Andrew McGregor

November 30, 2012

The seizure last week by mutinous Congolese soldiers of the city of Goma in the midst of the mineral rich Kivu province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has brought the deaths of hundreds of people and displaced hundreds of thousands of others. The ineffective response of the DRC military and the UN troops intended to support it has nourished fears that the mutineers might continue their march through the Congo, plunging the war-wracked state into yet another round of uncontrollable violence.

Now calling itself the Revolutionary Army of the Congo (RAC), the group of mutineers formerly known as M23 had pledged to march on the DRC capital of Kinshasha if DRC president Joseph Kabila failed to agree to discuss their demands, which include calls for national talks to be hosted by President Kabila, the release of political prisoners (including leading opposition politician Etienne Tshisekedi), the dissolution of the national electoral commission (believed by the ARC to have arranged Kabila’s re-election in 2011) and the investigation of military corruption (New Vision [Kampala], November 27, 2012).

Now calling itself the Revolutionary Army of the Congo (RAC), the group of mutineers formerly known as M23 had pledged to march on the DRC capital of Kinshasha if DRC president Joseph Kabila failed to agree to discuss their demands, which include calls for national talks to be hosted by President Kabila, the release of political prisoners (including leading opposition politician Etienne Tshisekedi), the dissolution of the national electoral commission (believed by the ARC to have arranged Kabila’s re-election in 2011) and the investigation of military corruption (New Vision [Kampala], November 27, 2012).

The RAC/M23 movement has its origins in the largely Tutsi Congrès national pour la défense du peuple (CNDP), an ethnic-defense militia based in the DRC province of Nord-Kivu. [1] The movement was believed to have been sponsored by Rwanda as a proxy force for use against the Kivu-based Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda (FDLR), a Hutu militia determined to finish the genocide of Tutsis and moderate Hutus that ravaged Rwanda in 1994. The FDLR appears to have stepped up cross-border operations into Rwanda in recent days and has renewed clashes with RAC/M23 (AP, November 27, 2012). The ICC issued a warrant in July for the arrest of FDLR commander Sylvestre Mudacumura, a Rwandan Hutu facing nine counts of war crimes.

General Bosco “The Terminator” Ntaganda, a Rwandan Tutsi wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes committed while both a rebel and an officer in the DRC national army, took control of the CNDP in 2009. [2] The peace agreement that followed in that same year resulted in the integration of most of the CNDP into the DRC army, known as the Forces armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC). Colonel Ntaganda led a mutiny of up to 600 soldiers in Nord-Kivu in March after orders came for the ex-CNDP troops to be redeployed from Kivu, where ex-members of the CNDP had made a comfortable living by exploiting and taxing the numerous mining operations in the area. The Mouvement du 23 Mars (M23) was named for the March 23, 2009 peace agreement that movement leaders claim Kinshasha failed to honor (East African [Nairobi], July 16, 2012).

Colonel Ntaganda, who has always denied being the M23 commander despite abundant evidence to the contrary, has kept a low profile since April, allowing the movement’s leadership to pass into the hands of its official commander, Colonel Sultani Makenga. Makenga (now a RAC brigadier) is a former CNDP commander who is believed to have played a major role in massacres carried out in the region in 2007 and 2008. Colonel Makenga denies Ntaganda is being harbored by the RAC (East African [Nairobi], October 22, 2012). At the time of his desertion from FARDC in May, Colonel Makenga was the second-in-command of DRC operations against the Hutu FDLR. Makenga was designated for asset seizure by the U.S. Treasury Department on November 13 in relation to his alleged use of child soldiers and being a recipient of arms and material related to military activities in the DRC.

Under a deal forged by Uganda, a RAC spokesman announced on November 29 that the movement would hand over the town of Sake to UN forces on November 30, to be followed by a withdrawal from Goma to a point 12 miles north of the city, though 100 RAC fighters would be allowed to remain at the Goma airport (AFP, November 29, 2012). In return, Kinshasha has agreed to negotiate with the rebels and hear their grievances, once they have retreated to 20 kilometers (12 miles) north of the city.

