Andrew McGregor

February 11, 2009

Flush with petrodollars and beset by regional insurgencies and a possible resumption of the North-South civil war, Khartoum has become an important consumer of foreign arms despite a widely ignored international embargo. The Sudanese military is embarking on a massive modernization campaign and appears to have found a willing partner in Russia, which seeks to extend its influence in Africa and find new customers for Russia’s active arms industry as sales to China drop off dramatically. China has also become Russia’s main competition in arms sales to Africa and is frequently able to supply Chinese-built Russian-designs for significantly less than Russia’s arms industry.

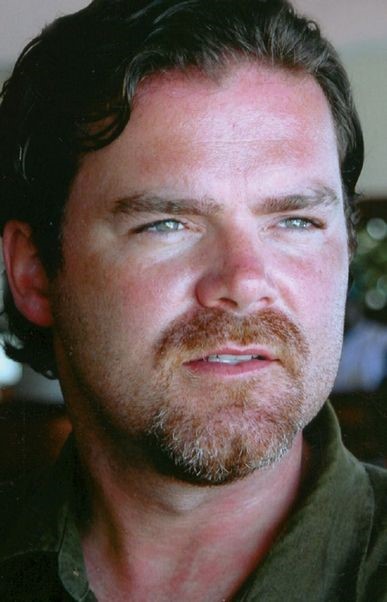

Mikhail Margilov and President Omar al-Bashir

Mikhail Margilov and President Omar al-Bashir

Aside from arms shipments, Russian trade and investment in Sudan is minimal – part of the ongoing legacy of the Cold War and the Soviet Union’s often heavy-handed approach to Africa. A failed coup attempt by the Sudanese Communist Party in 1971 that led to the execution of most of the party’s leadership and the Soviet occupation of Muslim Afghanistan in the 1980s left a climate of strained relations between the two countries. Relations have improved recently as Moscow joined China in opposing the deployment of UN peacekeepers to Darfur.

One sign of the importance Moscow now places on its relations with Sudan was the Russian president Dmitry Medvedev’s appointment last December of a special envoy to Khartoum, Mikhail Margilov, head of the Russian Federation Council’s foreign affairs committee. Margilov has stated Russia must re-establish its presence in Sudan and Africa by being an active participant in conflict resolution (RIA Novosti, December 8, 2008). The new envoy has already made visits to Darfur and the southern capital of Juba (Sudan Tribune, January 31). Following a meeting with Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, Margilov announced Moscow’s intention to sponsor an international conference on Darfur later this year “to review the positive developments in Darfur.” Margilov did not elaborate on the nature of these “positive developments,” but added that Russia is now “actively engaged on Sudan issues and wants to play an active role in the UN Security Council (UNSC), Africa and in world affairs” (SUNA, January 30).

Last November, Sudan’s Defense Minister, Abdul Rahim Muhammad Hussein, confirmed the sale of 12 Russian MiG-29 fighter jets to Sudan (RIA Novosti, November 14; AFP, November 14). Foreign Minister Hussein rejected American criticism of the sale, “It is not for the U.S. to determine what our priorities should be. We know what our country needs” (Sudan Tribune, November 16, 2008).

The Sudanese Defense Minister was in Moscow at the time, where he also invited Russian oil companies to invest in Sudan (Sudan Tribune, December 22, 2008). So far, Russia’s only interaction with Sudan’s growing energy sector came in 2002, when the Russian-Belarusian oil company Slavneft signed a $126 million production-sharing agreement with Sudan for oil exploration, but the project later fell through (Pravda, January 18, 2002). Since then, Sudan’s oil industry has been dominated by oil firms from China, Malaysia and India, but Russia is interested in exporting its oil operations expertise (Russia is the world’s second-largest oil producer).

Russia has successfully cornered the Sudanese market for modern warplanes. In 2001, Russia signed a $120 million deal with Sudan to supply ten MiG-28SE fighters and two MiG-29UB (a dual-seat trainer), which were delivered by 2003-2004 (Kommersant, August 16, 2006).

