Andrew McGregor

AIS Historical Background Report

December 3, 2025

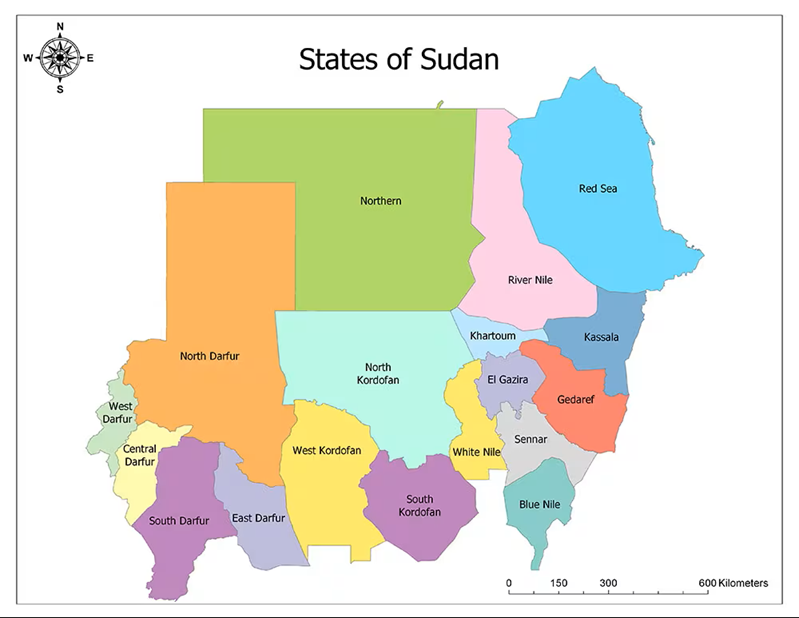

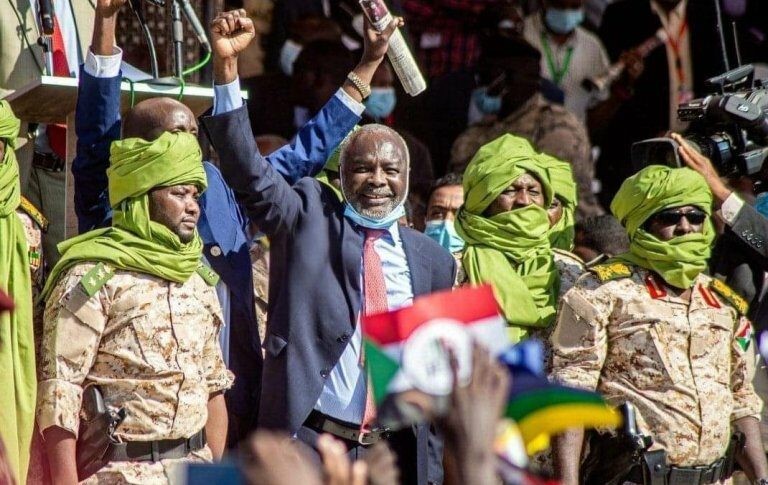

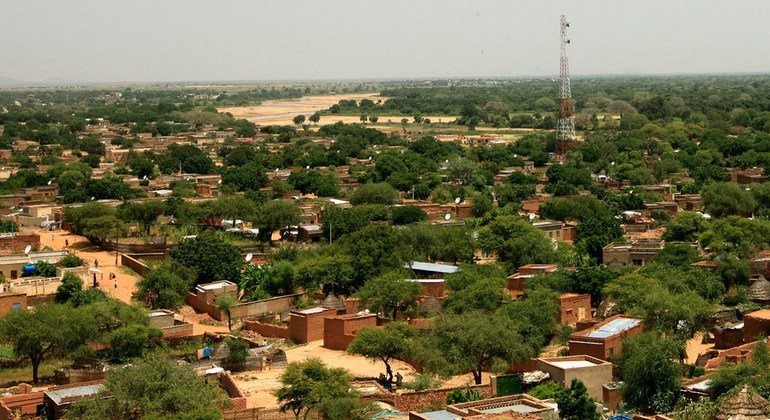

Fighters of Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) entered the North Darfur capital of al-Fashir in late October, launching a wave of atrocities based on ethnic persecution of non-Arab tribal groups in Darfur. The 18-month siege of al-Fashir that preceded these terrible events bore many parallels to the first siege of the city in 1884, one in which many Arab ancestors of current RSF personnel participated as followers of the Sudanese Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad. Then, as now, most of the besieged were non-Arab and faced a similar fate when their defenses were overrun.