The Assault on Goma

A three-month truce was shattered on November 15 as RAC and Congolese forces clashed at daybreak, both sides claiming later to have acted in self-defense. Tanks belonging to the UN’s Mission de l’Organisation des Nations Unies en République Démocratique du Congo (MONUSCO) rolled into defensive positions outside Goma, ready to support the defense of the city of one million people close to the Rwandan border. On November 18, UN attack helicopters, provided by the Ukraine and operated by Ukrainian pilots ran ten strike missions against the rebels outside Goma (AFP, November 18, 2012). The night before the assault on Goma, Rwandan General Joseph Nzabamwita reported that the DRC army had bombarded the Rwandan border region with T-55 tank shells, mortars and anti-aircraft missiles. A FARDC spokesman said an investigation was under way but countered that Rwanda had also fired mortars across the border (AFP, November 19, 2012).

Patrol of the Revolutionary Army of the Congo near Goma

Patrol of the Revolutionary Army of the Congo near Goma

RAC forces continued to advance and took the city in the morning of November 20 after a few hours of light resistance from FARDC and UN forces based in Goma. With the RAC on the outskirts of Goma, DRC forces engaged in some tough talk, with the local Republican Guard commander promising to “die with the population” rather than leave them to the hands of the rebels (Agence Congolaise de Presse, November 19, 2012). Residents of Goma reported that the Republican Guard (which reports to the president directly rather than to FARDC command) did offer some resistance to the insurgents while FARDC troops busied themselves with looting before abandoning the city (AFP, November 19, 2012). A FARDC spokesman claimed later that DRC armor came under fire from Rwandan artillery every time they tried to shell RAC positions, but a Rwandan spokesman replied: “Every time [FARDC] gets beaten on the ground, they use the RDF [Rwandan Defense Force] as an excuse” (AFP, November 17, 2012). Many of the Congolese troops shed their uniforms before fleeing into the bush. The precipitate departure of Congolese forces from Goma appears to have provided the ARC with an arms windfall of as much as 1,000 tons of arms and ammunition, including heavy artillery (AP, November 27, 2012).

After the attack, the DRC government reported that the rebels had been reinforced by 4,000 Rwandan troops and had been provided with night-vision goggles that gave them an advantage in the fighting (Agence Congolaise de Presse, November 19, 2012; November 20, 2012). The DRC had earlier claimed to have found bodies wearing Rwandan Army uniforms after clashes with the RAC on November 15, but a Rwandan army spokesman retorted: “This an old propaganda gimmick; it’s easy to try to draw Rwanda into this mess” (AFP, November 15, 2012; November 18, 2012, Jeune Afrique, November 17, 2012).

French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius expressed his disappointment with the performance of the UN’s 1,500 man peacekeeping force in Goma: “MONUSCO’s mandate should be revised. MONUSCO was not in a situation where it could prevent what happened when faced with a few hundred men” (AFP, November 20, 2012). The UN has stated its Goma contingent, part of a force of 6,700 UN troops in Nord-Kivu, would remain in Goma, though their role in the current situation remains undefined.

UN peacekeeping chief Herve Ladsous defended the MONUSCO contingent in Goma, pointing out that their mandate called for support of FARDC troops, but given the fact that government forces fled from Goma shortly after fighting began this was “hardly achievable… and clearly it is not the role – not the mandate of MONUSCO – to directly hit the armed groups…” (Xinhua, November 21, 2012).

MONUSCO’s ineffective defense of Goma sparked large demonstrations in several cities, including Kisangani, where UN vehicles were set on fire and stones thrown at UN offices. Protesters also targeted the government and the ARC for their roles in the continuing violence (Agence Congolaise de Presse, November 21, 2012; November 22, 2012).

After a “strategic withdrawal” from the Goma area, FARDC troops are now based around the town of Minova, 36 miles from Goma. On November 22, FARDC launched an offensive to retake the town of Sake, west of Goma. The Goma Airport remains under the control of UN forces.