Sudan took delivery of 12 Russian MiG-29s in July 2004. The delivery was made five months early to avoid potential problems with a UN arms embargo, which was still under debate at the time. The sale was immediately criticized by the United States, which, despite extensive cooperation between the CIA and Sudanese intelligence, officially considers Sudan a sponsor of international terrorism. Asked about reports of the delivery of Russian warplanes to Sudan, a U.S. State Department spokesman replied:

The United States opposes all arms transfers to Sudan, which is a state sponsor of terrorism. Any transfer of lethal military equipment to state sponsors of terrorism is sanctionable under U.S. laws. In addition to U.S. law regarding lethal military equipment transfers to state sponsors of terrorism, the current crisis in Darfur, particularly the continuing violence, is cause for strong opposition to any transfers to Sudan (U.S. Dept. of State, Office of the Spokesman, July 22, 2004).

It is thought the fighters came from a stock of 200 MiG-29s kept at the MiG assembly plant at Lukhovtsy since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Russia was trying to sell these surplus fighters to Algeria and Yemen as well (Moscow Times, July 27, 2004).

Fourteen MiG-29 Fulcrums were supplied to Sudan in 2006, along with Russian trainers, who are rumored to have also flown combat missions against the Darfur rebels. A former Russian air-force pilot was killed when his MiG-29 was shot down on May 10, 2008 during an attack on Omdurman by rebels belonging to Darfur’s Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) (Echo Moskvy, May 28, 2008; Interfax, May 29, 2008; Sudan Tribune, May 29, 2008).

A Khartoum newspaper, Alwan, was closed by authorities after reporting the loss of the Russian aircraft and pilot. Alwan‘s editor was charged with disclosing “sensitive military information harmful to the country’s security and its accomplishments” (Sudanese Media Center, May 14, 2008; Sudan Tribune, May 16, 2008). There have been reports of Sudanese fighter pilots who (like most of the military) hail from Darfur refusing to carry out missions against the Darfur rebels, creating an urgent need for experienced pilots in the Sudanese air-force (Sudan Tribune, May 30, 2008).

In July 2008, 12 MiG-29 Fulcrum jet fighters were reported to have been shipped either from or through Belarus in cargo planes to a military airbase north of Khartoum (Sudan Tribune, July 21, 2008; RIA Novosti, July 21, 2008). Russia’s state arms exporter Rosoboronexport denied supplying the MiG-29s “either directly or indirectly” (Moscow Times, July 23, 2008). A spokesman for the Belarus Ministry of Defense described the reports as a “hoax,” adding; “I do not see a point in commenting on stupidity (Pravda, July 21, 2008).

Most of Sudan’s MiGs are based at Wadi Sayidna military airport, just north of Khartoum. JEM rebels reported attacking the airbase on their way to Omdurman last May, seizing a large quantity of modern arms (Sudan Tribune, May 11, 2008).

The Sudanese Air Force is eager to phase out its half-dozen decrepit Soviet-era Antonov AN-24 and AN-26 transport aircraft, which it has used as modified bombers in South Sudan and Darfur by rolling “barrel bombs” out the cargo door. Many other Soviet-supplied aircraft are at least 40 years old and no longer fit to operate in Sudan’s difficult conditions. A number of Russian-made MiG-23BN fighter-bombers obtained as Libyan surplus have been phased out of service (Kommersant, August 16, 2006). Russia has the advantage of supplying aircraft that are modern but familiar to Sudanese pilots. Khartoum’s main interest is in ground-attack aircraft, the only use Sudanese warplanes have ever received.

Russia has also supplied Mi-17 and Mi-24 helicopter gunships to replace Sudan’s ancient Soviet-era Mi-4 and Mi-8 helicopters. Several of these have been spotted in use in Darfur despite being delivered after the UN arms embargo on Darfur. Sudanese military helicopter pilots are trained under contract at the helicopter training center in the Russian town of Torzhok (Tver Oblast).

Russian and Ukrainian crews also operate most of the commercial aircraft in use in Sudan today. In 2005, Antonov opened a large technical maintenance center in Khartoum for the Antonov aircraft already in operation in Sudan and expected new purchases of AN-74s, designed for operation in hot climates (National Radio Company of Ukraine, November 18, 2005).

This article was first published in the February 11, 2009 issue of the Eurasia Daily Monitor