Andrew McGregor

Terrorism Monitor 21(24)

Jamestown Foundation, Washington DC

December 15, 2023

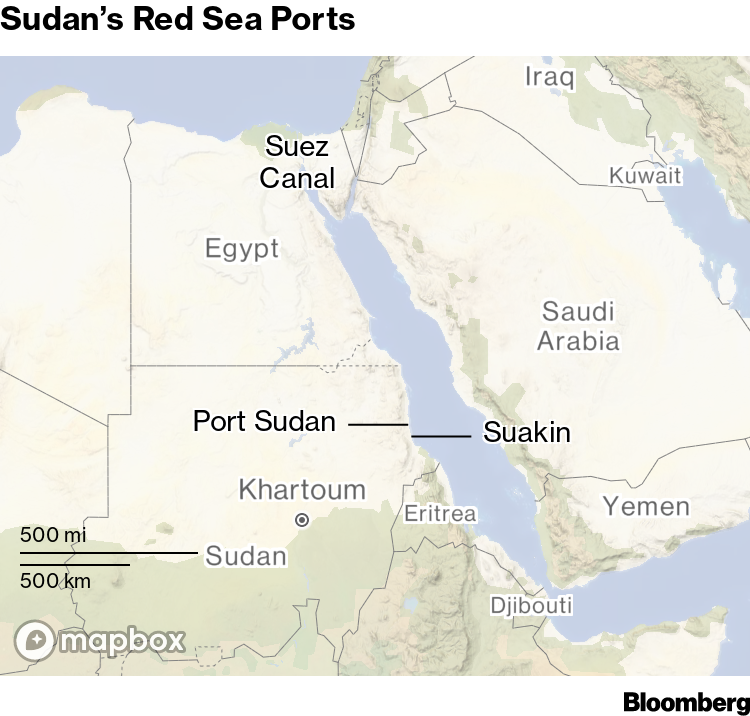

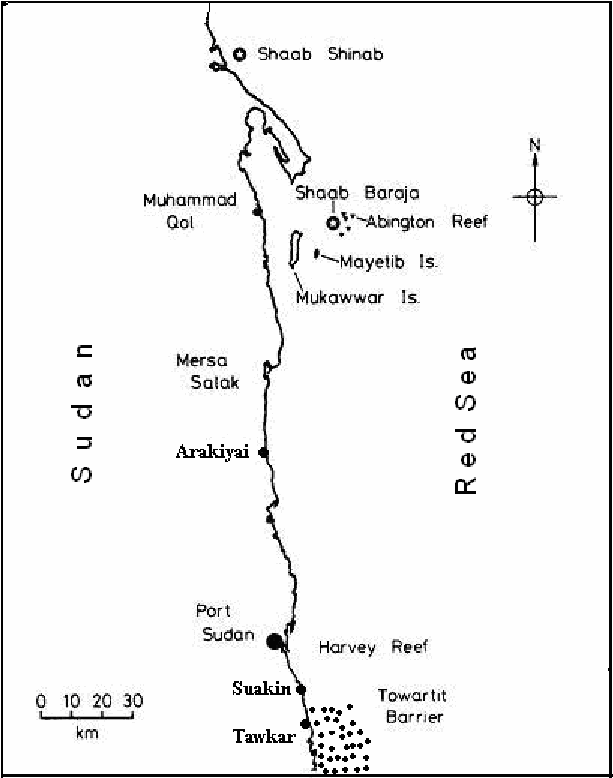

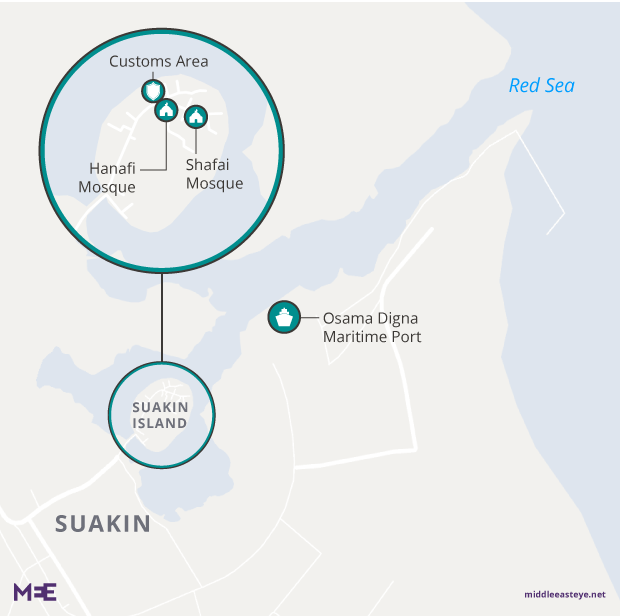

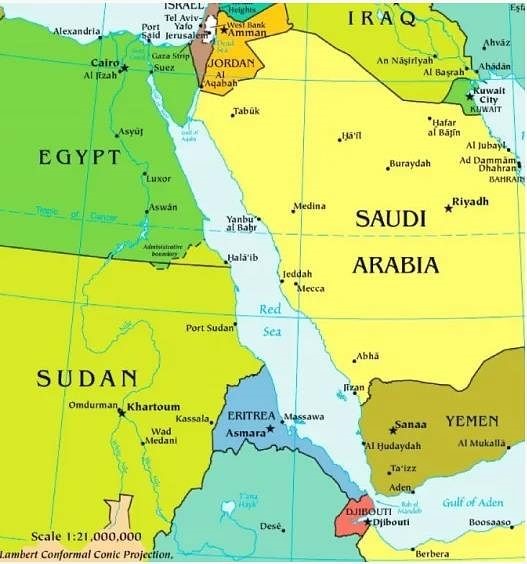

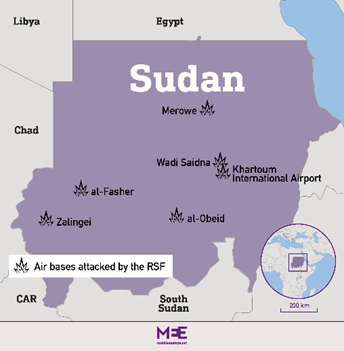

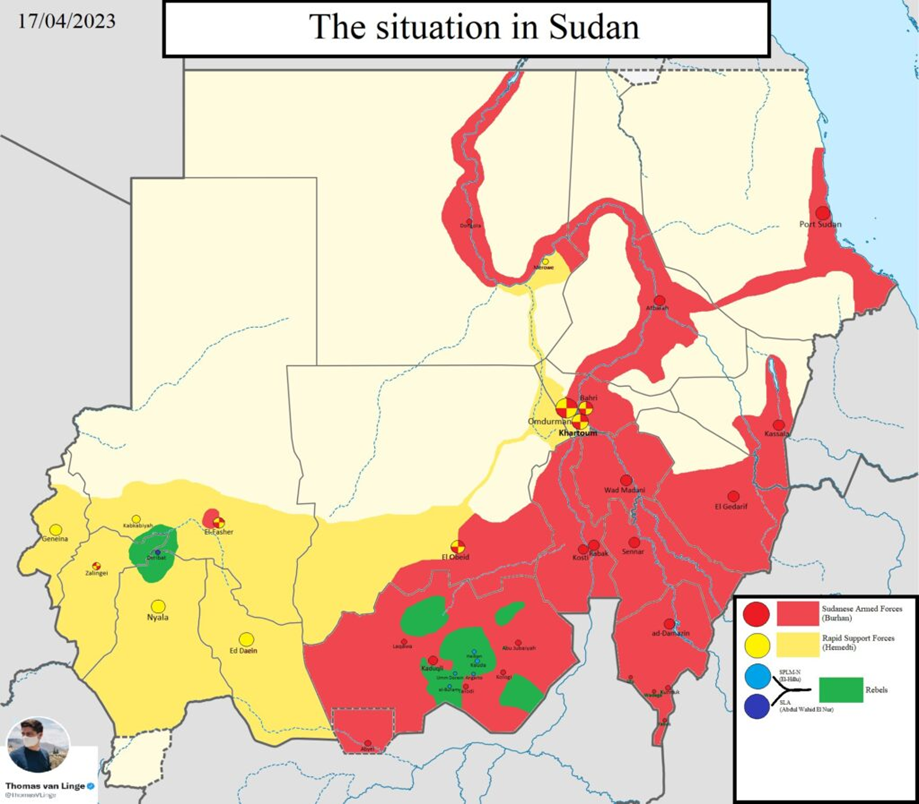

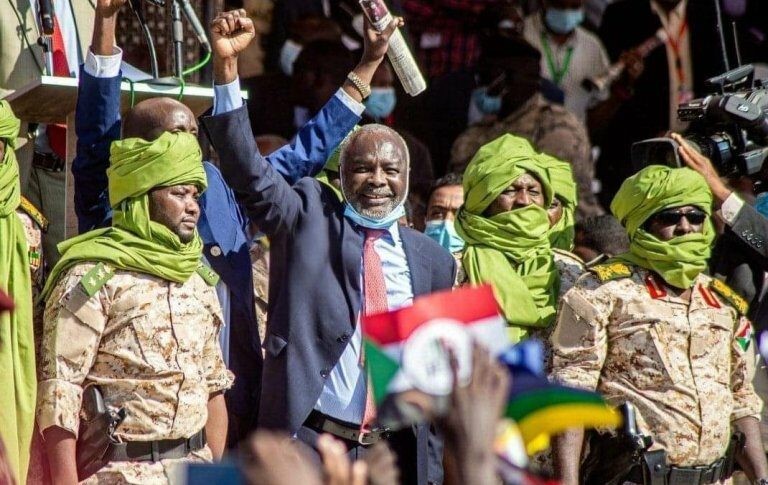

After eight months of brutal warfare, Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) now appear to have the upper hand against the better-armed Sudan Armed Forces (SAF). Led by Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti,” the RSF has conducted a highly mobile campaign against the SAF’s reactive and defensive posture, allowing the group to take the initiative