Regional Involvement in the Crisis – Rwanda

A UN report on foreign military involvement in the Kivu region was leaked earlier this month, creating a diplomatic crisis in the Great Lakes region. Much of the report appeared to confirm the DRC’s claims that neighboring Rwanda and Uganda were providing arms, intelligence and logistical support to RAC/M23. The DRC is now demanding that Rwanda and Uganda be targeted by U.S. and UN sanctions for its support of RAC (AFP, November 18, 2012). Some of the fallout was internal, however; General Gabriel Amisi Kumba, the chief of DRC land forces, was dismissed by President Kabila on November 22 after having been accused in the report of trafficking arms to various militant groups, including suspected RAC allies in the local Maï-Maï and anti-Hutu Raia Mutomboki groups (JournaldeKin.com [Kinshasha], November 23, 2012; AFP, November 22, 2012).

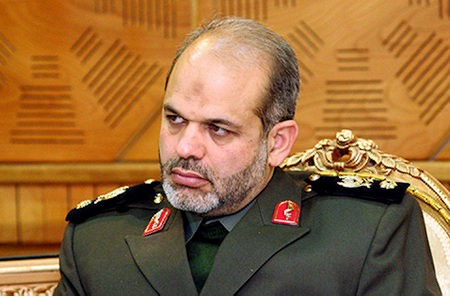

Based partly on MONUSCO radio intercepts, Rwanda was identified in the report as playing a major role in creating and backing RAC/M23, with Minister of Defense General James Kabarebe accused of directing the movement’s activities with the assistance of Army chief-of-staff Lieutenant General Charles Kayonga and Lieutenant General Jacques Nziza. Rwandan troops fought in the Congo during the rebellion against President Mobutu Sese Seko in 1996-1998 and again from 1998 to 2003. Rwandan troops returned to the DRC with permission in 2009 to pursue the Hutu FDLR militia.

Rwanda’s activities in the border region have led to the cancelling of an important training agreement with the Belgian military; according to Belgian foreign minister Didier Reynders: “We will not train soldiers who could contribute to the destabilization [of the Congo]” (Radio Télévision Belge Francophone, November 11, 2012). The DRC, seeing an opportunity, dispatched Prime Minister Augustin Matata Ponyo to Brussels to urge greater military assistance and training from the Belgians.

Regional Involvement in the Crisis – Uganda

Uganda, which President Kabila describes as “the bad boy” of the region, was also identified as a major backer of RAC/M23, much to the outrage of Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni (Sunday Monitor [Kampala], October 29, 2012). Ugandan police chief Lieutenant General Kale Kayihura and the President’s brother, General Salim Saleh, were singled out in the UN report for providing military assistance and troops to RAC/M23 (Daily Monitor [Kampala], November 5, 2012).

Uganda has intervened in the DRC before, particularly in 1996-1998, when Ugandan troops backed Laurent Kabila’s efforts to depose President Mobutu Sese Seko and again in 1998-2003 during a vast civil war that dragged in many other African countries. Ugandan generals, some related to President Museveni, made enormous profits by pillaging the eastern Congo’s mineral industry.

Ugandan premier Amama Mbabazi described the leaked report as the work of “UN amateurs” and asked:

Why should we continue involving Uganda where the only reward we get is malignment? Why should the children of Ugandans die and we get malignment as a reward? Why should we invite retaliation by [Somalia’s] al-Shabaab by standing with the people of Somalia, only to get malignment by the UN system? (Daily Monitor [Kampala], November 2, 2012).

After the release of the UN report, Uganda announced it was considering three options before taking action:

- Withdrawing from regional peacekeeping operations in Somalia (where they form the core of the African Union Mission in Somalia – AMISOM) and the Central African Republic

- Continuing with these operations despite the UN report

- Demanding a withdrawal of the allegations contained in the UN report before allowing Ugandan peacekeeping operations to continue (Daily Monitor [Uganda], November 26, 2012).

After Uganda made its threat to abandon UN-backed peacekeeping operations in Somalia, UN officials quickly began to back away from the report, saying that the views expressed therein “did not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations” (Africa Review [Nairobi], November 5, 2012).

During an interview with a local newspaper, Ugandan defense minister Dr. Crispus Kiyonga admitted that Ugandan authorities had conducted secret meetings with RAC/M23 to urge them to stop fighting and suggested that these meetings might have been misinterpreted as support for the group (Daily Monitor [Kampala], November 12, 2012).

