Andrew McGregor

December 8, 2008

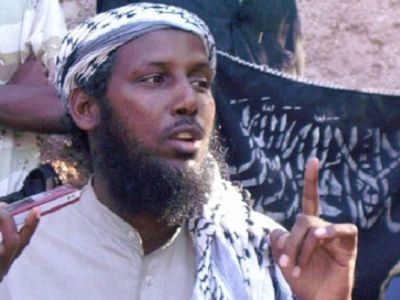

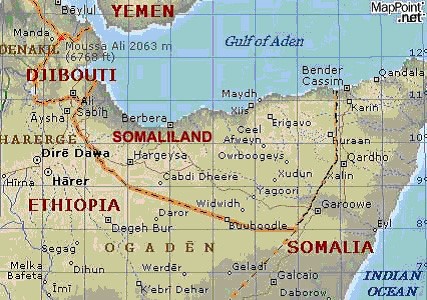

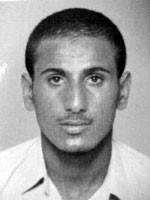

With the completion of a month-long police investigation, Somaliland’s Interior Minister, Abdullahi “Irro” Ismail, has announced al-Shabaab extremists are responsible for the suicide bombings that killed more than 20 people in Somaliland’s capital of Hargeisa in late October. Al-Shabaab, originally the youth wing of Somalia’s Islamic Courts Union (ICU) movement, has emerged as the most militant faction of the Islamist resistance. According to the Interior Minister, the three suicide bombings that targeted the presidential palace, the Ethiopian trade office and the regional UN offices were organized by al-Shabaab leaders Mukhtar Robow “Abu Mansur” and Ahmad Abdi Godane “Abu Zubayr,” the latter a Somaliland native who trained with al-Qaeda in Afghanistan.

Ahmad Abdi Godane “Abu Zubayr”

Ahmad Abdi Godane “Abu Zubayr”

Among those killed by the car-bombs were the President’s personal secretary and senior anti-terrorism official Ibrahim Hutu. The actual operation was supervised by a man known as Abdulfatah Abdullahi Guutaale. Ismail added; “Somaliland’s enemy, from day one to today, has always been al Shabaab” (Garowe Online, November 27; AFP, November 27). A noted Somaliland Muslim leader, Shaykh Ali Warsame, condemned the attacks as outrageous and un-Islamic (Somaliland Times, November 1). The bombings may have been designed to interfere with upcoming elections next March.

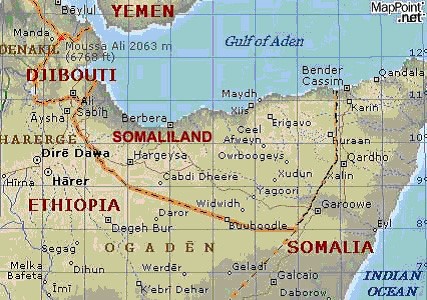

The investigation revealed that of the six suicide bombers involved in the October 29 attacks, only one was from Somaliland, while the other five hailed from Somalia proper. Somaliland, roughly corresponding to the borders of colonial-era British Somaliland, split from Somalia in 1991 following the fall of the Siad Barre regime. As the rest of the country plunged into violence and political chaos, Somaliland created a stable state with democratic elections, but has failed completely in gaining international recognition. Somaliland’s security services are in admitted need of international assistance and training, but Somaliland’s non-sovereign status prevents any such efforts.

At the same time as the Hargeisa explosions, other suicide bombings occurred in neighboring Puntland, a semi-autonomous district of Somalia. A pair of suicide car bombs struck two anti-terrorism offices of the Puntland Intelligence Service (PIS) in Bosasso, the economic capital of Puntland. The huge blasts, which Puntland also blamed on al-Shabaab, killed six PIS agents (AFP, October 30).

A Planned Attack

A Planned Attack

A document from the ICU’s Shura Council dated September 28, 2006 and signed by Shaykh Dahir Aweys, called for the ICU “to send 30 young martyrs to carry out explosions and killing of the Jewish and American collaborators in the northern regions” (Awdal News Network, October 17, 2006). The Arabic language document included a list of thirteen prominent Somaliland politicians targeted for assassination (including President Dahir Riyale Kahin), all of whom are accused of apostasy by abandoning Islam to work with Americans and Jews. The decision came after ICU leaders viewed a video purporting to show the torture of Shaykh Muhammad Ismail by Somaliland security officials. Somaliland officials described the tape as a fake. The Shaykh was charged earlier with involvement in an attempt to disrupt the September 2005 elections with bombings.

Some of Somalia’s Islamists are intent on integrating Somaliland into a “Greater Somalia” that would also include Ethiopia’s Ogaden region, semi-autonomous Puntland, Djibouti and north-eastern Kenya.

Determining Responsibility

The day after the bombings, al-Shabaab posted a videotape to jihadi websites showing the last testament of one of the suicide bombers, though al-Shabaab did not explicitly claim credit for the attacks. The young man pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda leaders Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri and called for the expulsion of all foreigners in Somalia, especially Ethiopian troops and African Union peacekeepers. Two of the suicide bombers were identified by name; Abul Salam Hersi and Abdul-Aziz Saad, both of whom were members of the Hawiye/Habr Gidir Ayr sub-clan, which supplies many of the Islamist fighters engaged in the struggle for Mogadishu (al-Jazeera, October 30; Somaliland Times, November 1).

U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Africa Jendayi Frazer suggested al-Qaeda was the responsible party; “Nobody has claimed responsibility for the attacks, but they have the markings of al-Qaeda … We believe that these senseless attacks highlight the determination of violent extremists to undermine peace and stability throughout Somalia and the Horn of Africa” (AFP, October 29).