in all regions of the conflict. With the Sudanese capital of Khartoum now a devastated battlefield, the ineffective government, led by SAF commander-in-chief General Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan, operates from a temporary base in Port Sudan, which suffers from power shortages and a chronic lack of fresh water.

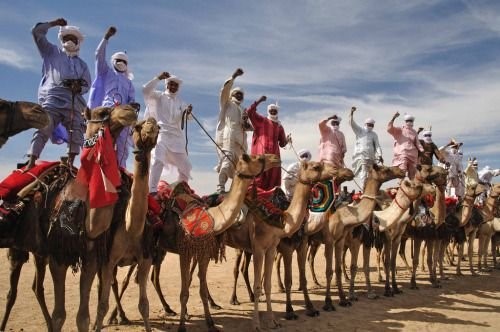

Peace talks in Jeddah between the two military factions, assisted by Saudi, American, and African Union mediators, were indefinitely suspended earlier this month after both sides failed to meet commitments agreed upon in earlier negotiations (al-Taghyeer [Khartoum], December 4; Africa News, December 5). The animosity between the factions is severe and historically based in the rivalry between the poor Arab tribesmen of western Sudan (the RSF) and the Arab elites of the Nile region who have controlled Sudan and its military since the country gained independence in 1956.

Peace talks in Jeddah between the two military factions, assisted by Saudi, American, and African Union mediators, were indefinitely suspended earlier this month after both sides failed to meet commitments agreed upon in earlier negotiations (al-Taghyeer [Khartoum], December 4; Africa News, December 5). The animosity between the factions is severe and historically based in the rivalry between the poor Arab tribesmen of western Sudan (the RSF) and the Arab elites of the Nile region who have controlled Sudan and its military since the country gained independence in 1956.