Pursuit of the largely moribund Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) rebel group is often cited by the government as the reason for its cross-border military operations in the eastern DRC. Museveni claims that a recent series of assassinations of prominent Muslim clerics in Uganda is the work of ADF operatives based in the DRC (Observer [Kampala], September 17; for the ADF, see Terrorism Monitor, December 20, 2007). In an interview with Ugandan journalists, Kabila said joint DRC-Ugandan operations against elements of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) based in the Congo had been successful and that further joint operations against Ugandan rebels of the ADF based in the Kivu region would have followed if they hadn’t been pre-empted by the new outbreak of violence in the region (Sunday Monitor [Kampala], October 29, 2012).

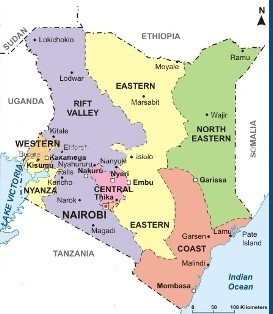

As leader of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR), President Museveni is officially leading regional efforts to quell the fighting in Kivu and appears to have some influence over RAC/M23. [3] Despite the claims that Uganda is arming and facilitating the RAC/M23 rebellion, Uganda says it still has the “moral authority” to continue as a mediator in the conflict (IRIN [Nairobi], November 23, 2012). The ICGLR has proposed forming a “neutral” international force of 4,000 troops under AU and UN supervision to eliminate armed groups in the eastern DRC, but it will be difficult to find solid commitments of trained and capable troops for this force. The neutral force is intended to include 4,000 troops from Angola, Tanzania, Kenya and the DRC, although only Tanzania has committed a small force of 500 men in the three months that have passed since the creation of the force was announced, and funding remains unconfirmed. It was intended to deploy the force by December, but this now appears unlikely (Daily Monitor [Kampala], November 1, 2012). DRC Prime Minister Ponyo has stated his preference for a “reinvigorated” MONUSCO as a “credible and realistic alternative” to the proposed “neutral international force” (Agence Congolaise de Presse, October 26, 2012). President Museveni, who favors the new force, has said that what is required is a “new hybrid of troops who are ideologically committed and loyal” (Observer [Kampala], September 17, 2012).

Conclusion

The struggle for the wealth of Kivu Province continues without regard for the residents of the region, who are buffeted one way or another by offensives and counteroffensives. For now, however, it appears that RAC has stepped back from its announced intention of taking the war to Kinshasha, which was always more of a threat than a potential reality due to the great distances, difficult terrain and hostile groups that would be encountered on any march to the national capital. If the RAC actually withdraws from Goma in the coming days (which is by no means guaranteed), it has still emerged from the latest round of fighting with greater wealth, more arms and a degree of respect for their military capabilities when matched with FARDC. The question is whether RAC can translate their new situation into an agreement by a largely unwilling DRC government to consider or even discuss their demands. For the moment, FARDC, even with the support of UN forces, is almost certainly incapable of driving RAC from its lucrative bases in the mining regions of Nord-Kivu and Sud-Kivu. The region’s notorious volatility and reputation as a haven for every type of bandit and would-be revolutionary does not hold much promise that a truce with one group will prevent other groups from continuing to rampage across the eastern Congo. In the end, Rwanda, Uganda and the DRC all value their proxy militias too much to be expected to take decisive steps to bring peace to a region bearing impressive mineral wealth for those willing to bend international protocols to exploit it.

Notes

1. For background on the M23, see Andrew McGregor, “M23: A New Player in the Proxy Wars of the Democratic Republic of the Congo,” Terrorism Monitor, July 26, 2012.

2. For Ntaganda, see Andrew McGregor, “War Crimes, Gold Mines and Mutiny in the North-East Congo: A Profile of General Bosco Ntaganda,” Militant Leadership Monitor, August 31, 2012,

3. The ICGLR consists of 11 member-states: Angola, Burundi, Central African Republic, Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania and Zambia.

This article was originally published in the Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor