Africa in 1872 (Trans. Joseph Cooper), London, 1873

Casati, Gaetano: Ten years in Equatoria and the return with Emin Pasha, 2 volumes, Brothers Dumolard, Milan, 1891

Chenevix-Trench, Charles: The Road to Khartoum: A Life of General Charles Gordon, Norton, New York, 1978

Clausewitz, Carl von: On War, Princeton University Press, 1989

Cordell, Dennis: Dar Al-Kuti and the Last Years of the Trans-Saharan Slave, University of Wisconsin Press, 1985

Crociani, P., and P.P. Battistelli, Italian Army Elite Units & Special Forces 1940-43, Osprey Publishing, London, 2011

Ewald, Janet J.: Soldiers, Traders and Slaves: State Formation and Economic Transformation in the Greater Nile Valley, 1700-1885, University of Wisconsin Press, 1990

Fawzi, Ibrahim, James Davidson Deemer and Zohaa el Gamaal: Kitab al-Sudan bayna aydi Gordon wa Kitchener: 1291-1302, (The History of the Sudan between the Times of Gordon and Kitchener: 1291-1302), al-Bayt University, Mafraq (Jordan), 1997. (First publication Cairo 1901)

Gessi Pasha, Romolo: Seven Years in the Soudan; Being a Record of Explorations, Adventures and Campaigns against the Arab Slave Hunters, (Sette anni nel Sudan egiziano), London, 1892

Giegler Pasha, Carl C.G (ed. by R.L. Hill): The Sudan Memoirs of Carl Christian Giegler Pasha 1873-1883, Oxford University Press, London, 1984

Gray, R: A History of the Southern Sudan, 1839-1889, Oxford University Press, 1970

Hill, George Birkbeck: Colonel Gordon in Central Africa, 1874-1879, Thos. De La Rue & Co., London, 1881

Hill, Richard: Egypt in the Sudan, 1820-1881, Oxford, 1959

Hill, Richard: Biographical Dictionary of the Sudan, (2nd ed.), Oxford, 1967

Hill, Richard L.: “A Register of Named Power-Driven River and Marine Harbour Craft Commissioned in the Sudan, 1856-1964,” Sudan Notes and Records 51, 1970, pp. 131-146.

Hinde, Sidney Langford: The Fall of the Congo Arabs, Methuen, London, 1897

Jackson, HC: Black Ivory: The story of El-Zubeir Pasha as told by himself (Trans. and recorded by HC Jackson), Khartoum, 1913

Mire, Lawrence: “Al-Zubayr and the Zariba Based Slave Trade in the Bahr al-Ghazal, 1855-1879,” in: John Ralph Willis (ed.): Slaves and Slavery in Africa Volume Two: The Servile Estate, Frank Cass and Co., London, 1985, pp. 101-12

Mohamed Omer Beshir: The Southern Sudan: Background to Conflict, C. Hurst & Co., London, 1968

Moore-Harell, Alice: Gordon and the Sudan: Prologue to the Mahdiyya, 1877-1880, Frank Cass, London, 2001

Mowafi, Rita: Slavery, Slave Trade and Abolition Attempts in Egypt and the Sudan, 1820-1882, Lund Studies in International History 14, Scandinavian University Books, Maimö, 1981

Powell, Eve Troutt: A Different Shade of Colonialism: Egypt, Great Britain, and the Mastery of the Sudan, University of California Press, 2003

Reis, Bruno C.: “David Galula and Roger Trinquier: two warrior-scholars, one French late colonial counterinsurgency?” in: Andrew Mumford and Bruno C. Reis (ed.s), The Theory and Practice of Irregular Warfare: Warrior-scholarship in counter-insurgency, Routledge, London, 2014, pp.35-69

Schweinfurth, G: The Heart of Africa: Three Years Travel in the Unexplored Regions of Central Africa (2 vol.s), Harper and Brothers, New York, 1874

Shaw, Flora L.: “The Story of Zebehr Pasha as told by himself: Part III,” Contemporary Review 52, 1887, pp. 658- 682.

Shukry, MF: The Khedive Ismail and Slavery in the Sudan, 1863-1879, Cairo, 1938

Slatin Pasha, Rudolf: Fire and Sword in the Sudan (Trans. by FR Wingate), London, 1896 (page numbers in footnotes refer to the Arnold edition of 1930)

Theobald, A.B.: The Mahdīya: A History of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1881-1899, Longman’s, London, 1951

Thomas, Edward: The Kafia Kingi Enclave: People, Politics and History in the North-South Boundary Zone of Western Sudan, Rift Valley Institute, 2010

Thomas, Frederic C.: Slavery and Jihad in the Sudan: A Narrative of the Slave Trade and its Legacy, iUniverse, 2009

U.S. Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2007, http://usacac.army.mil/cac2/Repository/Materials/COIN-FM3-24.pdf

Udal, John O.: The Nile in Darkness Volume II: A Flawed Unity, 1863-1899, Michael Russell, Norwich, 2005

Zaccaria, Massimo: “Il Flagello degli schiavisti” – Romolo Gessi in Sudan (1874-1881) con trentatre lettere e dispacci inediti, Fernandel scientifica, Ravenna, 1999