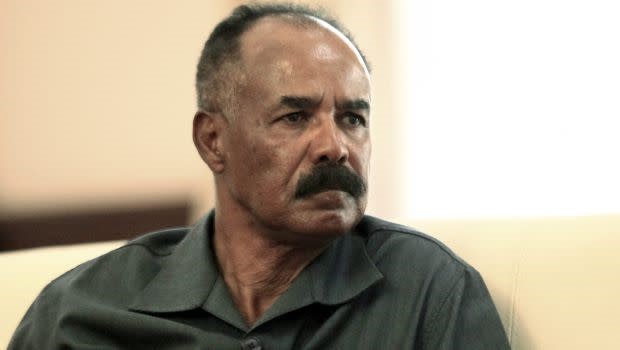

RSF Commander General Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti”

RSF Commander General Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti”

Resistance to the RSF onslaught is weakening at all levels, placing Sudan’s diverse population at risk of rule by Arab supremacists with a record of savage conduct and a general ignorance of the means of development, administrative techniques, economic theory, and international relations.

The Impending RSF Conquest of Darfur

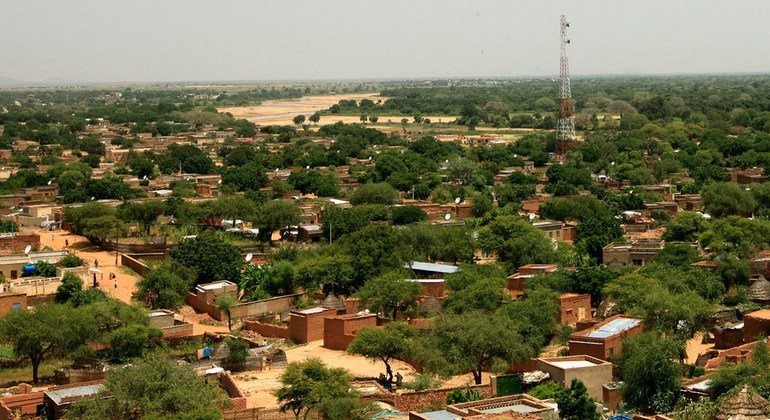

Four of Darfur’s five states, comprising nearly 80 percent of the western province, are now in RSF hands. North Darfur state and its capital, al-Fashir, may be the RSF’s next target. Al-Fashir is strategically and symbolically important as the former capital of the once powerful Fur Sultanate (c.1650-1916). Security in North Darfur is provided largely by the Joint Protection Force (JPF), an alliance of five non-Arab armed movements that has been busy recruiting in the region in anticipation of an RSF offensive. The RSF has also been recruiting from the region’s Arab population, setting the stage for a vicious ethnic conflict that will inevitably result in the mass slaughter and displacement of many of North Darfur’s civilians. Convoys bringing supplies to North Darfur from central Sudan have stopped, creating shortages of food, fuel, and medicines (Sudan Tribune, December 7).

JEM Leader Jibril Ibrahim (Sudan Tribune)

JEM Leader Jibril Ibrahim (Sudan Tribune)

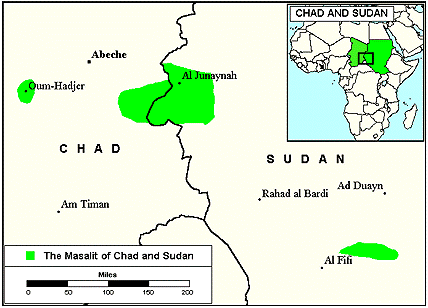

Two major armed movements, the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) and the Sudan Liberation Army of Minni Minawi (SLA-MM), abandoned their self-declared neutrality on November 16 to announce their support for the SAF. Both groups also declared their willingness “to participate in military operations on all fronts without hesitation” (Radio Dabanga, November 17). JEM leader Jibril Ibrahim also condemned the RSF’s use of Arab mercenaries from Chad and Niger who have been promised the right to settle on land cleared of its non-Arab residents. The declaration followed months of murder and rape inflicted by the RSF on the non-Arab Black population of Darfur. The most notable atrocity involved the murder of some 1,300 civilians (mostly Masalit, an ethnic group in western Sudan and eastern Chad) in a camp for displaced people in West Darfur. The RSF attack began on November 2 and only ended three days later (Al Jazeera, November 10). The non-Arab Masalit have been targeted by the RSF and Arab militias since the start of the war in what appears to be an effort to ethnically cleanse the region of its indigenous Black population (see Terrorism Monitor, June 26).