Frazer, however, failed to mention the American connection to the suicide attacks. It’s believed that one of the suicide bombers was 26-year old Shirwa Ahmed, a naturalized U.S. citizen and resident of Minneapolis, home to a substantial Somali émigré population. Ahmed moved to Minnesota in 1996 and graduated high school there before becoming one of over a dozen young Somali men to disappear from the area in recent months. All are believed to have returned to Somalia to join the fighting, possibly as suicide bombers. FBI officials will not confirm whether an investigation is under way (Minneapolis-St. Paul Star Tribune, November 25; KSTP-TV [St.Paul], November 29; WCCO-TV [Minneapolis-St.Paul], November 26; AP, November 26). Abdulfatah Abdullahi Guutaale, the local organizer of the Hargeisa bombings, once lived in the Minneapolis area and may have a U.S. green card, according to the Somaliland Interior Ministry investigation (AFP, November 27).

Accusations that Somaliland officials were harassing refugees from Somalia following the blasts were denied by the government (Shabelle, November 17). Interior Minister Abdullahi Ismail Irro issued a statement urging Somalilanders to take possible suspects to the nearest police station instead of taking the law into their own hands (IRIN, November 10). Another victim of the bombings was Somaliland’s voter registration campaign, which has now been suspended.

Prior al-Shabaab Activities in Somaliland

In December 2006, a major trial ended in Somaliland in which 15 suspects were charged (six in absentia) with conspiracy to commit terror, illegal importation of arms and explosives and the wounding of three policemen in September/October 2005. Most of the suspects were convicted and sentenced to 20 – 25 years in prison. Among those sentenced to 25 years was Shaykh Muhammad Ismail, a leading Islamist radical. Two of the others sentenced in absentia were Ahmad Abdi Godane “Abu Zubayr” (a suspect in the latest Hargeisa attacks) and Ibrahim Jama Afghani, another veteran of the anti-Soviet war in Afghanistan (Somaliland Times, December 9, 2006).

Surprisingly, both Shaykh Hassan Dahir Aweys and Aden Hashi Farah “Ayrow,” an Afghanistan veteran and military commander of al-Shabaab, were acquitted due to a lack of evidence. The two were tried in absentia. Aden Hashi was killed in a U.S. airstrike on his home last May. Shaykh Hassan Dahir Aweys is a former colonel in the Somali army and the leader of what might be termed the “rejectionist” faction of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), taking a hard-line on peace efforts while calling for the destruction of Somalia’s Transitional Federal Government (TFG) and the expulsion of all foreign troops. Aweys is an inflexible opponent of Somaliland’s struggle for independence; “People in Somaliland worship a deity called “Peace” and this deity is mirrored on Western ideology…” (Somaliland Times, December 9, 2006).

The al-Shabaab threat has been used for political purposes within Somaliland. A wave of bombings struck Hargeisa in April, including a grenade attack on the home of a cabinet minister and a large bomb that caused heavy damage to one of Somaliland’s houses of parliament, the House of Guurti (elders). The government blamed the opposition Kulmiye party (Garowe Online, April 10). In August, Interior Minister Irro accused a leading member of the opposition Kulmiye party of being a member of al-Shabaab. The arrest of Hersi Ali Haji Hassan followed his criticism of an exclusive livestock export deal made by the Somaliland president with a Saudi Arabian company. The Kulmiye party responded by accusing the President of damaging the region’s peaceful image (Garowe Online, August 12). Raising livestock is a major industry in Somaliland and the President’s grant of a monopoly on exports to a Saudi firm brought charges from the opposition of violating the constitution and even “high treason,” an impeachable offense (Garowe Online, July 29).

A Low Level War with Puntland

Somaliland is also engaged in a bitter dispute with Puntland over the Sool and Sanaag regions, which both territories claim. A local insurgent group fighting to end Somaliland’s “occupation” of the Sool region, the Somali Unity Defense Alliance (SUDA), appears to be a thinly veiled Puntland proxy. Such accusations are denied by the group’s leader, Colonel Abdiaziz “Garamgaram” Muhammad, who is best known as a former commander in the militia of notorious warlord and accused war criminal Muhammad Said Hersi Morgan while the latter was fighting the Juba Valley Alliance for control of the port of Kismayo (now in the hands of al-Shabaab) (Garowe Online, September 10). Colonel Muhammad’s predecessor, Colonel Deyr Abdi, was captured by Somaliland security forces when they raided a gathering of pro-Puntland militias at the regional capital of Las Anod last January. Colonel Abdi had been appointed military commander of the region by Puntland’s ruler, General Adde Musa. A column of Somaliland troops in 20 armored trucks under Colonel Hashi Yare seized the coastal town of Las Qorey last July after Puntland troops withdrew to the east (Garowe Online, July 9).

Conclusion

Somali insurgents, including al-Shabaab, regard the Hargeisa government as being U.S. and Ethiopian backed. Somaliland authorities again became hopeful international recognition might at last be on the way when U.S. Assistant Secretary for African Affairs Jendayi Frazer met with the Somaliland president for security talks last February. The meeting followed a visit by President Dahir Rayale to Washington the previous month. The October 29 blasts will undermine Somaliland’s projection of an image of security and damage its prospects for recognition. The consequent withdrawal of United Nations personnel leaves Somaliland more isolated than ever. There are fears that Islamist extremism may gain ground in Somaliland if recognition of Somaliland’s independence continues to be withheld. Italy and a handful of African countries pose the main opposition to Somaliland’s independence.

This article first appeared in the December 8, 2008 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor

Osama al-Kini (a.k.a. Fahid Muhammad Ali Msalam)

Osama al-Kini (a.k.a. Fahid Muhammad Ali Msalam)