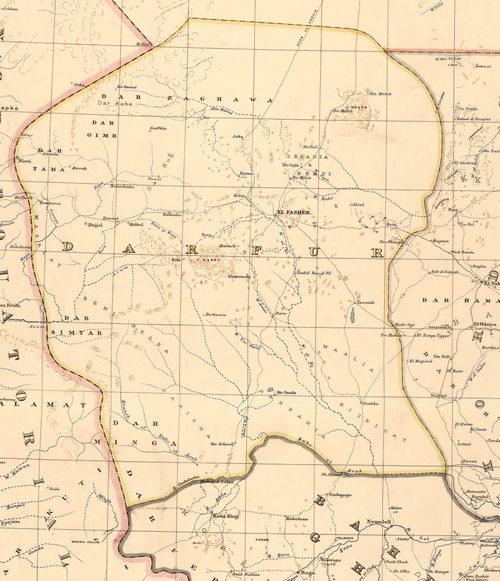

Map of the Sultanate of Darfur, 1914

Map of the Sultanate of Darfur, 1914

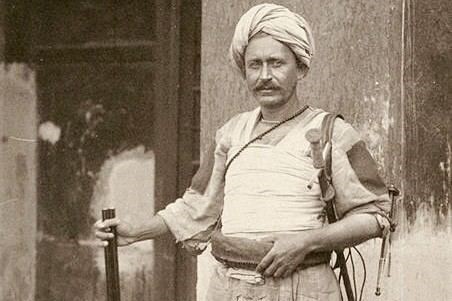

With the encouragement of his Ta’ashi Arab deputy, ‘Abd Allahi, Muhammad Ahmad proclaimed himself the expected Mahdi in 1881. The Mahdi as a messianic figure who appears at the end of time to restore justice in an oppressive world before the arrival of the Nabi Isa (the Prophet Jesus) figures prominently in both Sunni and Shi’ite eschatology (the study of final judgment and the last days of mankind).

Pious and charismatic, Muhammad Ahmad put himself at the head of a growing rebellion against the massively unpopular rule of Egypt’s Turko-Egyptian elite. The Turko-Egyptians invaded Sudan in 1821, replacing numerous chiefdoms and kingdoms with their own rule, one that was at once parsimonious, rapacious, grasping, incompetent and exploitative. Besides brutal methods of tax collection, the new elite angered many Sudanese by their interference in the slave trade, a thriving institution in Sudan. This interference was made more irksome by Egyptian Army officers who appeared publicly to be working to end slavery while making immense profits through their own covert involvement in the trade.