Despite their small numbers, the ambitious Black African Zaghawa ethnic group plays a leading role in Darfur’s anti-government opposition. SLA-MM leader Minni Minawi, JEM leader Jibril Ibrahim, and al-Tahir Hajar, leader of the Gathering of Sudan Liberation Forces (GSLF), are all Zaghawa. During the fighting for Nyala, RSF gunmen were accused of assassinating prominent members of the Zaghawa community (Sudan Tribune, September 16).

Darfur Governor and SLA-MM Leader Minni Minawi (AFP)

Darfur Governor and SLA-MM Leader Minni Minawi (AFP)

Minni Minawi, governor of Darfur since August 2021, remains wary of the SAF, which continues to be commanded by members of Sudan’s riverine Arab elite. The rank-and-file troops are composed of conscripts from other regions, including many non-Arabs. Without substantial reforms to the composition of the SAF, Minawi notes its victory might only mean a return to an oppressive status quo (Sudan War Monitor, December 4).

RSF’s Series of Conquests

Under pressure from the RSF, garrisons across Darfur have fallen like dominos. Nyala, Sudan’s second-largest city, is the capital of South Darfur and an important military strongpoint. It fell after a long siege followed by a four-day assault that ended on October 26, killing hundreds of civilians during the shelling of the city (Asharq al-Awsat, October 29).

Zalingei, the capital of Central Darfur, was lost after the SAF’s 21st Infantry Division fled on October 31, allowing the RSF to walk in. Al-Geneina, capital of West Darfur, was taken by the RSF on November 4 after most of the 15th Division garrison fled, leaving hundreds of troops and weapons behind. Masalit civilians and captured troops were abused, whipped, and forced to run barefoot through the rubble (Sudan War Monitor, November 6). Gathering smaller garrisons along the way, the remaining defenders fled to Chad, where they were disarmed and interned. Elsewhere in South Darfur, officers have changed into civilian clothes and made for the border with South Sudan (Sudan War Monitor, November 27).

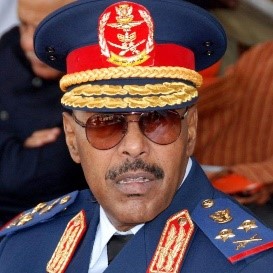

SAF Leader General al-Burhan (BBC)

SAF Leader General al-Burhan (BBC)

As it consolidates control of Darfur, the RSF is now poised to begin operations against al-Ubayd, the capital of neighboring North Kordofan. The RSF has already driven away the SAF’s garrison in the western Kordofan town of al-Mojalid and the nearby Balila oilfield (a joint Sudanese-Chinese project), despite intensive airstrikes by the SAF (Asharq al-Awsat, October 31; al-Taghayeer [Khartoum], November 27).

Where Do Armed Opposition Movements Stand?

The war of the generals has finally shattered the hard-won 2020 Juba Peace Agreement (JPA), which promised a new era of peace in Sudan by reconciling the government with the nation’s leading rebel movements. However, two of the most powerful movements rejected the process entirely. In practice, the JPA has been described as “a mechanism to disburse political patronage to a few key rebel leaders.” [1]

One of the principal armed movements in Darfur is the largely Fur-based Sudan Liberation Army of Abd al-Wahid al-Nur (SLA-AW). The group helped launch the 2003 rebel attacks on the SAF that sparked nearly two decades of war in Darfur (Darfur means “abode of the Fur”). The movement was not a signatory to the JPA and is not part of North Darfur’s Joint Protection Force. Nonetheless, General Yusuf Karjakula led a group of SLA-AW fighters from its Jabal Marra stronghold to al-Fashir in late November where they deployed to protect IDP camps from RSF assaults (Sudan Tribune, December 3). The general also met with SAF and JPF commanders, suggesting the SLA-AW may be considering joint operations to defend al-Fashir despite long-standing distrust of the SAF.