Zaghi, Carlo: Vita de Romolo Gessi, ISPI, Milan, 1939

Zavatti, Silvio: “Giovinezza di Gessi”, Corriere Padano, August 1939

NOTES

[1] Cited in Udal, vol. ii, p. 346

[2] GB Hill, p.373

[3] Giegler, p.163

[4] Ibid, p. 28

[5] Ibid, p. 28

[6] Gessi, p.316

[7] Ibid, p.317

[8] Ibid, p. 125

[9] Giegler, p. 110

[10] Ibid, p. 49

[11] Ibid, p. 104

[12] Mowafi, p.56

[13] Berlioux, p.20

[14] Cited in Udal, p. 338

[15] Gessi, pp. 51-52

[16] Udal, vol.II, p. 170

[17] Shaw, p.674

[18] Ibid, p. 681

[19] Gessi, pp. 247-50

[20] GB Hill, p.372; Gessi, p.305

[21] Shaw, p.677

[22] Gessi, p.301

[23] Ibid, p.186

[24] Ibid, p. 344

[25] GB Hill, p. 343

[26] Ibid, p.373

[27] Gessi, p. 187; Giegler, p.117

[28] Gessi, p.288

[29] Ibid, p.190, pp. 355-57

[30] Ibid, p.194

[31] Shaw, p. 678

[32] Gessi, p.27; GB Hill, p.350

[33] GB Hill, p.370

[34] Schweinfurth, Vol. II, p.423

[35] Gessi, pp. 234-35

[36] Ibid, p.235

[37] GB Hill, p.375; Gessi, p.289

[38] Gessi, p.255

[39] Gessi, p.240; GB Hill, p.377

[40] Ibid, pp. 241-42

[41] Ibid, 242-43

[42] GB Hill, p.378

[43] Gessi, p.263

[44] Ibid, p.263

[45] Ibid, p. 268

[46] Ibid, p. 271

[47] Ibid, p. 270

[48] Ibid, p.307

[49] Ibid, p. 282

[50] Von Clausewitz, p.203

[51] Gessi, p. 286

[52] GB Hill, pp.384-385

[53] Gessi, p. 328

[54] Ibid, pp. 328-29

[55] GB Hill, p.370

[56] Gessi p. 350

[57] GB Hill, p.387

[58] Udal, v.ii, p.351

[59] GB Hill, p.387

[60] Ibid, p.387

[61] Cited in Udal, vol.ii, p. 351

[62] Gessi, p. 329. The number of chiefs arrested by Gessi differs from eight to eleven according to various accounts.

[63] Ibid, p. 359

[64] Ibid, p. 365

[65] Giegler, p.158

[66] Ibid, p.158

[67] Ibid, pp. 158-59

[68] Ibid, p. 159

[69] Gessi, p. 401

[70] Austrian Consul Martin Hansal, cited in Udal, Vol. II, p.369

[71] Giegler, p.160

[72] Gessi, pp. 355-357

[73] Slatin, p.35

[74] Gessi, pp. 416-17

[75] Giegler, pp. 117, 147

[76] Gessi, p. 207

[77] Giegler, p.117, fn. 11

[78] GB Hill, p. 348

[79] Crociani and Battistelli, p. 20

[80] See esp. Zaccaria.

[81] Gessi, p. 346

[82] Galula, p.57

[83] U.S. Army/Marine Corps, p.1-14

This article first appeared in Military History Online on August 21, 2016: http://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/19thcentury/articles/inventionofcounterinsurgency.aspx#

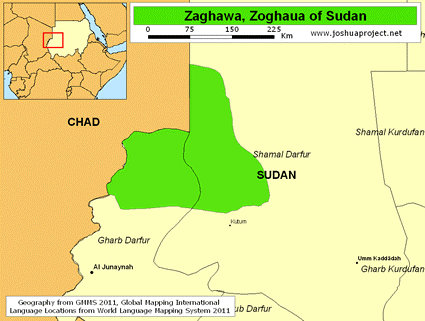

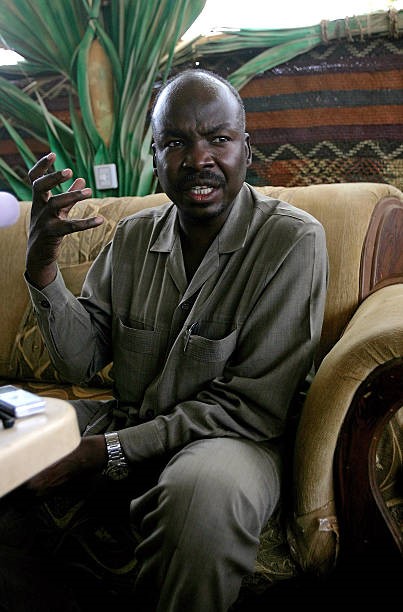

Ahmad Muhammad Harun as Governor of South Kordofan

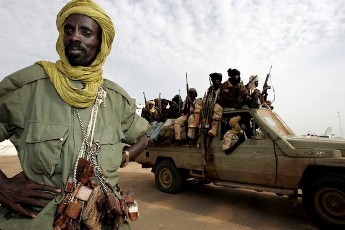

Ahmad Muhammad Harun as Governor of South Kordofan Janjaweed Gunmen in Darfur, 2008 (Andrew Carter)

Janjaweed Gunmen in Darfur, 2008 (Andrew Carter) Commander ‘Abd al-Aziz al-Hilu (Paulo Nunes dos Santos/Polaris)

Commander ‘Abd al-Aziz al-Hilu (Paulo Nunes dos Santos/Polaris) A spokesman for Darfur’s rebel Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) was unsurprised at the time that Harun had been appointed governor of South Kordofan: “Having orchestrated the Darfur genocide, Harun is the right choice for the Government of Sudan to complete the unfinished job to ethnically cleanse the Nuba People and bring in Arabs to occupy their lands” (Sudan Tribune, June 21, 2011).

A spokesman for Darfur’s rebel Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) was unsurprised at the time that Harun had been appointed governor of South Kordofan: “Having orchestrated the Darfur genocide, Harun is the right choice for the Government of Sudan to complete the unfinished job to ethnically cleanse the Nuba People and bring in Arabs to occupy their lands” (Sudan Tribune, June 21, 2011).