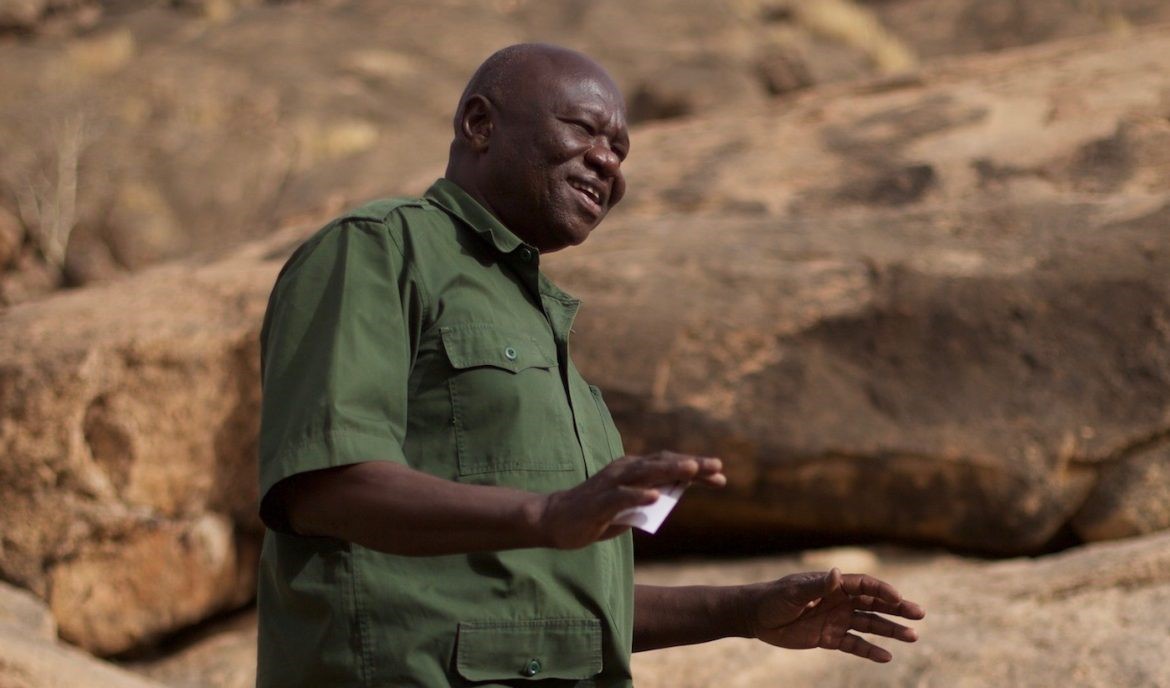

Muhammad Ahmad, the Sudanese Mahdi

Muhammad Ahmad, the Sudanese Mahdi

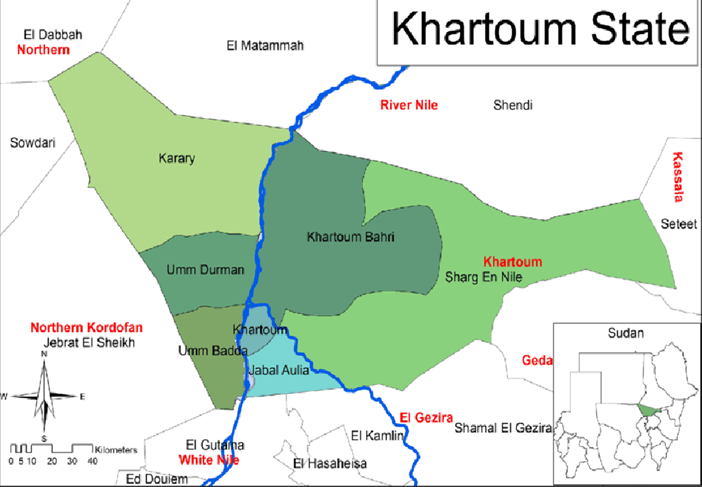

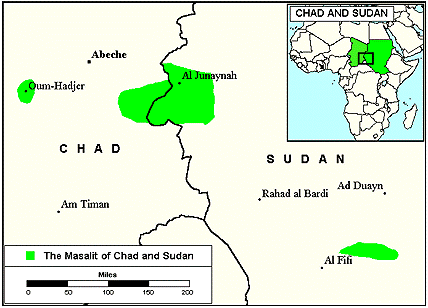

A former Sufi, Muhammad Ahmad was a Dongolawi (one of three powerful groups of Arabized Nubians, including the Ja’alin and the Sha’iqiya) from northern Sudan. He began to attract followers, the so-called ansar (“supporters,” i.e., of religion), at his base on Aba Island in the White Nile. Forced from Aba by government troops, the Mahdi and his followers fled to the Nuba mountains of southern Kordofan and later into the plains of northern Kordofan, where they began besieging towns held by Turko-Egyptian troops, including local recruits, many of whom were Blacks taken as slaves by government-backed slaving expeditions. With Kordofan largely under Mahdist control, Muhammad Ahmad turned his attention west to the old sultanate of Darfur, a powerful Muslim kingdom since its foundation by the Fur people of Jabal Marra in the 17th century, but under Egyptian control since 1874. Al-Fashir, the sultanate’s capital, was established by Sultan ‘Abd al-Rahman in 1792 in the plains east of the mountainous Fur homeland of Jabal Marra. Formerly, the Fur sultans had maintained a peripatetic court, roaming the hills of Jabal Marra.

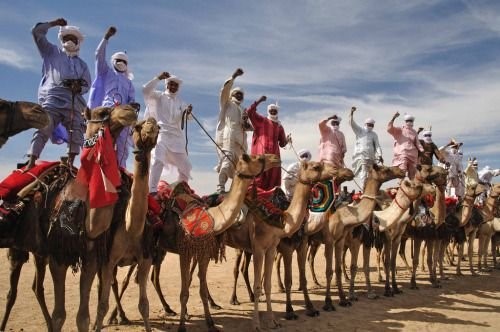

After many years of expansion, Darfur was nearly two-thirds non-Fur by the time of the 1884 siege. Intermarriage with non-Fur ethnic groups had been encouraged in the royal family as a means of consolidating political control, and by the latter half of the 19th century the royal family was probably as much Zaghawa by blood as Fur. Fur was still the court language, but Arabic was the language of official correspondence. A willingness to bring non-Fur into important administrative positions, a reliance on slave labor and a high tolerance for pre-Islamic religious practices helped maintain the Fur royalty. The main dissenters were the nomadic Baqqara (cattle-herding) Arabs of southern Darfur, who maintained their independence by retreating into the marshes along the border with the southern region of Bahr al-Ghazal whenever the sultan decided it was time to send out a punitive column to bring them in line. Repeated clashes grew into bitterness on both sides, a situation that only deteriorated under the rule of the Turko-Egyptians, leaving both the Baqqara tribes and their northern Abbala (camel-herding) Arab cousins ready to be led into full-scale revolt under a strong leader such as the Mahdi, who represented a local form of Islam that differed from that promoted by the Egyptian religious scholars who had followed the army into Sudan and set up their own government-allied form of Islam.

Zubayr Takes al-Fashir – 1874

In 1883, al-Fashir was a town of only 2650 people, including both Arabs and non-Arab groups such as the Fur, the Zaghawa, the Berti and others. By the time of the siege a year later, it had been ten years since the powerful slaver and freebooter Zubayr Mansur Pasha had roared north to conquer Darfur with an army of loyal Black slave-troops (bazinger-s) from his headquarters in Bahr al-Ghazal. [1]

Zubayr was a Nile Valley Ja’ali of modest background who had worked his way up through the ranks of the slavers busy depopulating parts of southern Sudan in the mid-19th century. He had become wealthy and powerful through his subjugation of the immense southern province of Bahr al-Ghazal before eying the riches of its independent northern neighbor, the sultanate of Darfur. After the defeat and death of Fur sultan Ibrahim Qarad bin Muhammad Husayn in a great battle at Manawashi in 1874, the way was open for Zubayr to enter al-Fashir without a fight on November 2, 1874. The Fur capital was thoroughly looted by Zubayr, who had sworn allegiance to the Egyptian khedive but acted mainly in his own interests. As Zubayr led his army west to conquer neighboring Wadai Sultanate, a weaker detachment of the Egyptian Army entered al-Fashir five days after Zubayr. These troops were led by Governor General Isma’il Ayub Pasha, who claimed Darfur for the growing Egyptian Empire in Africa and confiscated much of the loot Zubayr had left behind in al-Fashir. Isma’il Ayub claimed most of the credit for taking al-Fashir and was duly promoted, while Zubayr found himself cheated out of his anticipated khedive-approved rule of Darfur. Zubayr departed to protest in person in Cairo, where, being judged as overly ambitious and a threat to Egyptian sovereignty in Sudan, he was compelled to remain in comfortable but closely-watched exile. [2]

Opposite the sultan’s al-Fashir palace, Isma’il Ayub ordered the construction of a square fort with a deep trench and bank patrolled by sentries. Inside the fort was a house for the governor and barracks for the troops (Na’um Bey, 1913). A strong zariba (fence made of thorn bushes) surrounded the defenses. A gun at each angle was sufficient to control the town under normal circumstances.

When F Sidney Ensor visited al-Fashir in the late 1870s during an Egyptian government railroad survey, he found the palace occupied by Colonel Alexander Macomb Mason Bey, a Confederate veteran of the Virginia State Navy. Mason was on the staff of the Egyptian khedive after a stint fighting Spain as a mercenary officer in the Chilean Navy. Improvements to the remains of the old palace were made by Egyptian troops to make it suitable for the accommodation of officers, including floors of Norway pine imported at great expense from England.

Slatin and the Loss of Darfur

Rudolf Slatin, a 27-year-old Austrian mercenary in the employ of the Khedive in Sudan, was with the Mahdist army at the time al-Fashir was taken, only seven days after he had surrendered. Slatin, despite only a brief employment by the Austro-Hungarian Army in the Balkans, arrived in Darfur in 1879 and was soon after appointed governor of Darfur in 1881 by Sudan’s governor general, Muhammad Rauf Pasha.

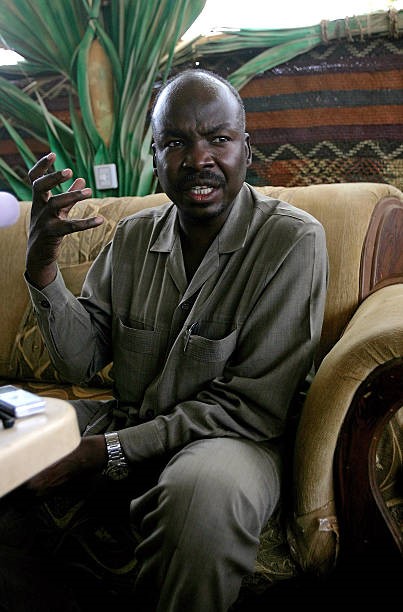

Rudolf Slatin in Mahdist Uniform

Rudolf Slatin in Mahdist Uniform

The young Austrian’s time was almost immediately consumed by military matters, fighting a series of battles, first against the displaced Fur royals, then against the Arabs who had rallied to the Mahdi. In a desperate move, he converted to Islam in 1883 in an unsuccessful attempt to rally his Muslim troops shortly before his surrender at Dara. Thus began Slatin’s 11-year residence in the camp of the Mahdi and his successor, the Khalifa (“successor”). His surrender was marred, however, by his surprising failure to first destroy the Dara garrison’s vast stocks of powder, ammunition and other war materiel that now fell into the eager hands of the Mahdists.

Mahdist Assault on al-Fashir

In early January, 1884, Amir Muhammad Bey Khalid “Zuqal” began marching on al-Fashir, which had already indicated its intention of surrendering after receiving letters from Slatin (now in the Mahdist camp) urging its commander to do so. In anticipation of surrender, the garrison had sent the keys to the treasury to Zuqal by courier and adopted the patched jibba-s (cotton outer garments) worn by the Mahdists. All seemed ready for a peaceful transfer of power; the Egyptian troops were expected to shift their allegiance to the Mahdi.

Zuqal, a Ja’ali Arab from the Nile Valley, had once been one of Slatin’s aides. As a trader and government official, Zuqal was a member of the Bahhara (“those of the river”), the Arab (or Arabo-Nubian) tribes of northern Sudan’s Nile region who had spread as traders throughout Sudan in the wake of the 19th century Turko-Egyptian expansion. A relative of the Mahdi, he was sent by Slatin to Kordofan to appeal to the Mahdi to refrain from raising a rebellion amongst the Arabs in Darfur. Zuqal instead transferred his loyalties to Muhammad Ahmad, being appointed Darfur’s new governor in turn after Slatin’s surrender on December 23, 1883. Many of the smaller Egyptian Army outposts in Darfur soon followed Slatin’s lead, especially after it became known that the Egyptian Army relief expedition led by General William Hicks Pasha (a veteran of the Indian Army) had been utterly destroyed by the Mahdi in Kordofan in November.

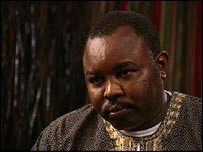

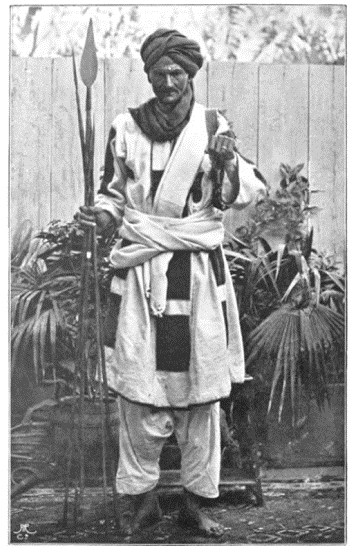

The commander of the Fashir garrison and governor of the city since 1879 was Sa’id Bey Juma’a, a native of Egypt’s Fayyum Oasis. Well known for his “rich vocabulary of bad language,” Sa’id Bey was not always popular with his fellow officers, but was known for his personal courage and devotion to Darfur (Hill,1967, p.325).

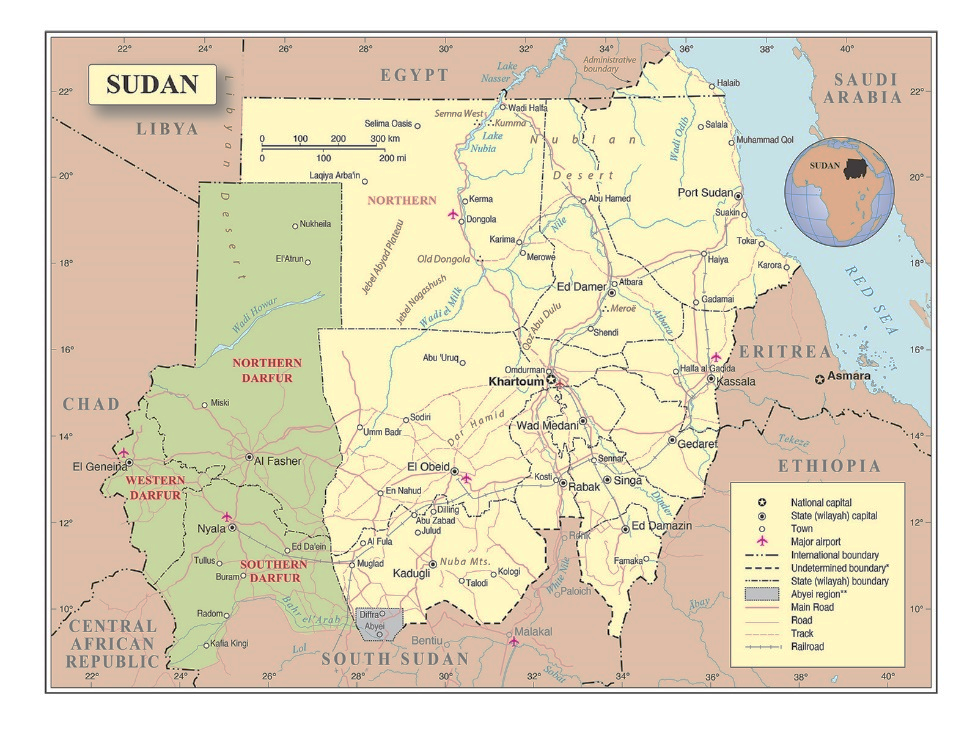

Sa’id Bey Juma’a in Mahdist Uniform

Sa’id Bey Juma’a in Mahdist Uniform

Sa’id Bey was a hard man, but not a stupid man. His small garrison was already weak before the Mahdist siege started. In August 1883, he had dispatched a large force from al-Fashir to clear the surrounding region of insurgents; only 99 men returned. Since then, the Mahdists had only grown in numbers, especially after the defeat of Hicks Pasha and the capture of thousands of Remington rifles. Sa’id Bey and the people of al-Fashir had already decided to submit to the Mahdi, but began to think twice when they heard of the atrocities that had followed the capitulation of Dara, Slatin Bey’s former headquarters (Slatin, p.248).