Many of the armed opposition movements have begun to split internally over the issue of alignment with the RSF or the SAF (for the rebel movements, see Terrorism Monitor, August 8). Even Minni Minawi’s faction of the SLA is experiencing divisions between its SAF-supporting leader and its military commander, General Juma Haggar, who supports the RSF (Sudan War Monitor, December 4). The Sudan Liberation Army-Transitional Council (SLA-TC), led by Al-Hadi Idris Yahya Farajallah, is considered close to the RSF, though the movement’s vice-president, Salah al-Din Abdel-Rahman al-Ma’rouf “Salah Rasas,” is considered to be a supporter of the SAF (Sudan War Monitor, December 4). A new faction of JEM under Sulayman Sandal Haggar split from the movement in August 2023 after some JEM members charged leader Jibril Ibrahim with backing the SAF (Darfur24, August 30).

Some rebel leaders are attempting to remain neutral, like Al-Tahir Abu Bakr Hajar, leader of the Gathering of Sudan Liberation Forces (GSLF), though some of his men were reported among the defenders of Nyala (Sudan War Monitor, October 26).

Foreign Intervention in the Sudan Conflict

There are allegations of foreign interference in the conflict, notably support for the RSF from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Russia’s Wagner Group, as well as Ukrainian support for General al-Burhan’s SAF.

Alleged Ukrainian Sniper on Ridge Northwest of Omdurman (Bellingcat)

Alleged Ukrainian Sniper on Ridge Northwest of Omdurman (Bellingcat)

Al-Burhan and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy met in Ireland on September 23 to discuss responses to the pro-RSF activities of the Russian Wagner Group in Sudan (Kyiv Independent, September 23; Sudan Tribune, September 23). The meeting came days after the release of videos alleged to show Ukrainian drone attacks on RSF forces in the Sudanese capital (see Eurasia Daily Monitor, November 14). Since then, videos have emerged of Ukrainian snipers operating in the hills northwest of Omdurman, as geolocated by independent investigative collective Bellingcat (Bellingcat.com, October 7). There have also been videos released on November 6, allegedly showing personnel of the Ukrainian Defense Ministry’s Main Directorate of Intelligence engaging with RSF fighters, Wagner personnel, and members of Russia’s special forces in the Sudanese city of Omdurman (Kyiv Post, November 6; Sudan War Monitor, November 10).

Journalists seeking confirmation or denial of these activities have been referred to the words of Kyrylo Budanov, the head of Ukraine’s military intelligence service HUR MOU (Holovne upravlinnja rozvidky Ministerstva oborony Ukrajiny), who stated last May that “we have killed Russians and will continue to kill Russians anywhere in the world, until the complete victory of Ukraine” (New Voice of Ukraine, May 17). RSF leader Hemetti has expressed his support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and his paramilitary force is alleged to have engaged in gold smuggling with Wagner operatives in exchange for arms and advisors.

Small operations of the type allegedly engaged in by Ukraine in Sudan ultimately have little influence on the outcome of the war. However, they do diminish the local reputation of Wagner operatives who have helped finance Russia’s war in Ukraine by smuggling gold from regions of western Sudan under RSF control.

General Yassir al-Atta (deputy to al-Burhan) stated that military intelligence and diplomatic sources had confirmed that the UAE was shipping supplies to the RSF through neighboring countries, including Chad. The allegation was denied by authorities in the UAE (Radio Tamazuj [Juba], November 29). The UAE is Sudan’s main trading partner, has been a major investor in Sudan in recent years, and is the primary destination for gold smuggled out of western Sudan. Al-Atta’s description of the UAE as a “mafia-state” led to a breakdown in diplomatic relations between the two countries (Radio Dabanga, December 11).

Atta’s remarks also incensed Chadian authorities. On December 11, they demanded an official Sudanese apology for claiming the UAE had been allowed to ship weapons and munitions to the RSF through Chad. N’Djamena promised to take “measures” if the apology did not come within three days (Sudan Tribune, December 11). Darfur governor Minni Minawi had already accused Chadian authorities of allowing the passage of arms and mercenaries through Chad to the RSF in mid-November (Radio Dabanga, November 17).

There are further allegations that the Zaghawa generals who control Chad’s powerful military are annoyed by the UAE’s support of the mainly-Arab RSF and are providing clandestine support to their Zaghawa kinsmen in JEM and the SLA-MM (Sudan Tribune, December 7).