In the way that the flapping of a butterfly’s wings might be the first breath of a hurricane, one ill-advised admonition changed what was intended to be a peaceful transition of power into a bloody weeks-long confrontation followed by scenes of torture and murder. The courier between al-Fashir and Zuqal’s camp, a local fiki (rural holy man) named Khalifa ‘Abd al-Rahman, full of the religious fervor of the Mahdist revolution and its prohibitions on alcohol and tobacco, piously informed Sa’id Bey Juma’a that he must stop smoking cigarettes.

This was the last straw for Sa’id Bey, who was already alarmed by the brutality dealt out to the officers and leading citizens of Dara and Um Shanga after they had been guaranteed safety. The Bey issued orders for the imprudent fiki to be shot and for his men to discard their Mahdist jibba-s and re-don the uniforms of the Egyptian Army. The fiki somehow escaped his appearance before a firing squad and sent a message to Zuqal regarding Sa’id Bey’s change of heart, no doubt omitting his own role in that reversal. Sa’id Bey now prepared to meet Zuqal’s army with a garrison of 1,000 men, 10 guns and a hand-cranked Gatling gun. The city’s weak point was its wells, the only source of fresh water, which lay just outside the city walls. These could only be used during a siege by teams working under the protection of cover fire from the walls.

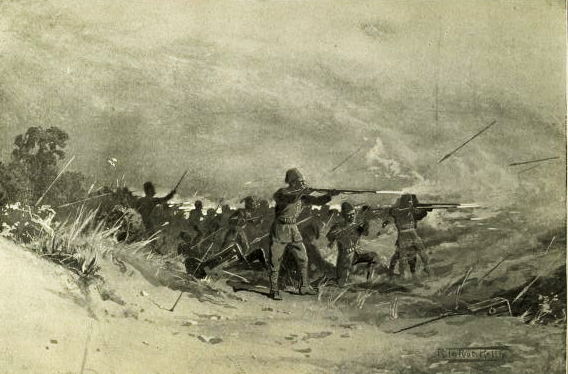

Zuqal launched three assaults on the town, each of which was repelled by the desperate garrison. Sa’id Bey in turn launched several unsuccessful sorties. The Mahdist Amir was compelled to send for reinforcements from Dara and Kabkabiya while recruiting local Arabs to help invest the city. An attempt to bombard the city into submission was made, using artillery captured from other units of the Egyptian Army. This too failed, as the experienced gunners of the Fashir garrison targeted and destroyed the Mahdist guns (Wingate, pp. 130-131).

Death of Hicks Pasha at the Battle of Shaykan

Death of Hicks Pasha at the Battle of Shaykan

Amir Zuqal, who had taken up a position on the site of Sultan Ibrahim’s old palace now ordered his men to fill in the wells just under the city walls, which was carried out under heavy fire from above. The Amir also ordered the captured munitions brought up from Dara that Slatin had failed to destroy before his surrender. As thirst and hunger increased within the walls, Zuqal ordered Slatin (who had also been brought up from Dara for this purpose) to write Sa’id Bey, urging him to capitulate. With the Egyptian Army relief column having already been destroyed by the Mahdi at Shaykan (Kordofan) in November 1883, there was now no alternative to surrender after 15 days of siege. Sa’id Bey would later say that the garrison could have held out at al-Fashir, but for the ammunition stores that Slatin had turned over to the Mahdists (Neufeld, 1899, pp.319-320).

Occupation of al-Fashir

With the city having been so recently looted of its treasures in 1874 by Zubayr and the Egyptian Army (which confiscated some of Zubayr’s loot for transport to Cairo), the Mahdists turned to extreme measures to find wealth they were certain had been hidden by merchants and officers of the Egyptian garrison.

According to Slatin, who witnessed events from the Mahdist camp: “The horrible scenes at Dara were now re-enacted with even greater severity, and numbers of people were tortured in the most merciless manner” (Slatin, p. 149). Egyptian officers were targeted especially; Major Hamada Effendi was flogged daily for three days in an unsuccessful attempt to make him reveal where his money was hidden; after the flogging ceased each day, a mixture of salt-water and hot peppers was poured over his ragged flesh. Called a slave by one of his captors, another officer, Ibrahim Tagalawi, shot his wife, his brother and himself; Sa’id Agha Fula committed suicide rather than undergo the disgrace of flogging. The Mahdi’s army had need of professional soldiers, so Zuqal eventually ordered a halt to the floggings and beatings of the officers. Sa’id Bey Juma’a, the bristly nicotine-deprived governor, escaped death only through the intervention of Slatin and, after a term of imprisonment, became chief of the Mahdist artillery in the siege of Khartoum. Slatin became a closely-watched bodyguard and advisor to the Mahdi’s successor, Khalifa ‘Abd Allahi al-Ta’aisha, before escaping from Omdurman in 1895.

Only days after the fall of al-Fashir, Slatin received a letter containing orders he could no longer carry out as a prisoner of the Mahdi. Khartoum had instructed him to concentrate all his men and supplies at al-Fashir and there await the arrival of Fur “sultan” ‘Abd al-Shakur ibn ‘Abd al-Rahman Shattut, who would restore Fur rule in al-Fashir under Egyptian sovereignty. That was Governor General Gordon’s plan. In reality, ‘Abd al-Shakur, who had been plucked from the Fur royal exiles living in Cairo since 1874, made only a sluggish, alcohol-fogged procession up the Nile, failing to get much further than Dongola. Gordon pulled the plug on the whole operation and ‘Abd al-Shakur returned to the safety of obscurity.

Conqueror of al-Fashir

Zuqal crowned his conquest of the Fur capital by marrying the Iya Basi (Fur – “great sister”), a traditional pre-Islamic position in the Fur royal hierarchy assumed by a full sister of the sultan. The Iya Basi maintained her own palace, wealth and retinue of hundreds of slaves and servants. Now comfortably ensconced in al-Fashir, Zuqal began the dangerous practice of ignoring summonses from the Mahdi to join his forces in Kordofan.

At the time of the siege, Sultan Harun Dud Banga was in the ancestral Fur homeland, the mountains of Jabal Marra, where he had been fighting a guerrilla campaign against the Turko-Egyptians. With the Egyptian Army no longer a threat after their collapse in Darfur, the sultan was faced with a new and more dangerous enemy – the Mahdists, with their core of Arab tribesmen who had resisted Fur rule for many years. Zuqal assembled an army of captured Sudanese regulars who had served in the Egyptian Army and Black slave troops (bazinger-s), supplemented by as many as 20,000 Arabs. The Mahdist army marched into the hills of Jabal Marra, where they cornered Sultan Harun in a hill-top stronghold. The Mahdists suffered enormous losses storming the fortress, but eventually broke resistance after a two-month siege. Harun was enlisted in the Mahdi’s army and reported to have met his death a few years later fighting the Abyssinians at Gallabat in 1889, though another account claims he survived the Mahdiya and lived quietly at al-Qadarif in eastern Sudan until 1903. [3]

The Mahdi died soon after the conquest of Khartoum and the death of hir rival Gordon, but Zuqal remained at al-Fashir until March 1886, when he finally responded to a series of letters from the Khalifa ‘Abd Allahi summoning him to Omdurman. The main obstacle to ‘Abd Allahi’s efforts to consolidate his power as the Mahdi’s successor came from the Mahdi’s Nile Valley Arab relatives, the Ashraf; Zuqal, as a relative of the Mahdi, was now under suspicion. His departure for Omdurman with a large armed following only alarmed the Khalifa, who ordered Hamdan Abu ‘Anja to intercept Zuqal’s party. Zuqal quickly found himself under arrest at al-‘Ubayd in Kordofan, relieved of his soldiers and his wealth (Wingate, pp.291-292).

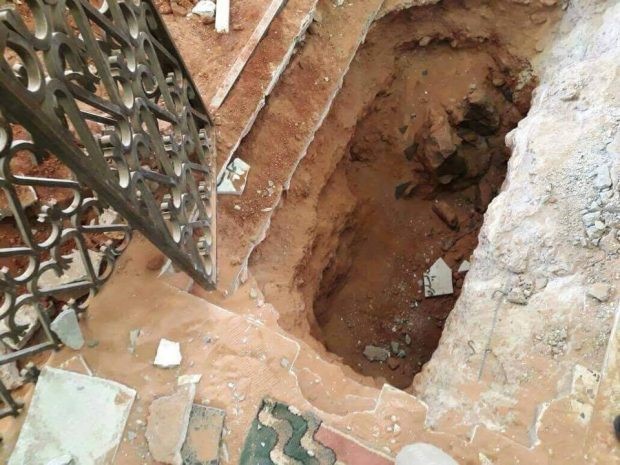

After the Ashraf ceased to be a threat to ‘Abd Allahi’s power, Zuqal found his way back into the Khalifa’s good graces and back out again. He was eventually exiled to Rajaf in southern Sudan but freed by Belgian forces in 1897. [4] He returned to Darfur only to be executed by ‘Ali Dinar, who had restored the Fur Sultanate in the days after the Battle of Omdurman (1898). Zuqal was taken into the hills of Jabal Marra, where he was “lowered into a well containing the bones of many former offenders, the rope cut, and left to die, with a guard posted to ensure no assistance” (Egyptian Army Military Intelligence Summary, 1902).

Aftermath

Many of the Black soldiers who served under Slatin before being absorbed into the Mahdist ranks mutinied in al-‘Ubayd in October 1885. Most of these troops came from the Nuba Hills of South Kordofan, and it was to that place that they marched, still in order and under arms. Such defiance could not be condoned by the Khalifa, and Mahdist troops spent months exterminating the mutineers in the hills.