Destruction of Khartoum

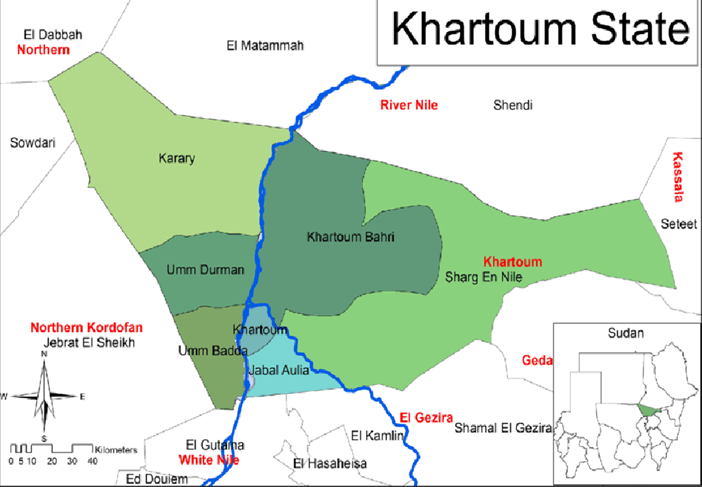

Little remains in SAF hands in Khartoum other than the much-battered army headquarters and a small patch of Khartoum North (Bahri) connected by the SAF-controlled Blue Nile rail bridge. Khartoum’s al-Jaili refinery, the largest fuel production facility in Sudan, was destroyed in a bombing on December 6, the fourth such bombing of that location since the war began. Both the RSF and the SAF accuse the other of being responsible for the destruction (Sudan Tribune, December 6). RSF posts are dispersed throughout Khartoum; in the SAF’s attempt to find and destroy them, large parts of the city have been smashed by airstrikes and artillery, including many of its most notable buildings.

The RSF now controls all of Khartoum State, with the exception of the SAF-controlled pockets in Khartoum and northern Omdurman. RSF patrols have been spotted recently in eastern Sudan, possibly preparing the way for an occupation of that region. Twenty-five miles south of Khartoum, the strategic Jabal Awliya military base and airport fell on November 20 after a siege and two-day assault, removing a major obstacle to a RSF incursion into White Nile State (Radio Dabanga, November 21).

The RSF now controls all of Khartoum State, with the exception of the SAF-controlled pockets in Khartoum and northern Omdurman. RSF patrols have been spotted recently in eastern Sudan, possibly preparing the way for an occupation of that region. Twenty-five miles south of Khartoum, the strategic Jabal Awliya military base and airport fell on November 20 after a siege and two-day assault, removing a major obstacle to a RSF incursion into White Nile State (Radio Dabanga, November 21).

Conclusion

The SAF is highly demoralized and suffers from high rates of desertion and defection. Resistance to the RSF is collapsing in many parts of the country, diminishing hopes for a negotiated settlement. There are thousands of dead, soldiers and civilians alike. The country’s GDP is expected to decline by 18 percent this year due to the war (Africa News, October 12), with over half the population in need of humanitarian assistance. Six million Sudanese are displaced and cut off from normal avenues of support. As famine approaches, the only trade activity that still works is the import and distribution of arms, despite an international embargo.

Civilian groups that had previously discovered the power of the people when overthrowing President Omar al-Bashir in 2019 have now discovered that they have zero influence in the current military power struggle. Most alarming is the emergence of patterns of ethnic and tribal violence that have ways of resisting political settlement while perpetuating grievances both new and traditional. Focused on self-enrichment, the RSF’s barely literate leadership has no rational plan for reviving the state. There is little chance that the RSF’s military success can translate into a brighter future for Sudan’s 46 million people.

Note:

[1] Amar Jamal, “Key Actors in the Juba Peace Agreement: Roles, Impacts and Lessons,” Rift Valley Institute Research Report, September 14, 2023, p.16, https://riftvalley.net/sites/default/files/publication-documents/RVI%202023.09.14%20Key%20Actors%20in%20the%20JPA.pdf