Egyptian Troops in Action in Sudan, 1879

Egyptian Troops in Action in Sudan, 1879

Sa’id Bey died in his home oasis of Fayyum in 1912, having sought a quiet life there since his experiences in the Mahdiya.

When Sultan ‘Ali Dinar revived the Fur Sultanate in 1898, he began repairing the damage and neglect of the city by ordering the construction of a vast new palace compound (hosh) and mosque, as well as a qubba-style (beehive-shaped) memorial to his father, Zakariya. Despite the ever-present risk of a raid by the restless Arab Baqqara (especially the Rizayqat of Musa Madibbo), al-Fashir grew in importance and prosperity under Sultan ‘Ali Dinar until 1916, when it was occupied once more by the Egyptian Army, this time under British leadership and direction.

Notes

- Egyptian ranks and titles used in this paper include Agha, Bey, Effendi, Khedive and Pasha. All were part of the Turkish nomenclature for political and military titles, Turkish still being the working language of the Egyptian Army in the 19th Definitions below (with the exception of khedive) are those relevant to military usage.

Agha: An honorific for officers below the rank of Kaimakam (roughly ‘colonel’), it also tended to indicate the officer was non-literate.

Bey: An honorific for senior officers below the level of Pasha, available in several grades.

Effendi: Like Agha, an honorific for officers below the rank of Kaimakam, but implying literacy and education.

Khedive: “Viceroy,” i.e. of the Ottoman sultan. Originally from the Persian khediv. Though first used by Muhammad ‘Ali in 1805, its use was only recognized officially by the Ottoman sultan from 1867 to 1914.

Pasha: Another Turkish term with Persian origins, Pasha was the highest title, available in four grades for military officers.

- For the consequent collusion between Zubayr in Cairo and his ill-fated son Sulayman in Bahr al-Ghazal, see: “Romolo Gessi Pasha: Early Counter-Insurgency Lessons from an Italian Soldier of Fortune’s Campaign in Central Africa,” Military History Online/AIS, August 21, 2016, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3696

- For Gallabat, see Hill (1967), p.4 and Wingate (1891), p.325; for al-Qadarif, see Sudan Archives Durham SAD 731/6/68 and HHS Morant: “Recent History of Darfur” (Sudan Military Intelligence Report no.104).

- Rajaf, a town in Central Equatoria (now part of the state of South Sudan), was near the southernmost extent of the Mahdist state and used as a place of exile for those who offended the Khalifa. The Mahdists were expelled from the town in February 1897 by Congo Free State forces led by Louis-Napoléon Chaltin, a veteran of the 1882-1884 Congo Free State war with Zanzibari Arab merchants and slavers.

Bibliography

Egyptian Army Military Intelligence Summary (MIS) no. 93, April 1902, Sudan Archives Durham, SAD 735/3/1-27.

Ensor, F. Sidney: Incidents on a Journey through Nubia to Darfoor, WH Allen, London, 1881.

Farwell, Byron: Prisoners of the Mahdi, Harper and Row, New York, 1967.

Haim Shaked: The Life of the Sudanese Mahdi: A Historical Study of Kitab sa’adat al-mustahdi bi-sirat al-Imam al-Mahdi by Isma’il b. ‘Abd al-Qadir, Transaction Books, New Brunswick N.J., 1978.

Hill, Richard: A Biographical Dictionary of the Sudan, 2nd Ed., Frank Cass & Co., London, 1967.

Holt, PM: The Mahdist State in the Sudan, 1881-1898: A study of its origins, development and overthrow, (2nd ed.), Oxford, 1970.

Lampen, GD: “History of Darfur,” Sudan Notes and Records 31(2), 1950, pp. 177-209.

Mamdani, Mahmood: Saviors and Survivors: Darfur, Politics, and the War on Terror, Pantheon Books, New York, 2009.

McGregor, Andrew: “American Civil War Veterans and the Egyptian Empire in Africa,” A lecture given at the Royal Canadian Military Institute, Toronto, March 28, 2018, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4264

Na’um Bey Shuqair: “The Masalit and Tama Sultanates: Are they within Darfur or Wadai Sultanate,” Typescript, February 2, 1913, Sudan Archives Durham, SAD 731/6/109.

Neufeld, Charles: A Prisoner of the Khaleefa. Twelve Years Captivity at Omdurman, Chapman & Hall, Ltd., London, 1899.

Report on the Egyptian Provinces of the Sûdan, Red Sea, and Equator, Intelligence Branch, Horse Guards, War Office, HM Stationary Office, London, 1883.

Slatin Pasha, Colonel Sir Rudolf: Fire and Sword in the Sudan: A Personal Narrative of Fighting and Serving the Dervishes, 1879-1895, Edwin Arnold, London, 1897.

Theobald, AB: The Mahdiya: A History of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1881-1899, Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1951.

Wingate, Major FR: Mahdiism and the Egyptian Sudan, MacMillan and Co., London, 1891.